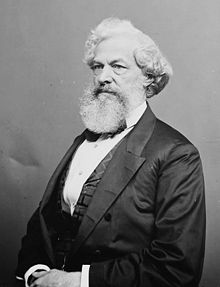

Thomas Ustick Walter

Thomas Ustick Walter | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th Architect of the Capitol | |

| In office June 11, 1851 – May 26, 1865 | |

| President | Millard Fillmore Franklin Pierce James Buchanan Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Charles Bulfinch |

| Succeeded by | Edward Clark |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 4, 1804 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | October 30, 1887 (aged 83) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Profession | Civil Engineer |

Thomas Ustick Walter | |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Moyamensing Prison Girard College |

| Projects | United States Capitol dome Philadelphia City Hall |

Thomas Ustick Walter (September 4, 1804 – October 30, 1887) was an American architect. He designed multiple buildings and institutions including Moyamensing Prison and Girard College in Philadelphia. He was the fourth Architect of the Capitol and led the addition of the north (Senate) and south (House) wings and the central dome. He was one of the founders and second president of the American Institute of Architects.

Early life and education

[edit]Born in 1804 in Philadelphia, Walter was the son of mason and bricklayer Joseph S. Walter and his wife Deborah.[1] Walter showed an aptitude for mathematics and drawing at an early age.[2] He worked as a bricklayer for his father and studied architecture in the office of William Strickland.[3]

He received an honorary Masters of Arts degree from Madison University in 1849, a Ph.D. from the University of Lewisburg in 1853, and a Doctor of Laws degree from Harvard University in 1857.[4]

Career

[edit]He established his own architectural design practice in 1830.[5] In 1831, Walter was appointed as chief architect for the design of Moyamensing Prison. In 1833, the Philadelphia City Council accepted his design for Girard College and he led construction until its completion in 1847.[5]

In 1843, he was commissioned to build a breakwater for the port of LaGuaira, Venezuela, and completed the work in 1845.[5]

The U.S. Capitol and its dome

[edit]

In 1851, Walter was selected by President Millard Fillmore for the expansion of the U.S. Capitol.[6] There were at least six draftsmen in Walter's office, headed by Walter's chief assistant, August Schoenborn, a German immigrant who had learned his profession from the ground up. It appears that he was responsible for some of the fundamental ideas in the Capitol structure. These included the curved arch ribs and an ingenious arrangement used to cantilever the base of the columns. This made it appear that the diameter of the base exceeded the actual diameter of the foundation, thereby enlarging the proportions of the total structure.[7]

Construction on the wings began in 1851 and proceeded rapidly; the House of Representatives met in its new quarters in December 1857 and the Senate occupied its new chamber by January 1859. Walter's fireproof cast iron dome was authorized by Congress on March 3, 1855, and was nearly completed by December 2, 1863, when the Statue of Freedom was placed on top. The dome's cast iron frame was supplied and constructed by the iron foundry Janes, Fowler, Kirtland & Co.[8] The thirty-six Corinthian columns designed by Walter, as well as 144 cast iron structural pillars for the dome, were supplied by the Baltimore ironworks of Poole & Hunt.[9] Walter also reconstructed the interior of the west center building for the Library of Congress after the fire of 1851. Walter continued as Capitol architect until 1865, when he resigned his position over a minor contract dispute. After 14 years in Washington, he retired to his native Philadelphia.[citation needed]

In the 1870s, financial setbacks forced Walter to come out of retirement. He worked for a year as a draftsman for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company[6] He worked as second-in-command when his friend and younger colleague John McArthur Jr., won the design competition for Philadelphia City Hall. He continued on that vast project until his death in 1887. He was interred at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.[10]

Other honors

[edit]In 1829, he was elected a member of the Franklin Institute and served in several roles including as Chairman of the Board of Managers in 1846.[11] In 1839, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[12]

For their architectural accomplishments, both Walter and Benjamin Latrobe are honored in a ceiling mosaic in the East Mosaic Corridor at the entrance to the Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress.

Walter's grandson, Thomas Ustick Walter III, was also an architect; he practiced in Birmingham, Alabama, from the 1890s to the 1910s.[13]

Works

[edit]

- Spruce Street Baptist Church, 418 Spruce St., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1829)

- Portico Row, 900–930 Spruce St., Philadelphia (1831–32)

- Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia (1832–35)[5]

- First Presbyterian Church of West Chester, West Chester, Pennsylvania (1832)[14]

- Wills Eye Hospital, Logan Square, Philadelphia (1832)[15]

- Central Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia (1833)[16]

- Founder's Hall, Girard College for Orphans, Philadelphia (1833–1848)

- Expansion of Andalusia, Bensalem Township, Pennsylvania (1833–32)[17]

- St. George's Hall, residence of Matthew Newkirk (1835)[18]

- Interior renovation of Christ Church, Philadelphia, (1835–36)[19]

- Bank of Chester County, West Chester, Pa. (1836)[20]

- West Chester Young Ladies Seminary, West Chester (1838)

- Newkirk Viaduct Monument, West Philadelphia, Philadelphia (1839)[21]

- St. James Episcopal Church, Wilmington, North Carolina (1839–40)

- Norfolk Academy Norfolk, Virginia (1840)

- Lexington Presbyterian Church, Lexington, Virginia (1843)[22]

- Breakwater, La Guaira, Venezuela (1843–45)[23]

- Chapel of the Cross, Chapel Hill, North Carolina (1843)

- Tabb Street Presbyterian Church, Petersburg, Virginia (1843)[24]

- Winder Houses, 232-34 S. 3rd St., Philadelphia (1843)[citation needed]

- Chester County Courthouse, West Chester (1846–47)[25]

- Chester County Horticultural Hall, West Chester (1848)

- Inglewood Cottage, Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia (c. 1850)

- Completion of East Wing, Old Patent Office Building, Washington, D.C. (–1853)

- West Wing, Old Patent Office Building, Washington, D.C. (1851–54, burned 1877)

- United States Capitol dome, Washington, D.C. (1855–1866)

- Preliminary design for expansion of the Treasury Building, Washington, D.C. (c. 1855)

- Expansion of the General Post Office, Washington, D.C. (1855–66)

- Marine Barracks, Pensacola, Florida (1857)

- Marine Barracks, Brooklyn, New York (1858–59)[26]

- Ingleside, Washington, D.C. (c. 1850)[27]

- Garrett-Dunn House, 7048 Germantown Ave, Mt. Airy, Philadelphia (c. 1850, burned 2009)[28][29]

- Fifth Presbyterian Church, 500 I Street N.W., Washington, D.C. (1852)[30]

- Thomas Ustick Walter House, Germantown, Philadelphia (1860–61, demolished c. 1920)[31]

- Eutaw Place Baptist Church, Baltimore, Maryland (1868–71)

It has been suggested that Walter designed the Second Empire-styled Quarters B and Quarters D at Admiral's Row in Brooklyn, New York.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]Walters was married twice. He had thirteen children, seven which outlived him.[6]

Gallery

[edit]-

Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia (1832–35, demolished 1968)

-

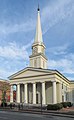

One of Walter's first commissions, the First Presbyterian Church, West Chester, Pennsylvania (1832)

-

Chester County Prison, West Chester (1838, demolished 1960)

-

Lexington Presbyterian Church, Lexington, Virginia (1843–45)

-

Chester County Courthouse, West Chester (1846–47)

-

First Baptist Church, Bristol, Pennsylvania (1851)

-

Horticultural Hall now Chester County History Center,[32] West Chester (1848)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Frary, Ihna Thayer (1940). They Built the Capitol. Ayer Publishing. p. 201.

- ^ Mason 1888, p. 322.

- ^ "Thomas Ustick Walter, Fourth Architect of the Capitol". www.aoc.gov. Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Mason 1888, p. 326.

- ^ a b c d Mason 1888, p. 323.

- ^ a b c Mason 1888, p. 325.

- ^ August Schoenborn at archINFORM

- ^ Terrell, Ellen (2015-05-20). "The Capitol Dome: Janes, Fowler, & Kirtland Co. | Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ Swett, Steven C. (2023). The metalworkers : Robert Poole, his ironworks, and technology in 19th-century America. Stephen Marchesi, Baltimore Museum of Industry. Baltimore, Maryland: Baltimore Museum of Industry. pp. 85–115. ISBN 978-0-578-28250-3. OCLC 1338040526.

- ^ "Thomas U. Walter". remembermyjourney.com. webCemeteries. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Mason 1888, pp. 326–327.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-09.

- ^ Fazio, Michael W. (2010) Landscape of Transformations: Architecture and Birmingham, Alabama. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press ISBN 978-1-57233-687-2

- ^ Filemban, Mustafa. "WC History: The Shipwrecked Entrepreneur". www.downtownwestchester.com. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ Tasman, William (1980). The History of Wills Eye Hospital. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0061425318.

- ^ "Central Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia [graphic]". Library Company of Philadelphia Digital Collections. March 1861. Retrieved 2023-11-02.

- ^ Moss, Roger W. (1998-05-29). Historic Houses of Philadelphia: A Tour of the Region's Museum Homes. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-8122-3438-1.

- ^ "St. George's Hall. [graphic]". The Library Company of Philadelphia. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ^ Building & Furnishing of Christ Church Philadelphia. Christ Church Philadelphia. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4223-6535-9.

- ^ "Bank of Chester County, 17 North High Street, West Chester, Chester County, PA" (Searchable database). Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey, Engineering Record, Landscapes Survey Collection. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- ^ "Newkirk Monument". www.philadelphiabuildings.org. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (March 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Lexington Presbyterian Church" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ^ Crichfield, George Washington (1908). Foreigners in Latin America and relations with foreign governments. Brentano's. p. 304.

- ^ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (February 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Tabb Street Presbyterian Church" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- ^ dsf.chesco.org Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine - Chester county courthouse West Chester, Pennsylvania

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (2015-02-26). The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. OUP Oxford. p. 822. ISBN 978-0-19-105385-6.

- ^ "Ingleside (Stoddard Baptist Home) - Originally designed by Thomas Ustick Walter, this house is an important example of his domestic design". DC Historic Sites. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ^ "Garrett-Dunn House destroyed". WHYY. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ^ Caparella, Kitty (3 August 2009). "Garrett-Dunn House, a landmark in Mt. Airy, destroyed in fire". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ^ Pressley Montes, Sue Anne (28 August 2007). "Church's Face-Lift Plans Uncover Ties to U.S. Capitol Architect". The Washington Post.

- ^ Harrison, Stephen G. (1992). "Documenting a Design: The Thomas Ustick Walter House, 1861-1866, Germantown, Pennsylvania". University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Lukens, Ph.D., Rob (December 11, 2011). "THOMAS U. WHO???". www.chestercohistorical.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-20. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

Sources

- Mason, George C., Jr. (1888). "Biographical Notice of Thomas Ustick Walter A.M., Ph.D., LL.D., Late Member of the American Philosophical Society". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society Held at Philadelphia for Promoting Useful Knowledge. XXV: 322–327.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Aoc.gov file

- Brief biography of Thomas Ustick Walter

- Walter's drawings at the Atheneum of Philadelphia

- The Winterthur Library Overview of an archival collection on Thomas Ustick Walter.

- Library of Congress, Jefferson Building East Corridor mosaics

- Old Patent Office Building video

- 1804 births

- 1887 deaths

- 19th-century American architects

- Architects from Philadelphia

- Architects of the United States Capitol

- American neoclassical architects

- American people of German descent

- Bucknell University alumni

- Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia)

- Fellows of the American Institute of Architects

- Greek Revival architects

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Presidents of the American Institute of Architects

![Horticultural Hall now Chester County History Center,[32] West Chester (1848)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Historic_American_Buildings_Survey%2C_PHOTOCOPY_1870%27S._-_Chester_County_Horticultural_Hall%2C_225_North_High_Street%2C_West_Chester%2C_Chester_County%2C_PA_HABS_PA%2C15-WCHES%2C4-4.tif/lossy-page1-120px-thumbnail.tif.jpg)