Generations of Noah

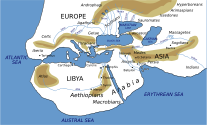

The Generations of Noah, also called the Table of Nations or Origines Gentium,[1] is a genealogy of the sons of Noah, according to the Hebrew Bible (Genesis 10:9), and their dispersion into many lands after the Flood,[2] focusing on the major known societies. The term 'nations' to describe the descendants is a standard English translation of the Hebrew word "goyim", following the c. 400 CE Latin Vulgate's "nationes", and does not have the same political connotations that the word entails today.[3]

The list of 70 names introduces for the first time several well-known ethnonyms and toponyms important to biblical geography,[4] such as Noah's three sons Shem, Ham, and Japheth, from which 18th-century German scholars at the Göttingen school of history derived the race terminology Semites, Hamites, and Japhetites. Certain of Noah's grandsons were also used for names of peoples: from Elam, Ashur, Aram, Cush, and Canaan were derived respectively the Elamites, Assyrians, Arameans, Cushites, and Canaanites. Likewise, from the sons of Canaan: Heth, Jebus, and Amorus were derived Hittites, Jebusites, and Amorites. Further descendants of Noah include Eber (from Shem), the hunter-king Nimrod (from Cush), and the Philistines (from Misrayim).

As Christianity spread across the Roman Empire, it carried the idea that all people were descended from Noah. Not all Near Eastern people were covered in the biblical genealogy (Iranic peoples such as Persians, Indic people such as Mitanni, and also others such as Greeks, Kassites, Sumerians and Hurrians are missing), as well as the Northern European and Western European peoples important to the Late Roman and Medieval world, such as the Celtic, Slavic, Germanic, and Nordic peoples; nor were others of the world's peoples, such as sub-Saharan Africans, Native Americans, Turkic and Iranic peoples of Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Far East, and Australasia. Scholars later derived a variety of arrangements to make the table fit, with for example the addition of Scythians, which do feature in the tradition, being claimed as the ancestors of much of Northern Europe.[5]

According to the biblical scholar Joseph Blenkinsopp, the 70 names in the list express symbolically the unity of humanity, corresponding to the 70 descendants of Israel who go down into Egypt with Jacob at Genesis 46:27 and the 70 elders of Israel who visit God with Moses at the covenant ceremony in Exodus 24:1–9.[6]

Table of Nations

[edit]On the family pedigrees contained in the biblical pericope of Noah, Saadia Gaon (882‒942) wrote:

The Scriptures have traced the patronymic lineage of the seventy nations to the three sons of Noah, as also the lineage of Abraham and Ishmael, and of Jacob and Esau. The blessed Creator knew that men would find solace at knowing these family pedigrees, since our soul demands of us to know them, so that [all of] mankind will be held in fondness by us, as a tree that has been planted by God in the earth, whose branches have spread out and dispersed eastward and westward, northward and southward, in the habitable part of the earth. It also has the dual function of allowing us to see the multitude as a single individual, and the single individual as a multitude. Along with this, man ought to contemplate also on the names of the countries and of the cities [wherein they settled]."[7]

Maimonides, echoing the same sentiments, wrote that the genealogy of the nations contained in the Law has the unique function of establishing a principle of faith, how that, although from Adam to Moses there was no more than a span of two-thousand five hundred years, and the human race was already spread over all parts of the earth in different families and with different languages, they were still people having a common ancestor and place of beginning.[8]

Other Bible commentators observe that the Table of Nations is unique compared to other genealogies since it depicts a "broad network of cousins", with a "shallow chain of brotherly relationships". Meanwhile, the other genealogies focus on "narrow chains of father-son relationships".[9]

Book of Genesis

[edit]

Chapters 1–11 of the Book of Genesis are structured around five toledot statements ("these are the generations of..."), of which the "generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth" is the fourth. Events before the Genesis flood narrative, the central toledot, correspond to those after: the post-Flood world is a new creation corresponding to the Genesis creation narrative, and Noah had three sons who populated the world. The correspondences extend forward as well: there are 70 names in the Table, corresponding to the 70 Israelites who go down into Egypt at the end of Genesis and to the 70 elders of Israel who go up the mountain at Sinai to meet with God in Exodus. The symbolic force of these numbers is underscored by the way the names are frequently arranged in groups of seven, suggesting that the Table is a symbolic means of implying universal moral obligation.[10] The number 70 also parallels Canaanite mythology, where 70 represents the number of gods in the divine clan who are each assigned a subject people, and where the supreme god El and his consort, Asherah, has the title "Mother/Father of 70 gods", which, due to the coming of monotheism, had to be changed, but its symbolism lived on in the new religion.[citation needed]

The overall structure of the Table is:

- 1. Introductory formula, v.1

- 2. Japheth, vv.2–5

- 3. Ham, vv.6–20

- 4. Shem, vv.21–31

- 5. Concluding formula, v.32.[11]

The overall principle governing the assignment of various peoples within the Table is difficult to discern: it purports to describe all humankind, but in reality restricts itself to the Egyptian lands of the south, the Mesopotamian lands, and Anatolia/Asia Minor and the Ionian Greeks, and in addition, the "sons of Noah" are not organized by geography, language family or ethnic groups within these regions.[12] The Table contains several difficulties: for example, the names Sheba and Havilah are listed twice, first as descendants of Cush the son of Ham (verse 7), and then as sons of Joktan, the great-grandsons of Shem, and while the Cushites are North African in verses 6–7 they are unrelated Mesopotamians in verses 10–14.[13]

The date of composition of Genesis 1–11 cannot be fixed with any precision, although it seems likely that an early brief nucleus was later expanded with extra data.[14] Portions of the Table itself 'may' derive from the 10th century BCE, while others reflect the 7th century BCE and priestly revisions in the 5th century BCE.[2] Its combination of world review, myth and genealogy corresponds to the work of the Greek historian Hecataeus of Miletus, active c. 520 BCE.[15]

Book of Chronicles

[edit]I Chronicles 1 includes a version of the Table of Nations from Genesis, but edited to make clearer that the intention is to establish the background for Israel. This is done by condensing various branches to focus on the story of Abraham and his offspring. Most notably, it omits Genesis 10:9–14, in which Nimrod, a son of Cush, is linked to various cities in Mesopotamia, thus removing from Cush any Mesopotamian connection. In addition, Nimrod does not appear in any of the numerous Mesopotamian King Lists.[16]

Book of Jubilees

[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2015) |

The Table of Nations is expanded upon in detail in chapters 8–9 of the Book of Jubilees, sometimes known as the "Lesser Genesis," a work from the early Second Temple period.[17] Jubilees is considered pseudepigraphical by most Christian and Jewish denominations but thought to have been held in regard by many of the Church Fathers.[18] Its division of the descendants throughout the world are thought to have been heavily influenced by the "Ionian world map" described in the Histories of Herodotus,[19] and the anomalous treatment of Canaan and Madai are thought to have been "propaganda for the territorial expansion of the Hasmonean state".[20]

Septuagint version

[edit]The Hebrew bible was translated into Greek in Alexandria at the request of Ptolemy II, who reigned over Egypt 285–246 BCE.[21] Its version of the Table of Nations is substantially the same as that in the Hebrew text, but with the following differences:

- It lists Elisa as an extra son of Japheth, giving him eight instead of seven, while continuing to list him also as a son of Javan, as in the Masoretic text.

- Whereas the Hebrew text lists Shelah as the son of Arpachshad in the line of Shem, the Septuagint has a Cainan as the son of Arpachshad and father of Shelah – the Book of Jubilees gives considerable scope to this figure. Cainan appears again at the end of the list of the sons of Shem.

- Obal, Joktan's eighth son in the Masoretic text, does not appear.[22]

1 Peter

[edit]In the First Epistle of Peter, 3:20, the author says that eight righteous persons were saved from the Great Flood, referring to the four named males, and their wives aboard Noah's Ark not enumerated elsewhere in the Bible.

Sons of Noah: Shem, Ham and Japheth

[edit]

The Genesis flood narrative tells how Noah and his three sons Shem, Ham, and Japheth, together with their wives, were saved from the Deluge to repopulate the Earth.

- Shem's descendants: Genesis chapter 10 verses 21–30 gives one list of descendants of Shem. In chapter 11 verses 10–26 a second list of descendants of Shem names Abraham and thus the Arabs and Israelites.[23] In the view of some 17th-century European scholars (e.g., John Webb), the Native American peoples of North and South America, eastern Persia and "the Indias" descended from Shem,[24] possibly through his descendant Joktan.[25][26] Some modern creationists identify Shem as the progenitor of Y-chromosomal haplogroup IJ, and hence haplogroups I (common in northern Europe) and J (common in the Middle East).[27]

- Ham's descendants: The forefather of Cush, Egypt, and Put, and of Canaan, whose lands include portions of Africa. The Aboriginal Australians and indigenous people of New Guinea have also been tied to Ham.[28][29] The etymology of his name is uncertain; some scholars have linked it to terms connected with divinity, but a divine or semi-divine status for Ham is unlikely.[30]

- Japheth's descendants: His name is associated with the mythological Greek Titan Iapetus, and his sons include Javan, the Greek-speaking cities of Ionia.[31] In Genesis 9:27 it forms a pun with the Hebrew root yph: "May God make room [the hiphil of the yph root] for Japheth, that he may live in Shem's tents and Canaan may be his slave."[32]

Based on an old Jewish tradition contained in the Aramaic Targum of pseudo-Jonathan ben Uzziel,[33] an anecdotal reference to the Origines gentium in Genesis 10:2–ff has been passed down, and which, in one form or another, has also been relayed by Josephus in his Antiquities,[34] repeated in the Talmud,[35] and further elaborated by medieval Jewish scholars, such as in works written by Saadia Gaon,[36] Josippon,[37] and Don Isaac Abarbanel,[38] who, based on their own knowledge of the nations, showed their migratory patterns at the time of their compositions:

"The sons of Japheth are Gomer,[39] and Magog,[40] and Madai,[41][42] and Javan,[43] and Tuval,[44] and Meshech[45] and Tiras,[46] while the names of their diocese are Africa proper,[a] and Germania,[47] and Media, and Macedonia, and Bithynia,[48] and Moesia (var. Mysia) and Thrace. Now, the sons of Gomer were Ashkenaz,[49] and Rifath[50] and Togarmah,[51][52] while the names of their diocese are Asia,[53] and Parthia and the 'land of the barbarians.' The sons of Javan were Elisha,[b] and Tarshish,[c] Kitim[54] and Dodanim,[55] while the names of their diocese are Elis,[56] and Tarsus, Achaia[57] and Dardania." ---Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Genesis 10:2–5

"The sons of Ḥam are Kūš, and Miṣrayim,[58] and Fūṭ (Phut),[59] and Kenaʻan,[60] while the names of their diocese are Arabia, and Egypt, and Elīḥerūq[61] and Canaan. The sons of Kūš are Sebā[62] and Ḥawīlah[63] and Savtah[64] and Raʻamah and Savteḫā,[65] [while the sons of Raʻamah are Ševā and Dedan].[66] The names of their diocese are called Sīnīrae,[d] and Hīndīqī,[e] Samarae,[f] Lūbae,[67] Zinğae,[g] while the sons of Mauretinos[h] are [the inhabitants of] Zemarğad and [the inhabitants of] Mezağ."[68] ---Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Genesis 10:6–7

"The sons of Shem are Elam,[69] and Ashur,[70] and Arphaxad,[71] and Lud,[72] and Aram.[73] [And the children of Aram are these: Uz,[74] and Hul,[75] and Gether,[76] and Mash.[77]] Now, Arphaxad begat Shelah (Salah), and Shelah begat Eber.[78] Unto Eber were born two sons, the one named Peleg,[79] since in his days the [nations of the] earth were divided, while the name of his brother is Joktan.[80] Joktan begat Almodad, who measured the earth with ropes;[81] Sheleph, who drew out the waters of rivers;[82] and Hazarmaveth,[83] and Jerah,[84] and Hadoram,[85] and Uzal,[86] and Diklah,[87] and Obal,[88] and Abimael,[89] and Sheba,[85][i] and Ophir,[j] and Havilah,[90] and Jobab,[91] all of whom are the sons of Joktan."[92] ---Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Genesis 10: 22–28

| Noahic descendant (Gen. 10:2 – 10:29) | Proposed historical identifications |

|---|---|

| Gomer | Cimmerians[93][94] |

| Magog | Lydia (Mermnad dynasty)[95] |

| Madai | Generally reckoned as the Medes,[96][97] but other proposals include Matiene, Mannaea, and Mitanni.[98] |

| Javan | Ionians[99] |

| Tubal | Tabal[100][101] |

| Tiras | Uncertain, proposals include Troy, Thrace and the Sea Peoples known as the Teresh.[97][102] |

| Meshech | Muski[100] |

| Ashkenaz | Scythians[97] |

| Riphath | Uncertain, proposals include Paphlagonia, and the semihistorical Arimaspi.[103] |

| Togarmah | Tegarama[100] |

| Elishah | Uncertain, usually reckoned as Alashiya,[104][105] but other proposals include Magna Graecia, the Sicels,[106] the Aeolians[102] and Carthage.[107] |

| Tarshish | Tarshish, though its location has been debated for centuries and remains uncertain. |

| Kittim | Kition[102] |

| Dodanim | Uncertain, further complicated by its later attestation as Rodanim. Those assuming Dodanim represents the original form have proposed Dodona,[108][109] Dardania,[108] and Dardanus;[110] whereas those assuming Rodanim represents the original have almost universally proposed Rhodes.[103][109] |

| Cush | Kush[111] |

| Mizraim | Egypt[112] |

| Put | Ancient Libya[113] |

| Canaan | Canaan[112] |

| Seba | Sabaeans (eastern Ethiopia)[112] |

| Havilah | Uncertain, probably Ḫawlan, a region in southern Arabia.[112][114] |

| Sabtah | Uncertain, possibly Šabwat[112] |

| Raamah | Uncertain, possibly Ragmatum, an ancient city in southwest Arabia.[112] |

| Sabtecha | Uncertain, possibly Shabakat, an ancient city in Hadhramaut.[112] |

| Sheba | Sabaʾ[115][116][117] |

| Dedan | Lihyan[118] |

| Nimrod | Uncertain, various proposals exist imagining Nimrod as an ethnic group, person, city, and deity. |

| Ludim | Lydia,[119] sometimes amended to read Lubim (Libya)[120] |

| Anamim | Uncertain |

| Lehabim | Uncertain, sometimes suggested to represent Libya.[121] |

| Naphtuhim | Uncertain, possibly Memphis, or Lower Egypt as a whole.[121] |

| Pathrusim | Pathros[121] |

| "the Casluhites" | Kasluḥet of Egypt, modern identification uncertain.[122] |

| "the Caphtorites" | Caphtor, modern identification uncertain, proposals include Cilicia, Cyprus, and Crete.[123] |

| Sidon | Sidon[124] |

| Heth | Biblical Hittites |

| "the Jebusites" | Jebusites, traditionally identified as an ethnic people dwelling in Jerusalem.[124] |

| "the Amorites" | Amorites[124] |

| "the Girgashites" | Possibly Karkisa.[125] |

| "the Hivites" | Hivites, traditionally identified as a Canaanite people dwelling in northern Israel.[124] |

| "the Arkites" | Arqa[124] |

| "the Sinites" | Siyannu[124] |

| "the Arvadites" | Arwad[126] |

| "the Zemarites" | Sumur[126] |

| "the Hamathites" | Hama[126] |

| Elam | Elam[96] |

| Ashur | Assyria[96][127] |

| Arpachshad | Uncertain, possibly Chaldea[127] |

| Lud | Lydia[127] |

| Aram | Aram[128] |

| Uz | "Land of Uz", hypothesized locations include Aram and Edom.[128] |

| Hul | Uncertain, possibly Houla[128] |

| Gether | Uncertain, sometimes suggested to represent Geshur.[129][128] |

| Mash | Uncertain, sometimes equated with Massa,[129] Meshech[128] or Maacah (Genesis 22:24).[130] |

| Selah | Uncertain |

| Eber | Hebrews[131][132] |

| Peleg | Uncertain, possibly Palgu, a site at the junction of the Khabur and Euphrates rivers.[132] |

| Joktan | Uncertain, perhaps related to the Qahtanites.[132] |

| Almodad | Uncertain |

| Sheleph | A South Arabian tribe referred to by Arab geographers as as-Salif or as-Sulaf.[133] |

| Hazarmaveth | Hadhramaut[133] |

| Jerah | Uncertain, possibly related to the place name WRḪN mentioned in a Sabean inscription.[133] |

| Hadoram | Uncertain, possibly related to the place name DWRN mentioned in Sabean inscriptions.[133] |

| Uzal | Uncertain, probably related to the place name ʾAzal, designating two different sites in South Arabia.[133] |

| Diklah | Uncertain, probably related to the place name NḪL ḪRF, in the region of Sirwah.[133] |

| Obal | Uncertain, probably related to the tribe BNW ʿBLM ("sons of ʿAbil"), mentioned in Sabean inscriptions and probably settled in the Yemeni highlands.[133] |

| Abimael | Uncertain, it may be related to the tribe ʾBM ṮTR mentioned in Sabean inscriptions.[133] |

| Ophir | Uncertain, proposals include the Farasan Islands,[134] Sumatra, Sri Lanka, Poovar,[135][136][137] numerous locations in Africa, Mahd adh Dhahab,[138] and Zafar.[133] |

| Jobab | Uncertain, probably related to the Sabaean tribe YHYBB (*Yuhaybab), mentioned in Old South Arabian inscriptions.[139] |

Problems with identification

[edit]Because of the traditional grouping of people based on their alleged descent from the three major biblical progenitors (Shem, Ham, and Japheth) by the three Abrahamic religions, in former years there was an attempt to classify these family groups and to divide humankind into three races called Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and Negroid (originally named "Ethiopian"), terms which were introduced in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen school of history.[140] It is now recognized that determining precise descent-groups based strictly on patrilineal descent is problematic, as nations are not stationary. People are often multi-lingual and multi-ethnic, and people sometimes migrate from one country to another[141] - whether voluntarily or involuntarily. Some nations have intermingled with other nations and can no longer trace their paternal descent,[142] or have assimilated and abandoned their mother's tongue for another language. In addition, phenotypes cannot always be used to determine one's ethnicity because of interracial marriages. A nation today is defined as "a large aggregate of people inhabiting a particular territory united by a common descent, history, culture, or language." The biblical line of descent is irrespective of language,[143] place of nativity,[144] or cultural influences, as all that is binding is one's patrilineal line of descent.[145] For these reasons, attempting to determine precise blood relation of any one group in today's Modern Age may prove futile. Sometimes people sharing a common patrilineal descent spoke two separate languages, whereas, at other times, a language spoken by a people of common descent may have been learnt and spoken by multiple other nations of different descent.

Another problem associated with determining precise descent-groups based strictly on patrilineal descent is the realization that, for some of the prototypical family groups, certain sub-groups have sprung forth, and are considered diverse from each other (such as Ismael, the progenitor of the Arab nations, and Isaac, the progenitor of the Israelite nation, although both family groups are derived from Shem's patrilineal line through Eber. The total number of other sub-groups, or splinter groups, each with its distinct language and culture is unknown.

Ethnological interpretations

[edit]Identifying geographically-defined groups of people in terms of their biblical lineage, based on the Generations of Noah, has been common since antiquity.

The early modern biblical division of the world's "races" into Semites, Hamites and Japhetites was coined at the Göttingen school of history in the late 18th century – in parallel with the color terminology for race which divided mankind into five colored races ("Caucasian or White", "Mongolian or Yellow", "Aethiopian or Black", "American or Red" and "Malayan or Brown").

Extrabiblical sons of Noah

[edit]There exist various traditions in post-biblical and talmudic sources claiming that Noah had children other than Shem, Ham, and Japheth who were born before the Deluge.

According to the Quran (Hud 42–43), Noah had another unnamed son who refused to come aboard the Ark, instead preferring to climb a mountain, where he drowned. Some later Islamic commentators give his name as either Yam or Kan'an.[146]

According to Irish mythology, as found in the Annals of the Four Masters and elsewhere, Noah had another son named Bith who was not allowed aboard the Ark, and who attempted to colonise Ireland with 54 persons, only to be wiped out in the Deluge.[citation needed]

Some 9th-century manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle assert that Sceafa was the fourth son of Noah, born aboard the Ark, from whom the House of Wessex traced their ancestry; in William of Malmesbury's version of this genealogy (c. 1120), Sceaf is instead made a descendant of Strephius, the fourth son born aboard the Ark (Gesta Regnum Anglorum).[citation needed]

An early Arabic work known as Kitab al-Magall "Book of Rolls" (part of Clementine literature) mentions Bouniter, the fourth son of Noah, born after the flood, who allegedly invented astronomy and instructed Nimrod.[147] Variants of this story with often similar names for Noah's fourth son are also found in the c. fifth century Ge'ez work Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan (Barvin), the c. sixth century Syriac book Cave of Treasures (Yonton), the seventh century Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius (Ionitus[148]), the Syriac Book of the Bee 1221 (Yônatôn), the Hebrew Chronicles of Jerahmeel, c. 12th–14th century (Jonithes), and throughout Armenian apocryphal literature, where he is usually referred to as Maniton; as well as in works by Petrus Comestor c. 1160 (Jonithus), Godfrey of Viterbo 1185 (Ihonitus), Michael the Syrian 1196 (Maniton), Abu al-Makarim c. 1208 (Abu Naiţur); Jacob van Maerlant c. 1270 (Jonitus), and Abraham Zacuto 1504 (Yoniko).

Martin of Opava (c. 1250), later versions of the Mirabilia Urbis Romae, and the Chronica Boemorum of Giovanni de' Marignolli (1355) make Janus (the Roman deity) the fourth son of Noah, who moved to Italy, invented astrology, and instructed Nimrod.[citation needed]

According to the monk Annio da Viterbo (1498), the Hellenistic Babylonian writer Berossus had mentioned 30 children born to Noah after the Deluge, including Macrus, Iapetus Iunior (Iapetus the Younger), Prometheus Priscus (Prometheus the Elder), Tuyscon Gygas (Tuyscon the Giant), Crana, Cranus, Granaus, 17 Tytanes (Titans), Araxa Prisca (Araxa the Elder), Regina, Pandora Iunior (Pandora the Younger), Thetis, Oceanus, and Typhoeus. However, Annio's manuscript is widely regarded today as having been a forgery.[149]

Historian William Whiston stated in his book A New Theory of the Earth that Noah, who is to be identified with Fuxi, migrated with his wife and children born after the deluge to China, and founded Chinese civilization.[150][151]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The sense here is to Africa Zeugitana in the north; Africa Byzacena to its adjacent south (corresponding to eastern Tunisia), and Africa Tripolitania to its adjacent south (corresponding to southern Tunisia and northwest Libya). All of which were part of the Dioecesis Africae, or Africa propria, in early Roman times. See Leo Africanus (1974), vol. 1, p. 22. Neubauer (1868:400) thought that Afriki in the Aramaic text "should necessarily represent a country in Asia here. Some scholars want to see Phrygia there, others Iberia" (End Quote).

- ^ A name typically associated with the Aeolians, who settled in Ilida (formerly known as Elis) in Greece, and in the regions thereabout. Jonathan ben Uzziel, who rendered an Aramaic translation of the Book of Ezekiel in the early 1st-century CE, wrote that Elisha in Ezekiel 27:7 is the province of Italy, suggesting that his descendants had originally settled there. According to Hebrew Bible exegete, Abarbanel (1960:173), they also established a large colony in Sicily, whose inhabitants are known as Sicilians. According to Josippon (1971:1), Elisha's descendants had also settled in Germany (Almania).

- ^ According to Abarbanel (1960:173), the descendants of Tarshish eventually settled in Tuscany and in Lombardy, and made-up parts of the populations of Florence, Milan, and Venice, underscoring the fact that the migration of man and of different ethnic groups is always fluid and ever changing.

- ^ A place thought to be in present-day Sudan.[citation needed]

- ^ A place on the sub-continent of India.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, describes this place as being situate along the banks of the Nile River.

- ^ The medieval Arab geographers gave the name Zinğ or Zinj to the African people who dwell along the Indian Ocean, such as in present-day Kenya, but may also refer to places along the Swahili Coast. See Ibn Khaldun (1927:106), who writes in the 14th-century of the Zinğ on this wise: "Ibn-Said enumerates nineteen peoples or tribes of which the black race is made up; Thus, on the East side, on the Indian Ocean, we find the Zendj (sic), a nation which owns the city of Monbeça (Mombasa) and practices idolatry" (End Quote). Ibn Khaldun (1967), p. 123, repeats the same in his work, The Muqaddimah, placing the people who are called Zinğ along the coast of the Indian Ocean, between Zeila and Mogadishu.

- ^ Mauretinos was the forebear of the Black Moors, from whom the region in North Africa bears its name. His name is generally associated with the biblical Raʻamah, and whose posterity were called Maurusii by the Greeks. In Tangier (the 1st Mauretania), the Black Moors were already a minority race at the time of Pliny, largely supplanted by the Gaetulians. According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32), the descendants of Raʻamah (Mauretinos) were thought to have settled Kakaw, possibly Gao, along the bend of the Niger River. Alternatively, Saadia Gaon may have been referring to the Gaoga who inhabit a region bordering on Borno to the west and Nubia to the east. On this place, see Leo Africanus (1974: vol. 3, p. 852 - note 27)

- ^ Pliny, in his Natural History, mentions this place under the name Sabaei.

- ^ In Jewish tradition, Ophir is often associated with a place in India, where the descendants of Ophir are thought to have settled. Fourteenth-century biblical commentator, Nathanel ben Isaiah, writes: "And Ophir, and Havilah, and Jobab (Gen. 10:29), these are the tracts of countries in the east, being those of the first clime" (End Quote), and which first clime, according to al-Biruni, the sub-continent of India falls entirely therein. Cf. Josephus, (Antiquities of the Jews 8.6.4., s.v. Aurea Chersonesus). The 10th-century lexicographer, Ben Abraham al-Fasi (1936:46), identified Ophir with Serendip, the old Persian name for Sri Lanka (aka Ceylon).

References

[edit]- ^ Reynolds, Susan (October 1983). "Medieval Origines Gentium and the Community of the Realm". History. 68 (224). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell: 375–390. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1983.tb02193.x. JSTOR 24417596.

- ^ a b Rogers 2000, p. 1271.

- ^ Zernatto, Guido; Mistretta, Alfonso G. (July 1944). "Nation: The History of a Word". The Review of Politics. 6 (3). Cambridge University Press: 351–366. doi:10.1017/s0034670500021331 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 1748-6858. JSTOR 1404386. S2CID 143142650.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Biblical Geography," Catholic Encyclopedia: "The ethnographical list in Genesis 10 is a valuable contribution to the knowledge of the old general geography of the East, and its importance can scarcely be overestimated."

- ^ Johnson, James William (April 1959). "The Scythian: His Rise and Fall". Journal of the History of Ideas. 20 (2). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press: 250–257. doi:10.2307/2707822. JSTOR 2707822.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 156.

- ^ Saadia Gaon 1984b, p. 180.

- ^ Ben Maimon 1956, p. 381 (part 3, ch. 50).

- ^ "Genesis chapter 10 ESV Commentary". BibleRef.com. 2024. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, pp. 4 and 155–156.

- ^ Towner 2001, p. 102.

- ^ Gmirkin 2006, p. 140–141.

- ^ Towner 2001, p. 101–102.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 156–157.

- ^ Brodie 2001, p. 186.

- ^ Sadler 2009, p. 123.

- ^ Scott 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Ruiten 2000, p. 1.

- ^ Machiela 2009, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Alexander 1988, p. 102–103.

- ^ Pietersma & Wright 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ Scott 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Strawn 2000a, p. 1205.

- ^ Mungello, David E. (1989). Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 179, 336–337. ISBN 0-8248-1219-0.

there are more references in that book on the early Jesuits' and others' opinions on Noah's Connection to China

- ^ "History Collection - Collection - UWDC - UW-Madison Libraries". search.library.wisc.edu. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ Shalev, Zur (2003). "Sacred Geography, Antiquarianism and Visual Erudition: Benito Arias Montano and the Maps in the Antwerp Polyglot Bible" (PDF). Imago Mundi. 55: 71. doi:10.1080/0308569032000097495. S2CID 51804916. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2017-01-17.

- ^ http://aschmann.net/BibleChronology/Genesis10.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "1770s–1840s: early ideas – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/154991623/Carey_Fraser_240117a.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Strawn 2000b, p. 543.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 158.

- ^ Thompson 2014, p. 102.

- ^ Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (1974)

- ^ Josephus 1998, pp. 1.6.1-4.

- ^ Jerusalem Talmud, Megillah 1:9 [10a]; Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 10a

- ^ Saadia Gaon 1984, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Josippon 1971, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Abarbanel 1960, pp. 173–174.

- ^ According to Josephus, Gomer's descendants settled in Galatia. According to Sozomen; Philostorgius (1855), pp. 431–432, "Upper Galatia and the district lying around the Alps were later called Gallia, or Gaul by the Romans." Cf. Babylonian Talmud (Yoma 10a) where it associates Gomer with the land of Germania. According to 2nd-century author, Aretaeus of Cappadocia, the Celts were thought to be an offshoot of the Gauls.

- ^ His progeny were initially called by the Greeks "Scythians" (Herodotus, Book IV. 3–7; pp. 203–207), a people that originally inhabited those lands stretching between the Black and Aral Seas (S.E. Europe and Asia), although some of which people later went as far eastward as the Altai Mountains. Abarbanel (1960:173) alleges that Magog was also the progenitor of the Goths, a Germanic race. The Goths have a history of migration where they are known to have settled among other nations, such as among the inhabitants of Italy and of France and of Spain. See Isidore of Seville (1970:3). The Jerusalem Talmud, Leiden MS. (Megillah 1:9 [10a]) uses the word Getae to describe the descendants of Magog. According to Isidore of Seville (2006:197), the Dacians (the ancient people inhabiting Romania - formerly Thrace) were offshoots of the Goths.

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1.), Madai's posterity inhabited the country of the Medes, the capital city of which, according to Herodotus, was Ecbatana.

- ^ Herodotus (1971). E.H. Warmington (ed.). Herodotus: The Persian Wars. Vol. 3 (Books V–VII). Translated by A.D. Godley. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; William Heinemann Ltd. p. 377 (Book VII). ISBN 0-674-99133-8.

The Medes were in old time called by all men Arians (Aryan)

(ISBN 0-434-99119-8 - British) - ^ According to Josippon (1971:1), the descendants of Javan inhabited Macedonia. According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1.), from Javan were derived the Ionians and all the Grecians.

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1), the descendants of Tuval settled in the Iberian Peninsula. Abarbanel (1960:173), citing Josippon, concurs with this view, who adds that, besides Spain, some of his descendants had also settled in Pisa (of Italy), as well as in France along the River Seine, and in Britain. The Jerusalem Talmud (Megillah 10a), following the Aramaic Targum, ascribes the descendants of Tuval to the region of Bithynia. Alternatively, Josephus may have been referring to the Caucasian Iberians, the ancestors of modern Georgians.

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1), Meshech was the father of the indigenous peoples of Cappadocia in Central Anatolia, Turkey, where they had built the city Mazaca. This view is followed by Abarbanel (1960:173), although he seemed to confound Cappadocia with another place by the same name in Greater Armenia, near the Euphrates River. R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32 - note 5) opined that the descendants of Meshech had also settled in Khorasan. The Jerusalem Talmud (Megillah 10a), following the Aramaic Targum, ascribes the descendants of Meshech to the region of Moesia.

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1) and the Jerusalem Talmud (Megillah 10a), the descendants of Tiras are said to have originally settled in the country of Thrace (Thracians). In the Babylonian Talmud (Yoma 10a), one rabbi holds that some of his descendants settled in Persia, a view held also by R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32). According to Josippon (1971:1), Tiras was the ancestor of the Russian people (perhaps Kievan Rus'), as well as of those peoples who first settled in Bosnia, and in England (perhaps referring to the ancient Britons, the Picts, and the Scots – a Celtic race). This opinion seems to be followed by Abarbanel (1960:173) who wrote that Tiras was the ancestor of the Russian people and of the native peoples of England. As for the early Britons and Picts, according to The Saxon Chronicles, they were joined by the Angles and Jutes (Denmark) from the Old Saxons. The Jutes had established colonies in Kent and Wight, whilst the Angles had established colonies in Mercia and in all the Northumbria in about 449 CE.

- ^ Historians and anthropologists note that the entire region east of the Rhine River was known by the Romans as Germania (Germany), or what is transcribed in some sources as Germani, Germanica. The region, though now settled by a multitude of mixed peoples, was resettled some 4,500 years ago (based on a study presented in 2013 by Professor Alan J. Cooper, from the Australian Center for Ancient DNA, and by fellow co-worker Dr. Wolfgang Haak, who carried out research on early Neolithic skeletons discovered during an excavation in Sweden, and published in the article, "Ancient Europeans Mysteriously Vanished 4,500 Years Ago"); being resettled by a group of peoples comprising the Germanic Tribes, which group is largely thought to include the Goths, whether Ostrogoths or Visigoths, the Vandals and the Franks, Burgundians, Alans, Langobards, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Suebi and Alamanni.

- ^ According to Pausanias, in his Description of Greece (on Arcadia 8.9.7.), "the Bithynians are by descent Arcadians of Mantineia," that is to say, Grecians by origin; the descendants of Javan.

- ^ Considered by many to be the progenitor of the ancient Gauls (the people of Gallia, meaning, from Austria, France and Belgium, although this view is not conclusive. According to Saadia Gaon's Tafsir (a Judeo-Arabic translation of the Pentateuch), Ashkenaz was the progenitor of the Slavic peoples (Slovenes, etc.). According to Gedaliah ibn Jechia's seminal work, Shalshelet Ha-Kabbalah (p. 219), who cites in the name of Sefer Yuchasin, the descendants of Ashkenaz had also originally settled in what was then called Bohemia, which today is the present-day Czech Republic. This view is corroborated by native Czech historian and chronicler Dovid Solomon Ganz (1541–1613), author of a book published in Hebrew, entitled Tzemach Dovid (Part II, p. 71; 3rd edition pub. in Warsaw, 1878), who, citing Cyriacus Spangenberg, writes that the Czech Republic was formerly called Bohemia (Latin: Boihaemum). Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1) simply writes for Ashkenaz that he was the progenitor of the people whom the Greeks call Rheginians, a people which Isidore of Seville (2006:193) identified with Sarmatians. Jonathan ben Uzziel, who rendered an Aramaic translation of the Book of Jeremiah in the early 1st-century CE, wrote that Ashkenaz in Jeremiah 51:27 is Hurmini (Jastrow: "probably a province of Armenia"), and Adiabene, suggesting that the descendants of Ashkenaz had also originally settled there.

- ^ R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32) in his translation of Genesis 10:3 thought Rifath to be the progenitor of the Franks, whom he called in Judeo-Arabic פרנגה. In contrast, Abarbanel (1960:173), like Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1), opined that the descendants of Rifath settled in Paphlagonia, a region corresponding with Cappadocia (Roman province) in Asia Minor. Abarbanel added that some of these people (from Paphlagonia) eventually made their way into Venice, in Italy, while others went to France and to Lesser Britain (Brittany) where they settled along the Loire river. According to Josippon (1971:1), Rifath was the ancestor of the indigenous peoples of Brittany. The author of the Midrash Rabba (on Genesis Rabba §37) takes a different view, alleging that the descendants of Rifath settled in Adiabene.

- ^ Togarmah is considered by medieval Jewish scholars as being the progenitor of the original Turks, of whom were the Phrygians, according to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1). According to R. Judah Halevi in his Kuzari, and according to the book Josippon (book I), Togarmah fathered ten sons, who were these: 1. Kuzar (Khazar; Cusar), actually the seventh son of Togarmah, and whose progeny became known as Khazars. In a letter written by King Joseph of the Khazar to Hasdai ibn Shaprut, he claimed that he and his people are descended from Japheth, through son Togarmah; 2. Pechineg (Pizenaci), the ancestor of a people that settled along the Danube River. Some Pechenegs had also settled along the river Atil (Volga), and likewise on the river Geïch (Ural), having common frontiers with the Khazars and the so-called Uzes; 3. Elikanos; 4. Bulgar, the ancestor of the early inhabitants of Bulgaria. Descendants of these people also settled along the lower courses of the Danube River, as well as in the region of Kazan, in Tatarstan; 5. Ranbina; 6. Turk, perhaps the ancestor of the Phrygians of Asia Minor (Turkey); 7. Buz; 8. Zavokh; 9. Ungar, the ancestor of the early inhabitants of Hungary. These also settled along the Danube River; 10. Dalmatia, the ancestors of the first inhabitants of Croatia. According to a redaction of the Georgian Chronicles made by Vakhtang VI of Kartli, Togarmah was also the ancestor of Kavkas (Caucas), who fathered the Chechen and Ingush peoples.

- ^ According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32 - note 9), some of Togarmah's descendants settled in Tadzhikistan in central Asia. Jonathan ben Uzziel, who rendered an Aramaic translation of the Book of Ezekiel in the early 1st-century CE, wrote that Togarmah in Ezekiel 27:14 is the province of Germamia (var. Germania), suggesting that his descendants had originally settled there. The same view is taken by the author of the Midrash Rabba (Genesis Rabba §37).

- ^ Asia, the sense being to Asia Minor. In the language employed by Israel's Sages, this place is always associated with the western part of Turkey, the largest city of which region during the period of Israel's sages being Ephesus, situated on the coast of Ionia, near present-day Selçuk, Izmir Province, in west Turkey (cf. Josephus, Antiquities 14.10.11).

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.1), and R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32), Kitim was the father of the indigenous peoples who inhabited the isle of Cyprus. According to Josippon (1971:2), Kitim was also the forebear of the Romans who settled along the Tiber river, in the Campus Martius flood plain. Jonathan ben Uzziel, who rendered an Aramaic translation of the Book of Ezekiel in the early 1st-century CE, wrote that the Kitim in Ezekiel 27:6 is the province of Apulia, suggesting that his descendants had originally settled there.

- ^ According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32 - note 13), the descendants of Dodanim settled in Adana, a city in southern Turkey, on the Seyhan River. According to Josippon (1971:2), Dodanim was the forebear of the Croatians and the Slovenians, among other nations. Abarbanel (1960:173) held that the descendants of Dodanim settled the isle of Rhodes.

- ^ Now called Ilida (in southern Greece on the Peloponnese).

- ^ This place is distinguished by being the northwestern part of the Peloponnese peninsula.

- ^ Misrayim was the progenitor of the indigenous Egyptians, from whom are descended the Copts. Misrayim's sons were Ludim, Anamim, Lehabim, Naphtuhim, Pathrusim, Casluhim (out of whom came Philistim), and Caphtorim.

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.2), and Abarbanel (1960:173), Fūṭ is the progenitor of the indigenous peoples of Libya. R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32 - note 15) writes in Judeo-Arabic that Fūṭ's name has been preserved as an eponym in the town called תפת, and which Yosef Qafih thought may have been the town תוות mentioned by Ibn Battuta, a town in the Sahara bounded by present-day Morocco.

- ^ The reference here is to Canaan, who became the father of eleven sons, the descendants of whom leaving the names of their fathers as eponyms in their respective places where they came to settle (e.g. Ṣīdon, Yəḇūsī, etc. See Descendants of Canaan). The children of Canaan had initially settled the regions south of the Taurus Mountains (Amanus) stretching as far as the border of Egypt. During the Israelite's conquest of Canaan under Joshua, some of the Canaanites were expelled and went into North Africa, settling initially in and around Carthage; on this account see Epiphanius (1935), p. 77 (75d - §79) and Midrash Rabba (Leviticus Rabba 17:6), where, in the latter case, Joshua is said to have written three letters to the Canaanites, requesting them to either take leave of the country, or make peace with Israel, or engage Israel in warfare. The Gergesites took leave of the country and were given a country as beautiful as their own in Africa propria. The Tosefta (Shabbat 7 [8]:25) mentions the country in respect to the Amorites who went there.

- ^ Not identified. Possibly a region in Libya. Jastrow has suggested that the place may have been an Egyptian eparchy or nomos, probably Heracleotes. The name also appears in Rav Yosef's Aramaic Targum of I Chronicles 1:8–ff.

- ^ Sebā is thought to have left his name to the town of Saba, which name, according to Josephus (Antiquities 2.10.2.), was later changed by Cambyses the Persian to Meroë, after the name of his own sister. Sebā's descendants are thought to have originally settled in Meroë, along the banks of the upper Nile River.

- ^ According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32), this man's descendants are said to have settled in Zawilah, a place explained by medieval traveler Benjamin of Tudela as being "the land of Gana (Fezzan south of Tripoli)," situated at a distance of a 62-day caravan-journey, going westward from Assuan in Egypt, and passing through the great desert called Sahara. See Adler (2014), p. 61). The Arab chronicler and geographer, Ibn Ḥaukal (travelled 943-969 CE), says of Zawilah that it is a place in the eastern part of the Maghreb, adding that "from Kairouan (Tunis) to Zawilah is a journey of one month." Abarbanel (1960:174), like Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.2.), explains this strip of country to be inhabited by the Gaetuli, and which place is described by Pliny in his Natural History as being between Libya and a stretch of desert as one travels southward. The 10th-century Karaite scholar, Yefet ben Ali (p. 114 - folio A), identified "the land of Havilah" in Genesis 2:11 with "the land of Zawilah," and which he says is a land "encompassed by the Pishon river," a river which he identified as the Nile River, based on an erroneous, medieval-Arab geographical perspective where the Niger River was thought to be an extension of the Nile River. See Ibn Khaldun (1958:118). In contrast, Yefet ben Ali identified the Gihon River of Genesis 2:13 with that of Amu Darya (al-Jiḥān / Jayhon of the Islamic texts), and which river encircled the entire Hindu Kush. Ben Ali's interpretation stands in direct contradiction to Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, where it assigns the "land of Havilah" (in Gen. 2:11) to the "land of India."

- ^ According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32 - note 18), Savtah was the forebear of the peoples who originally settled in Zagāwa, a place thought to be identical with Zaghāwa in the far-western regions of Sudan, and what is also called Wadai. According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.2.), the descendants of Savtah were called by the Grecians "Astaborans," a northeastern Sudanic people.

- ^ According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32), Savteḫā was the progenitor of the inhabitants of Demas, probably the ancient port city and harbour in Tunisia, mentioned by Pliny, now an extensive ruin along the Barbary Coast called Ras ed-Dimas, located ca. 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from the island of Lampedusa, and ca. 200 kilometres (120 mi) southeast of Carthage.

- ^ Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.2.) calls the descendants of Dedan "a people of western Aethiopia" and which place "they founded as a colony" (Αἰθιοπικὸν ἔθνος τῶν ἑσπερίων οἰκίσας). R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32 - note 22), in contrast, thought that the children of Dedan came to settle in India.

- ^ Also known as Byzacium, or what is now called Tunisia.

- ^ Mezağ is now El-Jadida in Morocco.

- ^ According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:33 - note 47), the descendants of Elam settled in Khuzestan (Elam), and which, according to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.) were "the ancestors of the ancient Persians."

- ^ According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:33 - note 48), Ashur was the progenitor of the Assyrian race, whose ancestral territory is around Mosul in northern Iraq, near the ancient city of Nineveh. The same view was held by Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.).

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.), Arphaxad's descendants became known by the Greeks as Chaldeans (Chalybes), who inhabited the region known as Chaldea, in present-day Iraq.

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.), Lud was the forebear of the Lydians. The Asatir describes the descendants of two of the sons of Shem, viz. Laud (Ld) and Aram, as also having settled in a region of Afghanistan formerly known as Khorasan (Charassan), but known by the Arabic-speaking peoples of Afrikia (North Africa) as simply "the isle" (Arabic: Al-gezirah). (see: Moses Gaster (ed.), The Asatir: The Samaritan Book of the "Secrets of Moses", The Royal Asiatic Society: London 1927, p. 232)

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.), Aram was the progenitor of the Syrians, a people who originally settled along the Euphrates River and, later, all throughout the region of Syria. R. Saadia Gaon (1984:33 - note 49), dissenting, thought that Aram was the progenitor of the Armenian people.

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.), the descendants of Uz founded the cities of Trachonitis and Damascus. R. Saadia Gaon (1984:33 - note 50) possessed a tradition that Uz's descendants also settled the region in Syria known as Ghouta.

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.), the descendants of Hul (Ul) founded Armenia. Ishtori Haparchi (2007:88), dissenting, thought that Hul's descendants settled in the region known as Hulah, south of Damascus and north of Al-Sanamayn (Ba'al Maon).

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.), the descendants of Gether founded Bactria. Josephus is most-likely referring here to the Kushans (of the Pamirs mountain range), who, according to the Chinese historian and geographer Yu Huan (2004: section 5, note 13), had overrun Bactria and settled there in the late second-century BCE. Prior to this time, the region had been settled by rulers of Greek descent and heritage who had been there since Alexander's conquest c. 328 BCE. The Bactrians of Kushan descent are known in Chinese as Da Yuezhi. The old Bactria (Chinese: Daxia) is thought to have included northern Afghanistan, including Badakhshan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, as far as the region of Termez in the west. Prior to the arrival of the Yuezhi in Bactria, they had lived in and around the area of Xinjiang (Western China) where the first known reference to the Yuezhi was made in c. 645 BCE by the Chinese Guan Zhong in his work Guanzi (管子, Guanzi Essays: 73: 78: 80: 81). He described the Yúshì 禺氏 (or Niúshì 牛氏), as a people from the north-west who supplied jade to the Chinese from the nearby mountains (also known as Yushi) in Gansu (see: Iaroslav Lebedynsky, Les Saces, ISBN 2-87772-337-2, p. 59).

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4.), the descendants of Mash settled the region known in classical antiquity as Charax Spasini.

- ^ Whose posterity were known as the "Hebrews", after the name of their forebear.

- ^ From Peleg's line descended the Israelites, the descendants of Esau, and the Arabian nations (Ishmaelites), among other peoples - all sub-nations.

- ^ In the South Arabian tradition, he is today known by the name Qaḥṭān, the progenitor of the Sabaean-Himyarite tribes of South Arabia. See Saadia Gaon (1984:34) and Luzzatto, S.D. (1965:56).

- ^ According to Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74), Almodad's descendants settled along the "coastal plains," without naming the country.

- ^ According to Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983), p. 74, Sheleph's descendants settled along the "coastal plains," without naming the country.

- ^ Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74), a place now called in southern Yemen by the name Ḥaḍramawt. Pliny, in his Natural History, mentions this place under the name Chatramotitae.

- ^ Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74) calls the place inhabited by Jerah's descendants "Ibn Qamar" ("the son of Moon") – an inference to the word "Jerah" (Heb. ירח) which means "moon," and where he says are now the towns of Dhofar in Yemen, and Qalhāt in Oman, and al-Shiḥr (ash-Shiḥr).

- ^ a b Nethanel ben Isaiah 1983, p. 74.

- ^ The old appellation given to the city of Sana'a in Yemen was Uzal. Uzal's descendants are thought to have settled there. See Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74); Luzzatto, S.D. (1965:56); and see Al-Hamdāni (1938:8, 21), where it was later known under its Arabic equivalent Azāl.

- ^ According to Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74), Diklah's posterity were said to have founded the city of Beihan.

- ^ A place which Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74), calls in Judeo-Arabic אלאעבאל = al-iʻbāl.

- ^ According to Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74), Abimael's posterity inhabited the place called Al-Jawf.

- ^ Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74) calls the land settled by Havilah's posterity as being "a land inhabited in the east". Targum Pseudo-Jonathan ascribes the "land of Havilah" in Genesis 2:11 to the "land of India." Josephus (Antiquities 1.1.3.), writing on the same verse, says that "Havilah" is a place in India, traversed by the Ganges River.

- ^ Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:74), calls the land settled by Jobab's posterity as being "a land inhabited in the east".

- ^ According to Josephus (Antiquities 1.6.4. [1.147]), the posterity of Joktan settled all those regions "proceeding from the river Cophen (a tributary of the Indus), inhabiting parts of India (Ἰνδικῆς) and of the adjacent country Seria (Σηρίας)." Of this last country, Isidore of Seville (2006:194) wrote: "The Serians (i.e. Chinese, or East Asians generally), a nation situated in the far East, were allotted their name from their own city. They weave a kind of wool that comes from trees, hence this verse 'The Serians, unknown in person, but known for their cloth'."

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History Vol. II pt. 2, p. 425

- ^ Barry Cunliffe (ed.), The Oxford History of Prehistoric Europe (Oxford University Press, 1994), pp. 381–382.

- ^ Daniel Block (2013), Beyond the River Chebar: Studies in Kingship and Eschatology in the Book of Ezekiel, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Day 2021, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Hendel 2024, p. 362.

- ^ Emmet John Sweeny, Empire of Thebes, Or Ages in Chaos Revisited, 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Bromiley, Geoffrey William, ed. (1994). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Volume Two: Fully Revised: E-J: Javan. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 971. ISBN 0-8028-3782-4.

- ^ a b c Jacob Milgrom; Daniel I. Block (14 September 2012). Ezekiel's Hope: A Commentary on Ezekiel 38-48. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-61097-650-3.

- ^ Annick Payne (17 September 2012). Iron Age Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-58983-658-7.

- ^ a b c Josephus, Flavius. The Antiquities of the Jews 1.6.1. Translated by William Whiston. Greek original.

- ^ a b Gill's Exposition of the Entire Bible, Genesis 10:3.

- ^ The expansion of the Greek world, eighth to sixth centuries B.C., John Boardman, Volume 3 Cambridge Ancient History, Cambridge University Press, 1982, ISBN 0-521-23447-6, ISBN 978-0-521-23447-4

- ^ "Now, this Elishah is often identified with Alashiya in the scholarly literature, an ancient name often associated with Cyprus or a part of the island." Gard Granerød (26 March 2010). Abraham and Melchizedek: Scribal Activity of Second Temple Times in Genesis 14 and Psalm 110. Walter de Gruyter. p. 116. ISBN 978-3-11-022346-0.

- ^

Emil G. Hirsch (1901–1906). "Elishah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Emil G. Hirsch (1901–1906). "Elishah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ "MikraotGedolot – AlHaTorah.org". mg.alhatorah.org. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b Barnes' Notes on the Bible Gen. 10:4

- ^ a b Clarke's Commentary on the Bible Gen 10:4

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2003). On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids and Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 593. ISBN 9780802849601.

- ^ Hendel 2024, p. 364.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hendel 2024, p. 365.

- ^ Sadler, Jr., Rodney (2009). "Put". In Katharine Sakenfeld (ed.). The New Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible. Vol. 4. Nashville: Abingdon Press. pp. 691–92.

- ^ Müller, W. W. (1992). "Havilah (Place)." In the Anchor Bible Dictionary. Volume 3, p. 82.

- ^ Burrowes, Robert D. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Yemen. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 319. ISBN 978-0810855281.

- ^ St. John Simpson (2002). Queen of Sheba: treasures from ancient Yemen. British Museum Press. p. 8. ISBN 0714111511.

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth Anderson (2003). On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 0802849601.

- ^ Day 2021, p. 176.

- ^ Day 2021, p. 178.

- ^ Hendel 2024, p. 370–371.

- ^ a b c Hendel 2024, p. 371.

- ^ Archibald Henry Sayce (2009). The "Higher Criticism" and the Verdict of the Monuments. General Books LLC. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-150-17885-6. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Strange, J. Caphtor/Keftiu: A New Investigation (Leiden: Brill) 1980

- ^ a b c d e f Hendel 2024, p. 372.

- ^ Dallaire, Helene (2017). Joshua. Zondervan Academic. ISBN 978-0-310-53177-7.

- ^ a b c Hendel 2024, p. 373.

- ^ a b c Hendel 2024, p. 374.

- ^ a b c d e Hendel 2024, p. 375.

- ^ a b Day 2021, p. 187.

- ^ McKinny 2021, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Day 2021, p. 181.

- ^ a b c Hendel 2024, p. 376.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hendel 2024, p. 377.

- ^ Zwickel, Wolfgang (May 2024). "Ofir". Das wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet (WiBiLex) (in German). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft.

- ^ Ramaswami, Sastri, The Tamils and their culture, Annamalai University, 1967, pp.16

- ^ Gregory, James, Tamil lexicography, M. Niemeyer, 1991, pp.10

- ^ Fernandes, Edna, The last Jews of Kerala, Portobello, 2008, pp.98

- ^ Rensberger, Boyce (24 May 1976). "Solomon's Mine Believed Found". The New York Times.

- ^ Hendel 2024, pp. 377–378.

- ^ D'Souza (1995), p. 124

- ^ According to Eusebius' Onomasticon, after the Hivites were destroyed in Gaza, they were supplanted by people who came there from Cappadocia. See Notley, R.S., et al. (2005), p. 62

- ^ According to an ancient Jewish teaching in Mishnah (Yadayim 4:4), Sennacherib, the king of Assyria, came up and put all the nations in confusion. Therefore, Judah, a person who thought he was of Ammonite descent, was permitted to marry a daughter of Israel.

- ^ A case study are the Bulgar tribes who, in the 7th-century, migrated to the lower courses of the rivers Danube, Dniester and Dniepr. Being influenced by the Goths, they at one time spoke a Germanic language, evidenced by the 4th-century translation of the Wulfila Bible by a small Gothic community in Nicopolis ad Istrum (a place in northern Bulgaria). Later, because of an influx of south Slavs in the region from the 6th century, they adopted a common language on the basis of Slavonic.

- ^ A case in point is Bethuel the Aramean ("Syrian") in Gen. 25:20, who was called an "Aramean", not because he was descended from Aram, but because he lived in the country of the Aramaeans (Syrians). So explains Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983:121–122).

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Yebamot 62a, RASHI, s.v. חייס; ibid. Baba Bathra 109b. Cf. Maimonides, Mishne Torah (Hil. Nahalot 1:6).

- ^ This was observed as early as 1734, in George Sale's Commentary on the Quran.

- ^ Klijn, Albertus (1977). Seth: In Jewish, Christian and Gnostic Literature. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-05245-3., page 54

- ^ S.P. Brock notes that the earliest Greek texts of Pseudo-Methodius read Moneton, while the Syriac versions have Ionţon (Armenian Apocrypha, p. 117)

- ^ Gascoigne, Mike. "Travels of Noah into Europe". www.annomundi.com.

- ^ Whiston, William (1708). "A New Theory of the Earth: From Its Original, to the Consummation of All Things. Wherein the Creation of the World in Six Days, the Universal Deluge, and the General Conflagration, as Laid Down in the Holy Scriptures, are Shewn to be Perfectly Agreeable to Reason and Philosophy. With a Large Introductory Discourse Concerning the Genuine Nature, Stile, and Extent of the Mosaick History of the Creation".

- ^ Hutton, Christopher (2008). "Human diversity and the genealogy of languages: Noah as the founding ancestor of the Chinese". Language Sciences. 30 (5): 512–528. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2007.07.004.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abarbanel, Isaac (1960). Commentary of Abarbanel on the Torah (Genesis) (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Jerusalem: Bene Arbel Publishers. (an English translation published in 2016, by the Golan Abarbanel Research Institute, OCLC 1057900303)

- Adler, Elkan Nathan (2014). Jewish Travellers. London: Routledge. OCLC 886831002. (first printed in 1930)

- Alexander, Philip (1988). "Retelling the Old Testament". It is Written: Scripture Citing Scripture: Essays in Honour of Barnabas Lindars, SSF. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521323475.

- Al-Hamdāni, al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad (1938). The Antiquities of South Arabia - The Eighth Book of Al-Iklīl. Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 251493869. (reprinted in Westport Conn. 1981)

- Ben Abraham al-Fasi, David (1936). Solomon Skoss (ed.). The Hebrew-Arabic Dictionary of the Bible, Known as 'Kitāb Jāmiʿ al-Alfāẓ' (Agron) of David ben Abraham al-Fasi (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 46. OCLC 840573323.

- Ben Maimon, Moses (1956). Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer (2nd ed.). New York: Dover Publishers. OCLC 318937112.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1–11. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567372871.

- Bøe, Sverre (2001). Gog and Magog: Ezekiel 38–39 as pre-text for Revelation 19, 17–21 and 20, 7–10. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161475207.

- Brodie, Thomas L. (2001). Genesis As Dialogue: A Literary, Historical, and Theological Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198031642.

- Carr, David McLain (1996). Reading the Fractures of Genesis: Historical and Literary Approaches. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664220716.

- Day, John (2014). "Noah's Drunkenness, the Curse of Canaan". In Baer, David A.; Gordon, Robert P. (eds.). Leshon Limmudim: Essays on the Language and Literature of the Hebrew Bible in Honour of A.A. Macintosh. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567308238.

- Day, John (2021). "The Table of the Nations in Genesis 10". From Creation to Abraham: Further Studies in Genesis 1-11. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-70311-8.

- Dillmann, August (1897). Genesis: Critically and Exegetically Expounded. Vol. 1. Edinburgh, UK: T. and T. Clark. p. 314.

- D'Souza, Dinesh (1995). The End of Racism. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster Audio. ISBN 0671551299. OCLC 33394422.

- Epiphanius (1935). James Elmer Dean (ed.). Epiphanius' Treatise on Weights and Measures - The Syriac Version. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 123314338.

- Gmirkin, Russell (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9780567134394.

- Hendel, Ronald (2024). Genesis 1-11: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14973-9.

- Ibn Khaldun (1927). Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique septentrionale (Histoire des Dynasties Musulmanes) (in French). Vol. 2. Translated by Baron de Slane. Paris: P. Geuthner. OCLC 758265555.

- Ibn Khaldun (1958). The Muqaddimah: an introduction to history. Vol. 1. Translated by Franz Rosenthal. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. OCLC 956182402.

- Ishtori Haparchi (2007). Avraham Yosef Havatzelet (ed.). Sefer Kaftor Ve'ferah (in Hebrew). Vol. 2 (chapter 11) (3 ed.). Jerusalem: Bet ha-midrash la-halakhah ba-hityashvut. OCLC 32307172.

- Isidore of Seville (1970). History of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi. Translated by Guido Donini and Gordon B. Ford, Jr. Leiden: E.J. Brill. OCLC 279232201.

- Isidore of Seville (2006). Barney, Stephen A.; Lewis, W.J.; Beach, J.A. (eds.). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83749-1. OCLC 1130417426.

- Josephus (1998). Jewish Antiquities. The Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 1. Translated by Henry St. John Thackeray. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674995759.

- Josippon (1971). Hayim Hominer (ed.). Josiphon by Joseph ben Gorion Hacohen (3 ed.). Jerusalem: Hominer Publication. pp. 1–2. OCLC 776144459. (reprinted in 1978)

- Kaminski, Carol M. (1995). From Noah to Israel: Realization of the Primaeval Blessing After the Flood. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567539465.

- Keiser, Thomas A. (2013). Genesis 1–11: Its Literary Coherence and Theological Message. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781625640925.

- Knoppers, Gary (2003). "Shem, Ham and Japheth". In Graham, Matt Patrick; McKenzie, Steven L.; Knoppers, Gary N. (eds.). The Chronicler as Theologian: Essays in Honor of Ralph W. Klein. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826466716.

- Kautzsch, E.F. The Early Narratives of Genesis. (quoted in Orr, James (1917). The Fundamentals. Vol. 1. Los Angeles, CA: Biola Press.)

- Leo Africanus (1974). Robert Brown (ed.). History and Description of Africa. Vol. 1–3. Translated by John Pory. New York Franklin. OCLC 830857464. (reprinted from London 1896)

- Luzzatto, S.D. (1965). P. Schlesinger (ed.). S.D. Luzzatto's Commentary to the Pentateuch (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Tel-Aviv: Dvir Publishers. OCLC 11669162.

- Macbean, A. (1773). A Dictionary of Ancient Geography: Explaining the Local Appellations in Sacred, Grecian, and Roman History. London: G. Robinson. OCLC 6478604.

- Machiela, Daniel A. (2009). "A Comparative Commentary on the Earths Division". The Dead Sea Genesis Apocryphon: A New Text and Translation With Introduction and Special Treatment of Columns 13–17. BRILL. ISBN 9789004168145.

- Matthews, K.A. (1996). Genesis 1–11:26. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9781433675515.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780881461015.

- McKinny, Chris (2021). "Finding Mash and His Brothers – The Historical Geography of the "Sons" of Aram (Gen 10:23; 1 Chr 1:17)". In Maeir, Aren M.; Pierce, George A. (eds.). To Explore the Land of Canaan: Studies in Biblical Archaeology in Honor of Jeffrey R. Chadwick. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-075780-4.

- Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983). Sefer Me'or ha-Afelah (in Hebrew). Translated by Yosef Qafih. Kiryat Ono: Mechon Moshe. OCLC 970925649.

- Neubauer, A. (1868). Géographie du Talmud (in French). Paris: Michel Lévy Frères.

- Notley, R.S.; Safrai, Z., eds. (2005). Eusebius, Onomasticon: The Place Names of Divine Scripture. Boston / Leiden: E.J. Brill. OCLC 927381934.

- Pietersma, Albert; Wright, Benjamin G. (2005). A New English Translation of the Septuagint. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743971.

- Rogers, Jeffrey S. (2000). "Table of Nations". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Ruiten, Jacques T. A. G. M. (2000). Primaeval History Interpreted: The Rewriting of Genesis 1–11 in the Book of Jubilees. BRILL. ISBN 9789004116580.

- Saadia Gaon (1984). Yosef Qafih (ed.). Rabbi Saadia Gaon's Commentaries on the Pentateuch (in Hebrew) (4 ed.). Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook. OCLC 232667032.

- Saadia Gaon (1984b). Moshe Zucker (ed.). Saadya's Commentary on Genesis (in Hebrew). New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America. OCLC 1123632274.

- Sadler, Rodney Steven Jr. (2009). Can a Cushite Change His Skin?: An Examination of Race, Ethnicity, and Othering in the Hebrew Bible. A&C Black. ISBN 9780567027658.

- Sailhamer, John H. (2010). The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition and Interpretation. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830878888.

- Scott, James M. (2005). Geography in Early Judaism and Christianity: The Book of Jubilees. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521020688.

- Sozomen; Philostorgius (1855). The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen and The Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius. Translated by Edward Walford. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 224145372.

- Strawn, Brent A. (2000a). "Shem". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Strawn, Brent A. (2000b). "Ham". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (1974). M. Ginsburger (ed.). Pseudo-Jonathan (Thargum Jonathan ben Usiël zum Pentateuch (in Hebrew). Berlin: S. Calvary & Co. OCLC 6082732. (First printed in 1903, Based on British Museum add. 27031)

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2014). "Narrative Reiteration and Comparative Literature: Problems in Defining Dependency". In Thompson, Thomas L.; Wajdenbaum, Philippe (eds.). The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Routledge. ISBN 9781317544265.

- Towner, Wayne Sibley (2001). Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664252564.

- Uehlinger, Christof (1999). "Nimrod". In Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter (eds.). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Brill. ISBN 9780802824912.

- Wajdenbaum, Philippe (2014). Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. Routledge. ISBN 9781317543893.

- Yefet ben Ali (n.d.). Yefet ben Ali's Commentary on the Torah (Genesis) - Ms. B-51 (in Hebrew). St. Petersburg, Russia: Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Yu Huan (2004), "The Peoples of the West", Weilue 魏略, translated by John E. Hill (section 5, note 13) (This work, published in 429 CE, is a recension of Yu Huan's Weilue ("Brief Account of the Wei Dynasty"), the original having now been lost)

External links

[edit]- Jewish Encyclopedia: Entry for "Genealogy"