Kumbh Mela

| Kumbh Mela Kumbha Mela | |

|---|---|

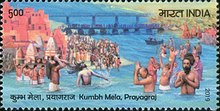

Prayag Kumbh Mela in 2001 | |

| Genre | Pilgrimage |

| Frequency | Every twelve years |

| Location(s) | Alternately in

Prayagraj, Haridwar, Nashik and Ujjain (After 700 years of closure, Bansberia Tribeni Sangam's Kumbh Mela has started again in 2022. But the Bansberia Kumbha Mela is not inscribed under UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage ) |

| Kumbh Mela | |

|---|---|

| Country | India |

| Reference | 01258 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2017 (12th session) |

| List | Representative |

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Kumbh Mela or Kumbha Mela (/ˌkʊmb ˈmeɪlə/) is a major pilgrimage and festival in Hinduism. On 4 February 2019, Kumbh Mela witnessed the largest peaceful public gathering of humans ever recorded.[1] It is celebrated in a cycle of approximately 12 years, to celebrate every revolution Brihaspati (Jupiter) completes[2]. Kumbh is mainly held at four riverside pilgrimage sites, namely: Prayagraj (Ganges-Yamuna-Sarasvati rivers confluence), Haridwar (Ganges), Nashik (Godavari), and Ujjain (Shipra);[1][3] But now the Kumbh Mela has been revived at a fifth place too.[4] The other rejuvenated Kumbh Mela is celebrated at Bansberia Tribeni Sangam in West Bengal at the confluence of Hooghly and Saraswati river, dates back thousands of years but was stopped 700 years ago, but this Kumbh Mela has been reopened since 2022.[5][4][6]

The festival is marked by a ritual dip in the waters, but it is also a celebration of community commerce with numerous fairs, education, religious discourses by saints, mass gatherings of monks, and entertainment.[7][8] The seekers believe that bathing in these rivers is a means to prāyaścitta (atonement, penance, restorative action) for past mistakes,[9] and that it cleanses them of their sins.[10]

The festival is traditionally credited to the 8th-century Hindu philosopher and saint Adi Shankara, as a part of his efforts to start major Hindu gatherings for philosophical discussions and debates along with Hindu monasteries across the Indian subcontinent.[1] However, there is no historical literary evidence of these mass pilgrimages called "Kumbha Mela" prior to the 19th century. There is ample evidence in historical manuscripts[11] and inscriptions[12] of an annual Magha Mela in Hinduism – with periodic larger gatherings after 6 or 12 years – where pilgrims gathered in massive numbers and where one of the rituals included a sacred dip in a river or holy tank. According to Kama MacLean, the socio-political developments during the colonial era and a reaction to Orientalism led to the rebranding and remobilisation of the ancient Magha Mela as the modern era Kumbh Mela, particularly after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[3]

The weeks over which the festival is observed cycle at each site approximately once every 12 years[note 1] based on the Hindu luni-solar calendar and the relative astrological positions of Jupiter, the sun and the moon. The difference in Prayag and Haridwar festivals is about 6 years, and both feature a Maha (major) and Ardha (half) Kumbh Melas. The exact years – particularly for the Kumbh Melas at Ujjain and Nashik – have been a subject of dispute in the 20th century. The Nashik and Ujjain festivals have been celebrated in the same year or one year apart,[14] typically about 3 years after the Allahabad / Prayagraj Kumbh Mela.[15] Elsewhere in many parts of India, similar but smaller community pilgrimage and bathing festivals are called the Magha Mela, Makar Mela or equivalent. For example, in Tamil Nadu, the Magha Mela with water-dip ritual is a festival of antiquity. This festival is held at the Mahamaham tank (near Kaveri river) every 12 years at Kumbakonam, attracts millions of South Indian Hindus and has been described as the Tamil Kumbh Mela.[16][17] Other places where the Magha-Mela or Makar-Mela bathing pilgrimage and fairs have been called Kumbh Mela include Kurukshetra,[18][19] Sonipat,[20] and Panauti (Nepal).[21]

The Kumbh Melas have three dates around which the significant majority of pilgrims participate, while the festival itself lasts between one[22] and three months around these dates.[23] Each festival attracts millions, with the largest gathering at the Prayag Kumbh Mela and the second largest at Haridwar.[24] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica and Indian authorities, more than 200 million Hindus gathered for the Kumbh Mela in 2019, including 50 million on the festival's most crowded day.[1] The festival is one of the largest peaceful gatherings in the world, and considered as the "world's largest congregation of religious pilgrims".[25] It has been inscribed on the UNESCO's Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[26][27] The festival is observed over many days, with the day of Amavasya attracting the largest number on a single day. The Kumbh Mela authorities said that the largest one-day attendance at the Kumbh Mela was 30 million on 10 February 2013,[28][29] and 50 million on 4 February 2019.[30][31][32]

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]The Kumbha in Kumbha Mela literally means "pitcher, jar, pot" in Sanskrit.[33] It is found in the Vedic texts, in this sense, often in the context of holding water or in mythical legends about the nectar of immortality.[33] The word Kumbha or its derivatives are found in the Rigveda (1500–1200 BCE), for example, in verse 10.89.7; verse 19.16 of the Yajurveda, verse 6.3 of Samaveda, verse 19.53.3 of the Atharvaveda, and other Vedic and post-Vedic ancient Sanskrit literature.[34] In astrological texts, the term also refers to the zodiac sign of Aquarius.[33] The astrological etymology dates to late 1st-millennium CE, likely influenced by Greek zodiac ideas.[35][36][37]

The word mela means "unite, join, meet, move together, assembly, junction" in Sanskrit, particularly in the context of fairs, community celebration. This word too is found in the Rigveda and other ancient Hindu texts.[33][38] Thus, Kumbh Mela means an "assembly, meet, union" around "water or nectar of immortality".[33]

History

[edit]Many Hindus believe that the Kumbh Mela originated in times immemorial and is attested in the Hindu mythology about Samudra Manthana (lit. churning of the ocean) found in the Vedic texts.[39] Historians, in contrast, reject these claims as none of the ancient or medieval era texts that mention the Samudra Manthana legend ever link it to a "mela" or festival. According to Giorgio Bonazzoli, a scholar of Sanskrit Puranas, these are anachronistic explanations, an adaptation of early legends to a later practice by a "small circle of adherents" who have sought the roots of a highly popular pilgrimage and festival.[39][40]

The Hindu legend, however, describes the creation of a "pot of amrita (nectar of immortality)" after the forces of good and evil churn the ocean of creation. The gods and demons fight over this pot, the "kumbha", of nectar in order to gain immortality. In a later day extension to the legend, the pot is spilled at four places, and that is the origin of the four Kumbha Melas. The story varies and is inconsistent, with some stating Vishnu as Mohini avatar, others stating Dhanavantari or Garuda or Indra spilling the pot.[3] This "spilling" and associated Kumbh Mela story is not found in the earliest mentions of the original legend of Samudra Manthana (churning of the ocean) such as the Vedic era texts (pre-500 BCE).[42][43] Nor is this story found in the later era Puranas (3rd to 10th-century CE).[3][42]

While the Kumbha Mela phrase is not found in the ancient or medieval era texts, numerous chapters and verses in Hindu texts are found about a bathing festival, the sacred junction of rivers Ganga, Yamuna and mythical Saraswati at Prayag, and pilgrimage to Prayag. These are in the form of Snana (bathe) ritual and in the form of Prayag Mahatmya (greatness of Prayag, historical tour guides in Sanskrit).[44]

History

[edit]The earliest mention of Prayag and the bathing pilgrimage is found in Rigveda Pariśiṣṭa (supplement to the Rigveda).[45] It is also mentioned in the Pali canons of Buddhism, such as in section 1.7 of Majjhima Nikaya, wherein the Buddha states that bathing in Payaga (Skt: Prayaga) cannot wash away cruel and evil deeds, rather the virtuous one should be pure in heart and fair in action.[46] The Mahabharata mentions a bathing pilgrimage at Prayag as a means of prāyaścitta (atonement, penance) for past mistakes and guilt.[9] In Tirthayatra Parva, before the great war, the epic states "the one who observes firm [ethical] vows, having bathed at Prayaga during Magha, O best of the Bharatas, becomes spotless and reaches heaven."[47] In Anushasana Parva, after the war, the epic elaborates this bathing pilgrimage as "geographical tirtha" that must be combined with Manasa-tirtha (tirtha of the heart) whereby one lives by values such as truth, charity, self-control, patience and others.[48]

There are other references to Prayaga and river-side festivals in ancient Indian texts, including at the places where present-day Kumbh Melas are held, but the exact age of the Kumbh Mela is uncertain. The 7th-century Buddhist Chinese traveller Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang) mentions king Harsha and his capital of Prayag, which he states to be a sacred Hindu city with hundreds of "deva temples" and two Buddhist institutions. He also mentions the Hindu bathing rituals at the junction of the rivers.[49] According to some scholars, this is the earliest surviving historical account of the Kumbh Mela, which took place in present-day Prayag in 644 CE.[50][51][52]

Kama MacLean – an Indologist who has published articles on the Kumbh Mela predominantly based on the colonial archives and English-language media,[53] states based on emails from other scholars and a more recent interpretation of the 7th-century Xuanzang memoir, the Prayag event happened every 5 years (and not 12 years), featured a Buddha statue, involved alms giving and it might have been a Buddhist festival.[54] In contrast, Ariel Glucklich – a scholar of Hinduism and Anthropology of Religion, the Xuanzang memoir includes, somewhat derisively, the reputation of Prayag as a place where people (Hindus) once committed superstitious devotional suicide to liberate their souls, and how a Brahmin of an earlier era successfully put an end to this practice. This and other details such as the names of temples and bathing pools suggest that Xuanzang presented Hindu practices at Prayag in the 7th century, from his Buddhist perspective and perhaps to "amuse his audience back in China", states Glucklich.[49]

Other early accounts of the significance of Prayag to Hinduism is found in the various versions of the Prayaga Mahatmya, dated to the late 1st-millennium CE. These Purana-genre Hindu texts describe it as a place "bustling with pilgrims, priests, vendors, beggars, guides" and local citizens busy along the confluence of the rivers (Sangam).[44][55] These Sanskrit guide books of the medieval era India were updated over its editions, likely by priests and guides who had a mutual stake in the economic returns from the visiting pilgrims. One of the longest sections about Prayag rivers and its significance to Hindu pilgrimage is found in chapters 103–112 of the Matsya Purana.[44]

Evolution of earlier melas to Kumbh Melas

[edit]Exceedingly old pilgrimage

There is evidence enough to suggest that although the Magh Mela – or at least, the tradition of religious festival at the triveni [Prayag] – is exceedingly old, the Kumbh Mela at Allahabad is much more recent.

According to James Lochtefeld – a scholar of Indian religions, the phrase Kumbh Mela and historical data about it is missing in early Indian texts. However, states Lochtefeld, these historical texts "clearly reveal large, well-established bathing festivals" that were either annual or based on the twelve-year cycle of planet Jupiter.[56] Manuscripts related to Hindu ascetics and warrior-monks – akharas fighting the Islamic Sultanates and Mughal Empire era – mention bathing pilgrimage and a large periodic assembly of Hindus at religious festivals associated with bathing, gift-giving, commerce and organisation.[56] An early account of the Haridwar Kumbh Mela was published by Captain Thomas Hardwicke in 1796 CE.[56]

According to James Mallinson – a scholar of Hindu yoga manuscripts and monastic institutions, bathing festivals at Prayag with large gatherings of pilgrims are attested since "at least the middle of the first millennium CE", while textual evidence exists for similar pilgrimage at other major sacred rivers since the medieval period.[23] Four of these morphed under the Kumbh Mela brand during the East India Company rule (British colonial era) when it sought to control the war-prone monks and the lucrative tax and trade revenues at these Hindu pilgrimage festivals.[23] Additionally, the priests sought the British administration to recognise the festival and protect their religious rights.[23]

The 16th-century Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas mentions an annual Mela in Prayag, as does a Muslim historian's Ain-i-Akbari (c. 1590 CE).[57] The latter Akbar-era Persian text calls Prayag (spells it Priyag) the "king of shrines" for the Hindus, and mentions that it is considered particularly holy in the Hindu month of Magha.[57] The late 16th-century Tabaqat-i-Akbari also records of an annual bathing festival at Prayag sangam where "various classes of Hindus came from all sides of the country to bathe, in such numbers, that the jungles and plains [around it] were unable to hold them".[57]

The Kumbh Mela of Haridwar appears to be the original Kumbh Mela, since it is held according to the astrological sign "Kumbha" (Aquarius), and because there are several references to a 12-year cycle for it. The later Mughal Empire era texts that contain the term "Kumbha Mela" in Haridwar's context include Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh (1695–1699 CE),[57] and Chahar Gulshan (1759 CE).[58] The Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh also mentions an annual bathing pilgrimage festival in Prayag, but it does not call it Kumbh.[57] Both these Mughal era texts use the term "Kumbh Mela" to describe only Haridwar's fair, mentioning a similar fair held in Prayag and Nashik. The Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh lists the following melas: an annual mela and a Kumbh Mela every 12 years at Haridwar; a mela held at Trimbak when Jupiter enters Leo (that is, once in 12 years); and an annual mela held at Prayag (in modern Prayagraj) in Magh.[59][58]

Like the Prayag mela, the bathing pilgrimage mela at Nasik and Ujjain are of considerable antiquity. However, these were referred to as Singhasth mela, and the phrase "Kumbh mela" is yet to be found in literature prior to the 19th century. The phrases such as "Maha Kumbh" and "Ardh Kumbh" in the context of the ancient religious pilgrimage festivals with a different name at Prayag, Nasik and Ujjain are evidently of a more modern era.[60]

The Magh Mela of Prayag is probably the oldest among the four modern day Kumbh Melas. It dates from the early centuries CE, given it has been mentioned in several early Puranas.[59] However, the name Kumbh for these more ancient bathing pilgrimages probably dates to the mid-19th century. D. P. Dubey states that none of the ancient Hindu texts call the Prayag fair as a "Kumbh Mela". Kama Maclean states that the early British records do not mention the name "Kumbh Mela" or the 12-year cycle for the Prayag fair. The first British reference to the Kumbh Mela in Prayag occurs only in an 1868 report, which mentions the need for increased pilgrimage and sanitation controls at the "Coomb fair" to be held in January 1870. According to Maclean, the Prayagwal Brahmin priests of Prayag coopted the Kumbh legend and brand to the annual Prayag Magh Mela given the socio-political circumstances in the 19th century.[3]

The Kumbh Mela at Ujjain began in the 18th century, when the Maratha ruler Ranoji Shinde invited ascetics from Nashik to Ujjain for a local festival.[59] Like the priests at Prayag, those at Nashik and Ujjain, competing with other places for a sacred status, may have adopted the Kumbh tradition for their pre-existing Magha melas.[3]

Akharas: Warrior monks, recruitment drive and logistics

[edit]One of the key features of the Kumbh mela has been the camps and processions of the sadhus (monks).[62] By the 18th century, many of these had organised into one of thirteen akharas (warrior ascetic bands, monastic militia), of which ten were related to Hinduism and three related to Sikhism. Seven have belonged to the Shaivism tradition, three to Vaishnavism, two to Udasis (founded by Guru Nanak's son) and one to Nirmalas.[62] These soldier-monk traditions have been a well-established feature of the Indian society, and they are prominent feature of the Kumbh melas.[62]

Until the East India Company rule, the Kumbh Melas (Magha Melas) were managed by these akharas. They provide logistical arrangements, policing, intervened and judged any disputes and collected taxes. They also have been a central attraction and a stop for mainstream Hindus who seek their darsana (meeting, view) as well as spiritual guidance and blessings.[62] The Kumbh Melas have been one of their recruitment and initiation venues, as well as the place to trade.[23][63] These akharas have roots in the Hindu Naga (naked) monks tradition, who went to war without clothes.[62] These monastic groups traditionally credit the Kumbh mela to the 8th-century Hindu philosopher Adi Shankara, as a part of his efforts to start monastic institutions (matha),[64] and major Hindu gatherings for philosophical discussions and debates.[1] However, there is no historic literary evidence that he actually did start the Kumbh melas.[60]

During the 17th century, the akharas competed for ritual primacy, priority rights to who bathes first or at the most auspicious time, and prominence leading to violent conflicts.[62] The records from the East India Company rule era report of violence between the akharas and numerous deaths.[63][65][66] At the 1760 Kumbh Mela in Haridwar, a clash broke out between Shaivite Gosains and Vaishnavite Bairagis (ascetics), resulting in hundreds of deaths. A copper plate inscription of the Maratha Peshwa claims that 12,000 ascetics died in a clash between Shaivite sanyasis and Vaishnavite bairagis at the 1789 Nashik Kumbh Mela. The dispute started over the bathing order, which then indicated status of the akharas.[65] At the 1796 Kumbh Mela in Haridwar, violence broke out between the Shaivites and the Udasis on logistics and camping rights.[67][66]

The repetitive clashes, battle-ready nature of the warrior monks, and the lucrative tax and trading opportunities at Kumbh melas in the 18th-century attracted the attention of the East India Company officials.[23] They intervened, laid out the camps, trading spaces, and established a bathing order for each akhara. After 1947, the state governments have taken over this role and provide the infrastructure for the Kumbh mela in their respective states.[23][68]

The Kumbh Melas attract many loner sadhus (monks) who do not belong to any akharas. Of those who do belong to a group, the thirteen active akharas have been,[69]

- 7 Shaiva akharas:[note 2] Mahanirvani, Atal, Niranjani, Anand, Juna, Avahan, and Agni

- 3 Vaishnava akharas:[note 3] Nirvani, Digambar, and Nirmohi

- 3 Sikh akharas: Bara Panchayati Udasins, Chota Panchayati Udasins, and Nirmal

The ten Shaiva and Vaishnava akharas are also known as the Dasanamis, and they believe that Adi Shankara founded them and one of their traditional duties is dharma-raksha (protection of faith).[70]

Significance and impact

[edit]The Kumbh melas of the past, albeit with different regional names, attracted large attendance and have been religiously significant to the Hindus for centuries. However, they have been more than a religious event to the Hindu community. Historically the Kumbh Melas were also major commercial events, initiation of new recruits to the akharas, prayers and community singing, spiritual discussions, education and a spectacle.[7][8] During the colonial era rule of the East India Company, its officials saw the Hindu pilgrimage as a means to collect vast sums of revenue through a "pilgrim tax" and taxes on the trade that occurred during the festival. According to Dubey, as well as Macclean, the Islamic encyclopaedia Yadgar-i-Bahaduri written in 1834 Lucknow, described the Prayag festival and its sanctity to the Hindus.[57][71] The British officials, states Dubey, raised the tax to amount greater than average monthly income and the attendance fell drastically.[71][72] The Prayagwal pandas initially went along, according to colonial records, but later resisted as the impact of the religious tax on the pilgrims became clear. In 1938, Lord Auckland abolished the pilgrim tax and vast numbers returned to the pilgrimage thereafter. According to Macclean, the colonial records of this period on the Prayag Mela present a biased materialistic view given they were written by colonialists and missionaries.[72]

Baptist missionary John Chamberlain, who visited the 1824 Ardh Kumbh Mela at Haridwar, stated that a large number of visitors came there for trade. He also includes a 1814 letter from his missionary friend who distributed copies of the Gospel to the pilgrims and tried to convert some to Christianity.[73] According to an 1858 account of the Haridwar Kumbh Mela by the British civil servant Robert Montgomery Martin, the visitors at the fair included people from a number of races and clime. Along with priests, soldiers, and religious mendicants, the fair had horse traders from Bukhara, Kabul, Turkistan as well as Arabs and Persians. The festival had roadside merchants of food grains, confectioners, clothes, toys and other items. Thousands of pilgrims in every form of transport as well as on foot marched to the pilgrimage site, dressed in colourful costumes, some without clothes, occasionally shouting "Mahadeo Bol" and "Bol, Bol" together. At night the river banks and camps illuminated with oil lamps, fireworks burst over the river, and innumerable floating lamps set by the pilgrims drifted downstream of the river. Several Hindu rajas, Sikh rulers and Muslim Nawabs visited the fair. Europeans watched the crowds and few Christian missionaries distributed their religious literature at the Hardwar Mela, wrote Martin.[74]

Prior to 1838, the British officials collected taxes but provided no infrastructure or services to the pilgrims.[71][72] This changed particularly after 1857. According to Amna Khalid, the Kumbh Melas emerged as one of the social and political mobilisation venues and the colonial government became keen on monitoring these developments after the Indian rebellion of 1857. The government deployed police to gain this intelligence at the grassroots level of Kumbh Mela.[75] The British officials in co-operation with the native police also made attempts to improve the infrastructure, movement of pilgrims to avoid a stampede, detect sickness, and the sanitary conditions at the Melas. Reports of cholera led the officials to cancel the pilgrimage, but the pilgrims went on "passive resistance" and stated they preferred to die rather than obey the official orders.[75][76]

Massacres, stampedes and scandals

[edit]The Kumbh Melas have been sites of tragedies. According to Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi, the historian and biographer of the Turco-Mongol raider and conqueror Timur, Timur's armies plundered Haridwar and massacred the gathered pilgrims. The ruthlessly slaughtered pilgrims were likely those attending the Kumbh mela of 1399.[77][78][79] The Timur accounts mention the mass bathing ritual along with shaving of head, the sacred river Ganges, charitable donations, the place was at the mountainous source of the river and that pilgrims believed a dip in the sacred river leads to their salvation.[78]

Several stampedes have occurred at the Kumbh Melas. After an 1820 stampede at Haridwar killed 485 people, the Company government took extensive infrastructure projects, including the construction of new ghats and road widening, to prevent further stampedes.[80] The various Kumbh melas, in the 19th- and 20th-century witnessed sporadic stampedes, each tragedy leading to changes in how the flow of pilgrims to and from the river and ghats was managed.[81] In 1986, 50 people were killed in a stampede.[82]

The Prayag Kumbh mela in 1885 became a source of scandal when a Muslim named Husain was appointed as the Kumbh Mela manager, and Indian newspaper reports stated that Husain had "organised a flotilla of festooned boats for the pleasure of European ladies and gentlemen, and entertained them with dancing girls, liquor and beef" as they watched the pilgrims bathing.[83]

1857 rebellion and the Independence movement

[edit]According to the colonial archives, the Prayagwal community associated with the Kumbh Mela were one of those who seeded and perpetuated the resistance and 1857 rebellion to the colonial rule.[84] Prayagwals objected to and campaigned against the colonial government who supported Christian missionaries and officials who treated them and the pilgrims as "ignorant co-religionists" and who aggressively tried to convert the Hindu pilgrims to a Christian sect. During the 1857 rebellion, Colonel Neill targeted the Kumbh mela site and shelled the region where the Prayagwals lived, destroying it in what Maclean describes as a "notoriously brutal pacification of Allahabad".[84] "Prayagwals targeted and destroyed the mission press and churches in Allahabad". Once the British had regained control of the region, the Prayagwals were persecuted by the colonial officials, some convicted and hanged, while others for whom the government did not have proof enough to convict were persecuted. Large tracts of Kumbh mela lands near the Ganga-Yamuna confluence were confiscated and annexed into the government cantonment. In the years after 1857, the Prayagwals and the Kumbh Mela pilgrim crowds carried flags with images alluding to the rebellion and the racial persecution. The British media reported these pilgrim assemblies and protests at the later Kumbh Mela as strangely "hostile" and with "disbelief", states Maclean.[84]

The Kumbh Mela continued to play an important role in the independence movement through 1947, as a place where the native people and politicians periodically gathered in large numbers. In 1906, the Sanatan Dharm Sabha met at the Prayag Kumbh Mela and resolved to start the Banaras Hindu University in Madan Mohan Malaviya's leadership.[85] Kumbh Melas have also been one of the hubs for the Hindutva movement and politics. In 1964, the Vishva Hindu Parishad was founded at the Haridwar Kumbh Mela.[86]

Rising attendance and scale

[edit]

The historical and modern estimates of attendance vary greatly between sources. For example, the colonial era Imperial Gazetteer of India reported that between 2 and 2.5 million pilgrims attended the Kumbh mela in 1796 and 1808, then added these numbers may be exaggerations. Between 1892 and 1908, in an era of major famines, cholera and plague epidemics in British India, the pilgrimage dropped to between 300,000 and 400,000.[87]

During World War II, the colonial government banned the Kumbh Mela to conserve scarce supplies of fuel. The ban, coupled with false rumours that Japan planned to bomb and commit genocide at the Kumbh mela site, led to sharply lower attendance at the 1942 Kumbh mela than prior decades when an estimated 2 to 4 million pilgrims gathered at each Kumbh mela.[88] After India's independence, the attendance rose sharply. On amavasya – one of the three key bathing dates, over 5 million attended the 1954 Kumbh, about 10 million attended the 1977 Kumbh while the 1989 Kumbh attracted about 15 million.[88]

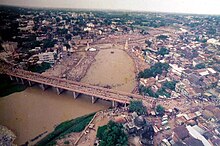

On 14 April 1998, 10 million pilgrims attended the Kumb Mela at Haridwar on the busiest single day, according to the Himalayan Academy editors.[89] In 2001, IKONOS satellite images confirmed a very large human gathering,[90][91] with officials estimating 70 million people over the festival,[91] including more than 40 million on the busiest single day according to BBC News.[92] Another estimate states that about 30 million attended the 2001 Kumbh mela on the busiest mauni amavasya day alone.[88]

In 2007, as many as 70 million pilgrims attended the 45-day long Ardha Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj.[93] In 2013, 120 million pilgrims attended the Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj.[29] Nasik has registered maximum visitors to 75 million.[10]

Maha Kumbh at Prayagraj is the largest in the world, the attendance and scale of preparation of which keeps rising with each successive celebration. For the 2019 Ardh Kumbh at Prayagraj, the preparations included the construction of a ₹42,000 million (equivalent to ₹52 billion or US$630 million in 2023) temporary city over 2,500 hectares with 122,000 temporary toilets and range of accommodation from simple dormitory tents to 5-star tents, 800 special trains by the Indian Railways, artificially intelligent video surveillance and analytics by IBM, disease surveillance, river transport management by Inland Waterways Authority of India, and an app to help the visitors.[94]

The Kumbh mela is "widely regarded as the world's largest religious gathering", states James Lochtefeld.[95] According to Kama Maclean, the coordinators and attendees themselves state that a part of the glory of the Kumbh festival is in that "feeling of brotherhood and love" where millions peacefully gather on the river banks in harmony and a sense of shared heritage.[96]

In modern religious and psychological theory, the Kumbh Mela exemplifies Émile Durkheim's concept of collective effervescence.[97] This phenomenon occurs when individuals gather in shared rituals, fostering a profound sense of unity and belonging.[98] The collective energy generated during the Mela strengthens social bonds and elevates individual and communal consciousness, illustrating the power of such gatherings to create shared identity and purpose.

Calendar, locations and preparation

[edit]Types

[edit]The Kumbh Mela are classified as:[99]

- The Purna Kumbh Mela (sometimes just called Kumbh or "full Kumbha"), occurs every 12 years at a given site.

- The Ardh Kumbh Mela ("half Kumbh") occurs approximately every 6 years between the two Purna Kumbha Melas at Prayagraj and Haridwar.[99]

- The Maha Kumbh, which occurs every 12 Purna Kumbh Melas i.e. after every 144 years.[citation needed]

For the 2019 Prayagraj Kumbh Mela, the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath announced that the Ardh Kumbh Mela (organised every 6 years) will simply be known as "Kumbh Mela", and the Kumbh Mela (organised every 12 years) will be known as "Maha Kumbh Mela" ("Great Kumbh Mela").[100]

Locations

[edit]

Numerous sites and fairs have been locally referred to be their Kumbh Melas. Of these, four sites are broadly recognised as the Kumbh Melas: Prayagraj, Haridwar, Trimbak-Nashik and Ujjain.[101][99] Other locations that are sometimes called Kumbh melas – with the bathing ritual and a significant participation of pilgrims – include Kurukshetra,[102] and Sonipat.[20]

Dates

[edit]Each site's celebration dates are calculated in advance according to a special combination of zodiacal positions of Bṛhaspati (Jupiter), Surya (the Sun) and Chandra (the Moon). The relative years vary between the four sites, but the cycle repeats about every 12 years. Since Jupiter's orbit completes in 11.86 years, a calendar year adjustment appears in approximately 8 cycles. Therefore, approximately once a century, the Kumbh mela returns to a site after 11 years.[13]

| Place | River | Zodiac[103] | Season, months | First bathing date[13] | Second date[13] | Third date[13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haridwar | Ganga | Jupiter in Aquarius, Sun in Aries | Spring, Chaitra (January–April) | Shivaratri | Chaitra Amavasya (new moon) | Mesh Sankranti |

| Prayagraj[note 4] | Ganga and Yamuna junction | Jupiter in Aries, Sun and Moon in Capricorn; or Jupiter in Taurus, Sun in Capricorn | Winter, Magha (January–February) | Makar Sankranti | Magh Amavasya | Vasant Panchami |

| Trimbak-Nashik | Godavari | Jupiter in Leo; or Jupiter, Sun and Moon enters in Cancer on lunar conjunction | Summer, Bhadrapada (August–September) | Simha sankranti | Bhadrapada Amavasya | Devotthayan Ekadashi |

| Ujjain | Shipra | Jupiter in Leo and Sun in Aries; or Jupiter, Sun, and Moon in Libra on Kartik Amavasya | Spring, Vaisakha (April–May) | Chaitra Purnima | Chaitra Amavasya | Vaisakh Purnima |

Past and future years

[edit]Kumbh Mela at Prayagraj is celebrated approximately 3 years after Kumbh at Haridwar and 3 years before Kumbh at Nashik and Ujjain (both of which are celebrated in the same year or one year apart - with Ujjain mela occurring after Nashik).[103]

| Year | Haridwar | Prayagraj | Trimbak (Nashik) | Ujjain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | ||

| 1981 | ||||

| 1982 | ||||

| 1983 | ||||

| 1984 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1985 | ||||

| 1986 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1987 | ||||

| 1988 | ||||

| 1989 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1990 | ||||

| 1991 | ||||

| 1992 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | |

| 1993 | ||||

| 1994 | ||||

| 1995 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1996 | ||||

| 1997 | ||||

| 1998 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 1999 | ||||

| 2000 | ||||

| 2001 | Maha Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2002 | ||||

| 2003 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2004 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | ||

| 2005 | ||||

| 2006 | ||||

| 2007 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2008 | ||||

| 2009 | ||||

| 2010 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2011 | ||||

| 2012 | ||||

| 2013 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2014 | ||||

| 2015 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2016 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | Kumbh Mela | ||

| 2017 | ||||

| 2018 | ||||

| 2019 | Ardh Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2020 | ||||

| 2021[104] | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2022 | ||||

| 2023 | ||||

| 2024 | ||||

| 2025 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2026 | ||||

| 2027 | Kumbh Mela | |||

| 2028 | Kumbh Mela |

Historical Festival management

[edit]The Kumbh Mela attracts tens of millions of pilgrims. Providing for a safe and pleasant temporary stay at the festival site is a complex and challenging task. The camping (santhas/akharas), food, water, sanitation, emergency health care, fire services, policing, disaster management preparations, the movement of people require significant prior planning.[105] Further, assistance to those with special needs and lost family members through Bhule-Bhatke Kendra demands extensive onsite communication and co-ordination.[105] In the case of Prayag in particular, the festival site is predominantly submerged during the monsoon months. The festival management workers have only two and a half months to start and complete the construction of all temporarily infrastructure necessary for the pilgrims, making the task even more challenging.[105]

In 2013, the Indian government authorities, in co-operation with seva volunteers, monks and Indian companies, set up 11 sectors with 55 camp clusters, providing round-the-clock first aid, ambulance, pharmacy, sector cleaning, sanitation, food and water distribution (setting up 550 kilometres (340 mi) of pipelines operated by 42 pumps), cooking fuel, and other services. According to Baranwal et al., their 13-day field study of the 2013 Kumbh mela found that "the Mela committee and all other agencies involved in Mela management successfully supervised the event and made it convenient, efficient and safe,"[105] an assessment shared by the US-based Center for Disease Control for the Nasik Kumbh mela.[106]

Rituals

[edit]Bathing and processions

[edit]

Bathing, or a dip in the river waters, with a prayer, is the central ritual of the Kumbh Melas for all pilgrims. Traditionally, on amavasya – the most cherished day for bathing – the Hindu pilgrims welcome and wait for the thirteen sadhu akharas to bathe first. This event – called shahi snan or rajyogi snan – is marked by a celebratory processional march, with banners, flags, elephants, horses and musicians along with the naked or scantily clad monks,[note 5] some smeared with bhasma (ashes).[69][107] These monastic institutions come from different parts of India, have a particular emblem symbol and deity (Ganesha, Dattatreya, Hanuman, etc.).[69][108] The largest contingent is the Juna akhara, traced to Adi Shankara, representing a diverse mix from the four of the largest Hindu monasteries in India with their headquarters at Sringeri, Dvarka, Jyotirmatha and Govardhana. The Mahanirbani and Niranjani are the other large contingents, and each akhara has their own lineage of saints and teachers. Large crowds gather in reverence and cheer for this procession of monks. Once these monks have taken the dip, the festival day opens for bathing by the pilgrims from far and near the site.[69][107][109]

The bathing ritual by the pilgrims may be aided by a Prayagwal priest or maybe a simple dip that is private. When aided, the rituals may begin with mundan (shaving of head), prayers with offerings such as flowers, sindur (vermilion), milk or coconut, along with the recitation of hymns with shradha (prayers in the honour of one's ancestors).[110] More elaborate ceremonies include a yajna (homa) led by a priest.[110] After these river-side rituals, the pilgrim then takes a dip in the water, stands up, prays for a short while, then exits the river waters. Many then proceed to visit old Hindu temples near the site.[110]

The motivations for the bathing ritual are several. The most significant is the belief that the tirtha (pilgrimage) to the Kumbh Mela sites and then bathing in these holy rivers has a salvific value, moksha – a means to liberation from the cycle of rebirths (samsara).[111] The pilgrimage is also recommended in Hindu texts to those who have made mistakes or sinned, to repent for their errors and as a means of prāyaścitta (atonement, penance) for these mistakes.[9][112] Pilgrimage and bathing in holy rivers with a motivation to do penance and as a means to self-purify has Vedic precedents and is discussed in the early dharma literature of Hinduism.[112] For example in the epic Mahabharata, the king Yudhisthira is described to be in a state full of sorrow and despair after participating in the violence of the great war that killed many. He goes to a saint, who advises him to go on a pilgrimage to Prayag and bathe in river Ganges as a means of penance.[113]

Feasts, festivities and discussions

[edit]

Some pilgrims walk considerable distances and arrive barefoot, as a part of their religious tradition. Most pilgrims stay for a day or two, but some stay the entire month of Magh during the festival and live an austere life during the stay. They attend spiritual discourses, fast and pray over the month, and these Kumbh pilgrims are called kalpavasis.[114]

The festival site is strictly vegetarian[114] by tradition, as violence against animals is considered unacceptable. Many pilgrims practice partial (one meal a day) or full vrata (day-long fasting), some abstain from elaborate meals.[110] These ritual practices are punctuated by celebratory feasts where vast number of people sit in rows and share a community meal – mahaprasada – prepared by volunteers from charitable donations. By tradition, families and companies sponsor these anna dana (food charity) events, particularly for the monks and the poor pilgrims.[110] The management has established multiple food stalls, offering delicacies from different states of India.[115][116]

Other activities at the mela include religious discussions (pravachan), devotional singing (kirtan), and religious assemblies where doctrines are debated and standardised (shastrartha).[10] The festival grounds also feature a wide range of cultural spectacles over the month of celebrations. These include kalagram (venues of kala, Indian arts), laser light shows, classical dance and musical performances from different parts of India, thematic gates reflecting the historic regional architectural diversity, boat rides, tourist walks to historic sites near the river, as well opportunities to visit the monastic camps to watch yoga adepts and spiritual discourses.[117]

Darshan

[edit]

Darshan, or viewing, is an important part of the Kumbh Mela. People make the pilgrimage to the Kumbh Mela specifically to observe and experience both the religious and secular aspects of the event. Two major groups that participate in the Kumbh Mela include the Sadhus (Hindu holy men) and pilgrims. Through their continual yogic practices the Sadhus articulate the transitory aspect of life. Sadhus travel to the Kumbh Mela to make themselves available to much of the Hindu public. This allows members of the Hindu public to interact with the Sadhus and to take "darshan". They are able to "seek instruction or advice in their spiritual lives." Darshan focuses on the visual exchange, where there is interaction with a religious deity and the worshiper is able to visually "drink" divine power. The Kumbh Mela is arranged in camps that give Hindu worshipers access to the Sadhus. The darshan is important to the experience of the Kumbh Mela and because of this worshipers must be careful so as to not displease religious deities. Seeing of the Sadhus is carefully managed and worshipers often leave tokens at their feet.[10]

In culture

[edit]Kumbh Mela has been a theme for many documentaries, including Kings with Straw Mats (1998) directed by Ira Cohen, Kumbh Mela: The Greatest Show on Earth (2001) directed by Graham Day,[118] Short Cut to Nirvana: Kumbh Mela (2004) directed by Nick Day and produced by Maurizio Benazzo,[119] Kumbh Mela: Songs of the River (2004) by Nadeem Uddin,[120] Invocation, Kumbh Mela (2008), Kumbh Mela 2013: Living with Mahatiagi (2013) by the Ukrainian Religious Studies Project Ahamot,[121] and Kumbh Mela: Walking with the Nagas (2011), Amrit: Nectar of Immortality (2012) directed by Jonas Scheu and Philipp Eyer.[122]

In 2007, National Geographic filmed and broadcast a documentary of the Prayag Kumbh Mela, named Inside Nirvana, under the direction of Karina Holden with the scholar Kama Maclean as a consultant.[114] In 2013, National Geographic returned and filmed the documentary Inside the Mahakumbh. Indian and foreign news media have covered the Kumbh Mela regularly. On 18 April 2010, a popular American morning show, CBS News Sunday Morning, extensively covered Haridwar's Kumbh Mela, calling it "The Largest Pilgrimage on Earth". On 28 April 2010, the BBC released an audio and a video report on Kumbh Mela, titled "Kumbh Mela: 'greatest show on earth'".[citation needed] On 30 September 2010, the Kumbh Mela featured in the second episode of the Sky One TV series An Idiot Abroad with Karl Pilkington visiting the festival.[citation needed]

Young siblings getting separated at the Kumbh Mela were once a recurring theme in Hindi movies.[123] Amrita Kumbher Sandhane, a 1982 Bengali feature film directed by Dilip Roy, also documents the Kumbh Mela.

Ashish Avikunthak's Bengali-language feature length fiction film Kalkimanthakatha (2015) was shot in the Prayag Kumbh Mela in 2013. In this film, two characters search for the tenth and final avatar of Lord Vishnu – Kalki, in the lines of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot.[124][125]

See also

[edit]- Barahakshetra – A semi-Kumbh Mela in Sunsari Nepal

- Mahamaham – the Tamil Kumbh Mela

- Pushkaram – the river festivals of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana

- Pushkar Fair – the springtime fair in Rajasthan, includes the tradition of a dip in the Pushkar lake

- List of largest gatherings in history

Notes

[edit]- ^ Approximately once a century, the Kumbh Mela returns after 11 years. This is because of Jupiter's orbit of 11.86 years. With each 12-year cycle per the Georgian calendar, a calendar year adjustment appears in approximately 8 cycles.[13]

- ^ They are also called Gosains.[70]

- ^ They are also called Bairagis.[70]

- ^ The sangam site is known as Prayag, sometimes Tirtharaj (lit. "king of pilgrimages")

- ^ The right to be naga, or naked, is considered a sign of separation from the material world.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Kumbh Mela: Hindu festival. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2015.

The Kumbh Mela lasts several weeks and is one of the largest festivals in the world, attracting more than 200 million people in 2019, including 50 million on the festival's most auspicious day.

- ^ "Maha Kumbh Mela 2025". kumbh.gov.in. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Maclean, Kama (2003). "Making the Colonial State Work for You: The Modern Beginnings of the Ancient Kumbh Mela in Allahabad". The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (3): 873–905. doi:10.2307/3591863. JSTOR 3591863. S2CID 162404242.

- ^ a b "Revival of age-old 'Tribeni Kumbho Mohotshav' in Bengal finds mention in PM Modi's Mann Ki Baat address". The Economic Times. 26 February 2023. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "West Bengal: Return of Tribeni Kumbh Mela after 700 years; was discontinued after Islamic invasion of Bengal". hindupost.in. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Singh, Shiv Sahay (8 June 2023). "Kumbh Mela at Tribeni: inventing tradition in West Bengal". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b Diana L. Eck (2012). India: A Sacred Geography. Harmony Books. pp. 153–155. ISBN 978-0-385-53190-0.

- ^ a b Williams Sox (2005). Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd Edition. Vol. 8. Macmillan. pp. 5264–5265., Quote: "The special power of the Kumbha Mela is often said to be due in part to the presence of large numbers of Hindu monks, and many pilgrims seek the darsan (Skt., darsana; auspicious mutual sight) of these holy men. Others listen to religious discourses, participate in devotional singing, engage brahman priests for personal rituals, organise mass feedings of monks or the poor, or merely enjoy the spectacle. Amid this diversity of activities, the ritual bath at the conjunction of time and place is the central event of the Kumbha Mela."

- ^ a b c Kane 1953, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c d e Maclean, Kama (September 2009). "Seeing, Being Seen, and Not Being Seen: Pilgrimage, Tourism, and Layers of Looking at the Kumbh Mela". CrossCurrents. 59 (3): 319–341. doi:10.1111/j.1939-3881.2009.00082.x. S2CID 170879396.

- ^ Maclean, Kama (2003). "Making the Colonial State Work for You: The Modern Beginnings of the Ancient Kumbh Mela in Allahabad". The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (3): 877–879. doi:10.2307/3591863. JSTOR 3591863. S2CID 162404242.

- ^ Monika Horstmann (2009). Patronage and Popularisation, Pilgrimage and Procession: Channels of Transcultural Translation and Transmission in Early Modern South Asia. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 135–136 with footnotes. ISBN 978-3-447-05723-3.

- ^ a b c d e James Lochtefeld (2008). Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. pp. 40 footnote 3. ISBN 978-1-134-07459-4.

- ^ Matthew James Clark (2006). The Daśanāmī-saṃnyāsīs: The Integration of Ascetic Lineages into an Order. Brill. p. 294. ISBN 978-90-04-15211-3.

- ^ K. Shadananan Nair (2004). "Mela" (PDF). Proceedings Ol'THC. UNI-SCO/1 AI IS/I Wl IA Symposium Held in Rome, December 2003. IAHS: 165. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Maclean 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Diana L. Eck (2012). India: A Sacred Geography. Harmony Books. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-385-53190-0.

- ^ Census of India, 1971: Haryana, Volume 6, Part 2, Page 137.

- ^ 1988, Town Survey Report: Haryana, Thanesar, District Kurukshetra, page 137-.

- ^ a b Madan Prasad Bezbaruah, Dr. Krishna Gopal, Phal S. Girota, 2003, Fairs and Festivals of India: Chandigarh, Delhi, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttaranchal, Uttar Pradesh.

- ^ Gerard Toffin (2012). Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara (ed.). Sins and Sinners: Perspectives from Asian Religions. BRILL Academic. pp. 330 with footnote 18. ISBN 978-90-04-23200-6.

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2008). Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-134-07459-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g James Mallinson (2016). Rachel Dwyer (ed.). Key Concepts in Modern Indian Studies. New York University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-1-4798-4869-0.

- ^ Maclean 2008, pp. 225–226.

- ^ The Maha Kumbh Mela 2001 indianembassy.org

- ^ [=00103&multinational=1#2021 Kumbh Mela] UNESCO Intangible World Heritage official list.

- ^ Kumbh Mela on UNESCO's list of intangibl Archived 7 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Economic Times, 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Over 3 crore take holy dip in Sangam on Mauni Amavasya". India Times. 10 February 2013. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016.

- ^ a b Rashid, Omar (11 February 2013). "Over three crore devotees take the dip at Sangam". The Hindu. Chennai.

- ^ Jha, Monica (23 June 2020). "Eyes in the sky. Indian authorities had to manage 250 million festivalgoers. So they built a high-tech surveillance ministate". Rest of World. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "Mauni Amavasya: Five crore pilgrims take holy dip at Kumbh till 5 pm", Times of India, 4 February 2019, retrieved 24 June 2020

- ^ "A record over 24 crore people visited Kumbh-2019, more than total tourists in UP in 2014–17". Hindustan Times. 21 May 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Nityananda Misra (2019). Kumbha: The Traditionally Modern Mela. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-93-88414-12-8.

- ^ Rigveda 10.89.7 Wikisource, Yajurveda 6.3 Wikisource; For translations see: Stephanie Jamison; Joel Brereton (2014). The Rigveda: 3-Volume Set. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972078-1.

- ^ Pingree 1973, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Yukio Ohashi 1999, pp. 719–721.

- ^ Nicholas Campion (2012). Astrology and Cosmology in the World's Religions. New York University Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-8147-0842-2.

- ^ Monier Monier Williams (Updated 2006), Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology, Mel, Melaka, Melana, Melā

- ^ a b Nityananda Misra (2019). Kumbha: The Traditionally Modern Mela. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-93-88414-12-8.

- ^ Giorgio Bonazzoli (1977). "Prayaga and Its Kumbha Mela". Purana. 19: 84–85, context: 81–179.

- ^ Prayaagasnaanavidhi, Manuscript UP No. 140, Poleman No. 3324, University of Pennsylvania Sanskrit Archives

- ^ a b Maclean 2008, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Collins, Charles Dillard (1988). The Iconography and Ritual of Śiva at Elephanta. SUNY Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-88706-773-0.

- ^ a b c Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2.

- ^ a b Krishnaswamy & Ghosh 1935, pp. 698–699, 702–703.

- ^ Bhikkhu Nanamoli (Tr); Bhikkhu Bodhi(Tr) (1995). Teachings of The Buddha: Majjhima Nikaya. p. 121. ISBN 978-0861710720.

- ^ Diana L. Eck (2013). India: A Sacred Geography. Three Rivers Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-385-53192-4.

- ^ Diane Eck (1981), India's "Tīrthas: "Crossings" in Sacred Geography, History of Religions, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 340–341 with footnote

- ^ a b Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2.

- ^ Dilip Kumar Roy; Indira Devi (1955). Kumbha: India's ageless festival. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. xxii.

- ^ Mark Tully (1992). No Full Stops in India. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-0-14-192775-6.

- ^ Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. pp. 677–. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke (2010). "Review of Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765–1954". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 41 (1): 174–175.

- ^ Maclean, Kama (2003). "Making the Colonial State Work for You: The Modern Beginnings of the Ancient Kumbh Mela in Allahabad". The Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (3): 877. doi:10.2307/3591863. JSTOR 3591863. S2CID 162404242.

- ^ Ludo Rocher (1986). The Purāṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 71–72 with footnotes. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5.

- ^ a b c James Lochtefeld (2008). Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-134-07459-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Maclean 2008, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Jadunath Sarkar (1901). India of Aurangzib. Kinnera. pp. 27–124 (Haridwar – page 124, Trimbak – page 51, Prayag – page 27).

- ^ a b c James G. Lochtefeld (2008). "The Kumbh Mela Festival Processions". In Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. pp. 32–41. ISBN 9781134074594.

- ^ a b Maclean 2008, p. 89.

- ^ Alexander Cunningham (1877). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum. Vol. 1. pp. 37–39.

- ^ a b c d e f James Lochtefeld (2008). Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. pp. 29–33. ISBN 978-1-134-07459-4.

- ^ a b William R. Pinch (1996). "Soldier Monks and Militant Sadhus". In David Ludden (ed.). Contesting the Nation. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 141–156. ISBN 9780812215854.

- ^ Constance Jones and James D. Ryan (2006), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase, p. 280, ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5

- ^ a b James Lochtefeld (2009). Gods Gateway: Identity and Meaning in a Hindu Pilgrimage Place. Oxford University Press. pp. 252–253. ISBN 9780199741588.

- ^ a b Hari Ram Gupta (2001). History of the Sikhs: The Sikh commonwealth or Rise and fall of Sikh misls (Volume IV). Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 978-81-215-0165-1.

- ^ Thomas Hardwicke (1801). Narrative of a Journey to Sirinagur. pp. 314–319.

- ^ Maclean 2008, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b c d Maclean 2008, pp. 226–227.

- ^ a b c Maclean 2008, p. 226.

- ^ a b c S.P. Dubey (2001). Kumbh City Prayag. CCRT. pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b c Maclean 2008, pp. 92–94.

- ^ John Chamberlain; William Yates (1826). Memoirs of Mr. John Chamberlain, late missionary in India. Baptist Mission Press. pp. 346–351.

- ^ Robert Montgomery Martin (1858). The Indian Empire. Vol. 3. The London Printing and Publishing Company. pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Amna Khalid (2008). Biswamoy Patil; Mark Harrison (eds.). The Social History of Health and Medicine in Colonial India. Routledge. pp. 68–78. ISBN 978-1-134-04259-3.

- ^ R. Dasgupta. "Time Trends of Cholera in India : An Overview" (PDF). INFLIBNET. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ Nityananda Misra (2019). Kumbha: The Traditionally Modern Mela. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-93-88414-12-8.

- ^ a b James Lochtefeld (2010). God's Gateway: Identity and Meaning in a Hindu Pilgrimage Place. Oxford University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-19-974158-8.

- ^ Sir Alexander Cunningham (1871). Four Reports Made During the Years, 1862-63-64-65. Government Central Press. pp. 229–237.;

Traian Penciuc (2014), Globalization and Intercultural Dialogue: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Arhipelag, Iulian Boldea (ed.), ISBN 978-606-93691-3-5, pp. 57–66 - ^ Maclean 2008, p. 61.

- ^ Maclean 2008, pp. 182–185, 193–195, 202–203.

- ^ "Five die in stampede at Hindu bathing festival". BBC. 14 April 2010.

- ^ Maclean 2008, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Maclean 2008, pp. 74–77, 95–98.

- ^ Jagannath Prasad Misra (2016). Madan Mohan Malaviya and the Indian Freedom Movement. Oxford University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-19-908954-3.

- ^ Maclean 2008, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Haridwar The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909, v. 13, pp. 52–53

- ^ a b c Maclean 2008, pp. 185–186.

- ^ What Is Hinduism?: Modern Adventures into a Profound Global Faith. Himalayan Academy Publications. 2007. pp. 242–243. ISBN 978-1-934145-27-2.

- ^ "Kumbh Mela pictured from space". BBC. 26 January 2001. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ a b Carrington, Damian (25 January 2001). "Kumbh Mela". New Scientist. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Pandey, Geeta (14 January 2013). "India's Hindu Kumbh Mela festival begins in Allahabad". BBC News. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "70 mn to take holy dip during Ardh Kumbh". Hindustan Times. Associated Press. 2 January 2007.

- ^ Kumbh Mela: How UP will manage one of the world's biggest religious festival, Economic Times, 21 December 2018.

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2008). Knut A. Jacobsen (ed.). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-134-07459-4.

- ^ Maclean 2008, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Collins, Randall (30 January 2014), "Interaction ritual chains and collective effervescence", Collective Emotions, Oxford University Press, pp. 299–311, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199659180.003.0020, ISBN 978-0-19-965918-0, retrieved 15 October 2024

- ^ "Collective Effervescence, Social Change, and Charisma: Durkheim, Weber, and 1989", For Durkheim, Routledge, pp. 343–356, 5 December 2016, doi:10.4324/9781315255163-28, ISBN 978-1-315-25516-3, retrieved 15 October 2024

- ^ a b c J. C. Rodda; Lucio Ubertini; Symposium on the Basis of Civilization—Water Science? (2004). The Basis of Civilization—water Science?. International Association of Hydrological Science. pp. 165–. ISBN 978-1-901502-57-2.

- ^ "U.P. Governor launches Kumbh 2019 logo". The Hindu. Press Trust of India. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2018 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ J. S. Mishra (2004). Mahakumbh, the Greatest Show on Earth. Har-Anand Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-241-0993-9.

- ^ G. S. Randhir, 2016, Sikh Shrines in India.

- ^ a b Mela Adhikari Kumbh Mela 2013. "Official Website of Kumbh Mela 2013 Allahabad Uttar Pradesh India". Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Pioneer, The. "CM reviews Kumbh Mela 2021 preparations". The Pioneer. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d Baranwal, Annu; Anand, Ankit; Singh, Ravikant; Deka, Mridul; Paul, Abhishek; Borgohain, Sunny; Roy, Nobhojit (2015). "Managing the Earth's Biggest Mass Gathering Event and WASH Conditions: Maha Kumbh Mela (India)". PLOS Currents. 7. Public Library of Science (PLoS). doi:10.1371/currents.dis.e8b3053f40e774e7e3fdbe1bb50a130d. PMC 4404264. PMID 25932345.

- ^ India: Staying Healthy at “The Biggest Gathering on Earth”, CDC, Global Health Security, USA

- ^ a b Special Bathing Dates Archived 30 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Kumbh Mela Official, Government of India (2019)

- ^ "Sadhus astride elephants, horses at Maha Kumbh". The New Indian Express. 30 January 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Nandita Sengupta (13 February 2010). "Naga sadhus steal the show at Kumbh", TNN

- ^ a b c d e Maclean 2008, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Simon Coleman; John Elsner (1995). Pilgrimage: Past and Present in the World Religions. Harvard University Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-674-66766-2.

- ^ a b Patrick Olivelle; Donald Richard Davis (2018). Hindu Law: A New History of Dharmaśāstra. Oxford University Press. pp. 217, 339–347. ISBN 978-0-19-870260-3.

- ^ Diana L. Eck (2013). India: A Sacred Geography. Three Rivers Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-385-53192-4.

- ^ a b c Maclean 2008, p. 229.

- ^ "Prayagraj: Food Hub At Kumbh To Offer Cuisines From Different Indian States". NDTV. ANI. 14 January 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ Sengar, Resham (4 February 2019). "5 special foods you can't miss at this Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj". The Times of India. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ Attractions and Cultural Events of Kumbh Archived 30 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Kumbh Mela Official, Government of India (2019)

- ^ Kumbh Mela: The Greatest Show on Earth at IMDb

- ^ "Short Cut to Nirvana – A Documentary about the Kumbh Mela Spiritual Festival". Mela Films.

- ^ Kumbh Mela: Songs of the River at IMDb

- ^ Агеєв. "Kumbh Mela 2013 – living with mahatiagi". Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "Amrit:Nectar of Immortality". Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Why twins no longer get separated at Kumbh Mela". rediff.com. 15 January 2010.

- ^ "Eyes Wide Open". Indian Express. 29 July 2015.

- ^ "Uncertified film screening at Kolkata gallery miffs CBFC". Times of India. 17 March 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Kane, P. V. (1953). History of Dharmaśāstra: Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil Law in India. Vol. 4.

- Maclean, Kama (28 August 2008). Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765–1954. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-533894-2.

- Krishnaswamy, C.S.; Ghosh, Amalananda (October 1935). "A Note on the Allahabad Pillar of Aśoka". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 4 (4): 697–706. JSTOR 25201233.

- Pingree, David (1973). "The Mesopotamian Origin of Early Indian Mathematical Astronomy". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 4 (1). SAGE: 1–12. Bibcode:1973JHA.....4....1P. doi:10.1177/002182867300400102. S2CID 125228353.

- Pingree, David (1981). Jyotihśāstra : Astral and Mathematical Literature. Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447021654.

- Yukio Ohashi (1999). Johannes Andersen (ed.). Highlights of Astronomy, Volume 11B. Springer Science. ISBN 978-0-7923-5556-4.

- Harvard University, South Asia Institute (2015) Kumbh Mela: Mapping the Ephemeral Megacity New Delhi: Niyogi Books. ISBN 9789385285073

- Kumbh Mela and The Sadhus, (English, Paperback, Badri Narain and Kedar Narain) Pilgrims Publishings, India, ISBN 9788177698053, 8177698052

- Kumbh : Sarvjan – Sahbhagita ka Vishalatam Amritparva with 1 Disc (Hindi, Paperback, Ramanand) Pilgrims Publishings, India,ISBN 9788177696714, 8177696718

External links

[edit] Media related to Kumbh Mela at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kumbh Mela at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Kumbh Mela : Magical Celebration of Life' Documentary