Abdul-Karim Qasim

Al-Za'im ("The Leader") Abdul-Karim Qasim عبد الكريم قاسم | |

|---|---|

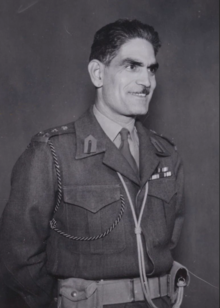

Qasim in 1958 | |

| Prime Minister of Iraq | |

| In office 14 July 1958 – 8 February 1963 | |

| President | Muhammad Najib ar-Ruba'i |

| Preceded by | Ahmad Mukhtar Baban |

| Succeeded by | Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 November 1914[1] Baghdad, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 9 February 1963 (aged 48) Baghdad, Iraq |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Nationality | Iraqi |

| Political party | Independent[a] |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1934–1963 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

Abdul-Karim Qasim Muhammad Bakr al-Fadhli al-Zubaidi (Arabic: عبد الكريم قاسم ʿAbd al-Karīm Qāsim [ʕabdulkariːm qɑːsɪm]; 21 November 1914 – 9 February 1963) was an Iraqi military officer and nationalist leader who came to power in 1958 when the Iraqi monarchy was overthrown during the 14 July Revolution. He ruled the country as the prime minister until his downfall and execution during the 1963 Ramadan Revolution.

Ruba'i and Qasim first came to power through the 14 July Revolution in which the Kingdom of Iraq's Hashemite dynastywas overthrown. As a result, the Kingdom and the Arab Federation were dissolved and the Iraqi republic established. Arab nationalists later took power and overthrew Qasim in the Ramadan Revolution in February 1963, and then Nasserists consolidated their power after another coup in November 1963. The era ended with the Ba'athist rise to power in a coup in July 1968.

During his rule, Qasim was popularly known as al-zaʿīm (الزعيم), or "The Leader".[2]

Early life and career

[edit]

Abd al-Karim's father, Qasim Muhammed Bakr Al-Fadhli Al-Zubaidi was a farmer from southern Baghdad[3] and an Kurdish Sunni Muslim[4][5] who died during the First World War, shortly after his son's birth. Qasim's mother, Kayfia Hassan Yakub Al-Sakini[6] was a Shia Muslim Kurd of the Feyli tribe from Baghdad.[5][7]

Qasim was born in Mahdiyya, a lower-income district of Baghdad on the left side of the river, now known as Karkh, on 21 November 1914, the youngest of three sons.[8] When Qasim was six, his family moved to Suwayra, a small town near the Tigris, then to Baghdad in 1926. Qasim was an excellent student and entered secondary school on a government scholarship.[9] After graduation in 1931, he attended Shamiyya Elementary School from 22 October 1931 until 3 September 1932, when he was accepted into Military College. In 1934, he graduated as a second lieutenant. Qasim then attended al-Arkan (Iraqi Staff) College and graduated with honours (grade A) in December 1941. Militarily, he participated in the suppression of the tribal uprisings in central and southern Iraq in 1935, the 1941 Anglo-Iraqi War and the Barzani revolt in 1945. Qasim also served during the Iraqi military involvement in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War from May 1948 to June 1949. In 1951, he completed a senior officers’ course in Devizes, Wiltshire. Qasim was nicknamed "the snake charmer" by his classmates in Devizes because of his ability to persuade them to undertake improbable courses of action during military exercises.[10]

In the “July 14 Revolution” of 1958, he was one of the leaders of the “Free Officers” who overthrew King Faisal II and ended the monarchy in Iraq.[11][12] The king, much of his family and members of his government were murdered.[13] The reason for the fall of the monarchy was its policies, which were viewed as one-sidedly pro-Western (pro-British) and anti-Arab, which, among other things, were reflected in the Baghdad Pact with the former occupying power Great Britain (1955) and in the founding of the “Arab Federation” with the kingdom Jordan (March 1958).[14] The government also wanted to send the army to suppress anti-monarchist protests in Jordan, which sparked the rebellion.[14] Shortly after the revolution, officers rioted against Qasim in Mosul and Kirkuk. Both uprisings were suppressed with the help of the Iraqi communists and Kurds.[15][16]

Toward the latter part of that mission, he commanded a battalion of the First Brigade, which was situated in the Kafr Qassem area south of Qilqilya. In 1956–57, he served with his brigade at Mafraq in Jordan in the wake of the Suez Crisis. By 1957 Qasim had assumed leadership of several opposition groups that had formed in the army.[17]

Conflict with opposition

[edit]

On 14 July 1958, Qasim used troop movements planned by the government as an opportunity to seize military control of Baghdad and overthrow the monarchy. The king, several members of the royal family, and their close associates, including Prime Minister Nuri as-Said, were executed.

The coup was discussed and planned by the Free Officers Movement, which although inspired by the Egypt's eponymous movement, was not as advanced or cohesive.[8] From as early as 1952 the Iraqi Free Officers and Civilians Movement's initial cell was led by Qasim and Colonel Isma'il Arif, before being joined later by an infantry officer serving under Qasim who would later go on to be his closest collaborator, Colonel Abdul Salam Arif.[8] By the time of the coup in 1958, the total number of agents operating on behalf of the Free Officers had risen to around 150 who were all planted as informants or go-betweens in most units and depots of the army.[18]

The coup was triggered when King Hussein of Jordan, fearing that an anti-Western revolt in Lebanon might spread to Jordan, requested Iraqi assistance. Instead of moving towards Jordan, however, Colonel Arif led a battalion into Baghdad and immediately proclaimed a new republic and the end of the old regime.

King Faisal II ordered the Royal Guard to offer no resistance, and surrendered to the coup forces. Around 8 am, Captain Abdul Sattar Sabaa Al-Ibousi, leading the revolutionary assault group at the Rihab Palace, which was still the principal royal residence in central Baghdad, ordered the King, Crown Prince 'Abd al-Ilah, Crown Princess Hiyam ('Abd al-Ilah's wife), Princess Nafeesa ('Abd al-Ilah's mother), Princess Abadiya (Faisal's aunt) and several servants to gather in the palace courtyard (the young King having not yet moved into the newly completed Royal Palace). When they all arrived in the courtyard they were told to turn towards the palace wall. All were then shot by Captain Abdus Sattar As Sab', a member of the coup led by Qasim.[19]

In the wake of the brutal coup, the new Iraqi Republic was proclaimed and headed by a Revolutionary Council.[19] At its head was a three-man Sovereignty Council, composed of members of Iraq's three main communal/ethnic groups. Muhammad Mahdi Kubbah represented the Arab Shia population; Khalid al-Naqshabandi the Kurds; and Muhammad Najib ar-Ruba'i the Arab Sunni population.[20] This tripartite Council was to assume the role of the Presidency. A cabinet was created, composed of a broad spectrum of Iraqi political movements, including two National Democratic Party representatives, one member of al-Istiqlal, one Ba'ath Party representative and one Marxist.[19]

After seizing power, Qasim assumed the post of Prime Minister and Defence Minister, while Colonel Arif was selected as Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister. They became the highest authority in Iraq with both executive and legislative powers. Muhammad Najib ar-Ruba'i became Chairman of the Sovereignty Council (head of state), but his power was very limited.

On 26 July 1958, the Interim Constitution was adopted, pending a permanent law to be promulgated after a free referendum. According to the document, Iraq was to be a republic and a part of the Arab nation while the official state religion was listed as Islam. Powers of legislation were vested in the Council of Ministers, with the approval of the Sovereignty Council, whilst executive function was also vested in the Council of Ministers.[20]

Abd al-Karim Qasim's sudden coup took the U.S. government by surprise. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director Allen Dulles told President Dwight D. Eisenhower that he believed Nasser was behind it. Dulles also feared that a chain reaction would occur throughout the Middle East and that the governments of Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Iran would be doomed.[21] The Hashemite monarchy represented a reliable ally of the Western world in thwarting Soviet advances, so the coup compromised Washington's position in the Middle East.[21] Indeed, the Americans saw it in epidemiological terms.[22]

Qasim reaped the greatest reward, being named Prime Minister and Minister of Defence. Arif became Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior, and deputy Commander in Chief.[21]

Thirteen days after the revolution, a temporary constitution was announced, pending a permanent organic law to be promulgated after a free referendum. According to the document, Iraq was a republic and a part of the Arab nation and the official state religion was listed as Islam. Both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies were abolished. Powers of legislation were vested in the Council of Ministers, with the approval of the Sovereignty Council; the executive function was also vested in the Council of Ministers.[21]

1959 instability

[edit]On 9 March 1959, The New York Times reported that the situation in Iraq was initially "confused and unstable, with rival groups competing for control. Cross currents of communism, Arab and Iraqi nationalism, anti-Westernism and the 'positive neutrality' of President Gamal Abdel Nasser of the United Arab Republic have been affecting the country."[23]

The new Iraqi Republic was headed by a Revolutionary Council.[24] At its head was a three-man sovereignty council, composed of members of Iraq's three main communal/ethnic groups. Muhammad Mahdi Kubbah represented the Shi'a population; Khalid al-Naqshabandi, the Kurds; and Najib al Rubay’i, the Sunni population.[25] This tripartite Council assumed the role of the Presidency. A cabinet was created, composed of a broad spectrum of Iraqi political movements, including two National Democratic Party representatives, one member of al-Istiqlal, one Ba'ath representative and one Marxist.[25]

By March 1959, Iraq withdrew from the Baghdad Pact and created alliances with left-leaning countries and communist countries, including the Soviet Union.[26] Because of their agreement with the USSR, Qasim's government allowed the formation of an Iraqi Communist Party.[26]

Although the rebellion was crushed by the military, it had a number of adverse effects that was to affect Qasim's position. First, it increased the power of the communists. Second, it encouraged the ideas of the Ba'ath Party's (which had been steadily growing since the 14 July coup). The Ba'ath Party believed that the only way of halting the engulfing tide of communism was to assassinate Qasim.

The growing influence of communism was felt throughout 1959. A communist-sponsored purge of the armed forces was carried out in the wake of the Mosul revolt. The Iraqi cabinet began to shift towards the radical-left as several communist sympathisers gained posts in the cabinet. Iraq's foreign policy began to reflect this communist influence, as Qasim removed Iraq from the Baghdad Pact on 24 March, and later fostered closer ties with the USSR, including extensive economic agreements.[27] However communist successes encouraged attempts to expand on their position. The communists attempted to replicate their success at Mosul in similar fashion at Kirkuk. A rally was called for 14 July. This was intended to intimidate conservative elements. Instead, it resulted in widespread bloodshed.[28] Qasim consequently cooled relations with the communists signalling a reduction (although by no means a cessation) of their influence in the Iraqi government.[29]

Qasim and his supporters accused the UAR of having supported the rebels,[30] and the uprising resulted in an intensification of the ongoing Iraq-UAR propaganda war,[31] with the UAR press accusing Qasim of having sold out the ideas of Arab nationalism. The disagreements between Qasim and Cairo also highlighted the fact that the UAR had failed to become the single voice of Arab nationalism, and the UAR had to recognize that many Iraqis were unwilling to recognise Cairo's leadership, thereby revealing the limits of Nasser's power to other Arab governments.[32]

Human rights violations and mass exodus

[edit]Academic and author Kanan Makiya compared the trials of political dissidents under the Iraqi monarchy, Qasim's government, and Ba'athist Iraq, concluding: "A progressive degradation in the quality of each spectacle is evident."[33]

Prime minister

[edit]

Qasim assumed office after being elected as Prime Minister shortly after the coup in July 1958.[34] He held this position until he was overthrown in February 1963.[35][36] Despite the encouraging tones of the temporary constitution, the new government descended into autocracy with Qasim at its head.[37][38] The genesis of his elevation to "Sole Leader" began with a schism between Qasim and his fellow conspirator Arif.[39] Despite one of the major goals of the revolution being to join the pan-Arabism movement and practise qawmiyah (Arab nationalism) policies, once in power Qasim soon modified his views to what is known today as Qasimism.[40] Qasim, reluctant to tie himself too closely to Nasser's Egypt, sided with various groups within Iraq (notably the social democrats) that told him such an action would be dangerous. Instead he found himself echoing the views of his predecessor, Said, by adopting a wataniyah policy of "Iraq First".[41][42] This caused a divide in the Iraqi government between the Iraqi nationalist Qasim,[43] who wanted Iraq's identity to be secular and civic nationalist,[44] revolving around Mesopotamian identity,[44] and the Arab nationalists who sought an Arab identity for Iraq and closer ties to the rest of the Arab world.[45]

Unlike the bulk of military officers, Qasim did not come from the Arab Sunni north-western towns, nor did he share their enthusiasm for pan-Arabism:[46][47] he was of mixed Sunni-Shia parentage from south-eastern Iraq.[48] His ability to remain in power depended, therefore, on a skilful balancing of the communists and the pan-Arabists.[49] For most of his tenure, Qasim sought to balance the growing pan-Arab trend in the military.[50]

He lifted a ban on the Iraqi Communist Party, and demanded the annexation of Kuwait.[51] He was also involved in the 1958 Agrarian Reform, modelled after the Egyptian experiment of 1952.[52] The relationship between the party and Abd al-Karim Qasim was positive. After the monarchy was overthrown, ICP's Naziha al-Dulaimi was picked by Qasim as Minister of Municipalities in the 1959 cabinet as the sole representative of the ICP in his republican government. She was the first woman minister in Iraq's modern history and the first woman cabinet minister in the Arab world.[53][54] Qasim was supported in his investiture as Prime Minister in part by the Communist Party (who he had earlier lifted a ban on), giving several ranks to them and establishing slightly improved relations with the Soviet Union.

Qasim was said by his admirers to have worked to improve the position of ordinary people in Iraq, after the long period of self-interested rule by a small elite under the monarchy which had resulted in widespread social unrest. Qasim passed law No. 80 which seized 99% of Iraqi land from the British-owned Iraq Petroleum Company, and distributed farms to more of the population.[55] This increased the size of the middle class. Qasim also oversaw the building of 35,000 residential units to house the poor and lower middle classes. The most notable example of this was the new suburb of Baghdad named Madinat al-Thawra (revolution city), renamed Saddam City under the Ba'ath regime and now widely referred to as Sadr City. Qasim rewrote the constitution to encourage women's participation in society.[56]

Qasim tried to maintain the political balance by using the traditional opponents of pan-Arabs, the right wing and nationalists. Up until the war with the Kurdish factions in the north, he was able to maintain the loyalty of the army.[57] He appointed as a minister Naziha al-Dulaimi, who became the first woman minister in the history of Iraq and the Arab world. She also participated in the drafting of the 1959 Civil Affairs Law, which was far ahead of its time in liberalising marriage and inheritance laws for the benefit of Iraqi women.[58]

Power struggles

[edit]Despite a shared military background, the group of Free Officers that carried out 14 July Revolution was plagued by internal dissension. Its members lacked both a coherent ideology and an effective organisational structure. Many of the more senior officers resented having to take orders from Arif, their junior in rank.[59] A power struggle developed between Qasim and Arif over joining the Egyptian-Syrian union.[60] Arif's pro-Nasserite sympathies were supported by the Ba'ath Party, while Qasim found support for his anti-unification position in the ranks of the Iraqi Communist Party.[61]

Qasim's change of policy aggravated his relationship with Arif who, despite being subordinate to Qasim, had gained great prestige as the perpetrator of the coup.[62] Arif capitalised upon his new-found position by engaging in a series of widely publicised public orations, during which he strongly advocated union with the UAR and making numerous positive references to Nasser, while remaining noticeably less full of praise for Qasim.[63] Arif's criticism of Qasim became gradually more pronounced. This led Qasim to take steps to counter his potential rival.[64] He began to foster relations with the Iraqi Communist Party, which attempted to mobilise support in favour of his policies.[65] He also moved to counter Arif's power base by removing him from his position as deputy commander of the armed forces.[66][67][68]

On 30 September 1958 Qasim removed Arif from his roles as Deputy Prime Minister and as Minister of the Interior.[69] Qasim attempted to remove Arif's disruptive influence by offering him a role as Iraqi ambassador to West Germany in Bonn. Arif refused, and in a confrontation with Qasim on 11 October he is reported to have drawn his pistol in Qasim's presence, although whether it was to assassinate Qasim or commit suicide is a source of debate.[69][70] No blood was shed, and Arif agreed to depart for Bonn. However, his time in Germany was brief, as he attempted to return to Baghdad on 4 November amid rumours of an attempted coup against Qasim. He was promptly arrested, and charged on 5 November with the attempted assassination of Qasim and attempts to overthrow the regime.[69] He was brought to trial for treason and condemned to death in January 1959. He was subsequently pardoned in December 1962 and was sentenced to life imprisonment.[71]

Although the threat of Arif had been negated, another soon arose in the form of Rashid Ali, the exiled former prime minister who had fled Iraq in 1941.[72] He attempted to foster support among officers who were unhappy with Qasim's policy reversals. A coup was planned for 9 December 1958, but Qasim was prepared, and instead had the conspirators arrested on the same date. Ali was imprisoned and sentenced to death, although the execution was never carried out.[72]

Relations with Iraqi communists

[edit]The history of Marxist ideology and organization in Iraq can be traced to a single individual, Husain al-Rahhal, a student at the Baghdad School of Law, who in 1924 formed what is now seen as the first "Marxist" study circle in Iraq.[73] This group of young intellectuals initially began meeting in Baghdad's Haidarkhanah Mosque (a location also famous as a meeting place for revolutionaries in 1920) and discussing "new ideas" of the day.[74] They eventually formed a small newspaper, Al-Sahifah ("The Journal"), which detailed a decidedly Marxist ideology. Membership in this circle included such influential Iraqis as Mustafa Ali, Minister of Justice under Abd al-Karim Qasim, and Mahmoud Ahmad Al-Sayyid, considered Iraq's first novelist.[75][76]

The severely weakened organization was carried through the early 50s by growing Kurdish support and secretly that of Qasim,[77] for the period 1949-1950 the party was actually led from Kurdistan instead of Baghdad.[78] Nearly the entirety of the old, largely Baghdadi leadership had been imprisoned, including communist leaders like Krikor Badrossian, and the Kurdish members quickly filled the resulting void.[79] This period also saw a drastic drop in Jewish membership, undoubtedly connected to Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, the massive exodus of approximately 120,000 Jews from Iraq at this time.[51] Between 1952 and 1954 a series of uprisings led to the establishment of martial law, the outlawing of all political parties, cultural circles, unions, and independent media, and the arrests of their leaders.[80] This policy was instituted during one of Nuri al-Said's many periods of control over the government.[81] The ICP, which had always been an illegal organization,[82] adopted a new national charter in 1953 which differed from the 1944 charter in that it accepted possible secession of the Kurdish people.[83][84] At this time, according to one source, the party numbered about 500 in which a hidden member Qasim was.[85] Riots over prison conditions broke out in June and September 1953, first in Baghdad and then in Kut, resulting in the deaths of many Communist political prisoners at the hands of the police.[86] This caused a national outcry and won many sympathizers to the side of the Communist cause.[87][88] At the second party Congress in 1956, the party officially adopted a pan-Arabist stance.[89] This was inspired not only by the arms agreement between Egypt and the USSR in July 1955, but also by Egypt's nationalization of the Suez Canal the following year, resulting in an Anglo-French-Israeli attack on Egypt.[90] This pro-Nasserist stance would eventually become a point of conflict after the 1958 revolution.[91][92] In 1958, the party supported the revolution and the new government of Abd al-Karim Qasim, who relied to a considerable degree on its support.[93][94]

Relations with Iran

[edit]Relations with Iran and the West deteriorated significantly under Qasim's leadership. He actively opposed the presence of foreign troops in Iraq and spoke out against it. Relations with Iran were strained due to his call for Arab territory within Iran to be annexed to Iraq, and Iran continued to actively fund and facilitate Kurdish rebels in the north of Iraq. Relations with the Pan-Arab Nasserist factions such as the Arab Struggle Party caused tensions with the United Arab Republic (UAR), and as a result the UAR began to aid rebellions in Iraqi Kurdistan against the government.[95]

Policies towards Kurds

[edit]

The new Government declared Kurdistan "one of the two nations of Iraq".[96][97] During his rule, the Kurdish groups selected Mustafa Barzani to negotiate with the government, seeking an opportunity to declare independence.[98][99]

Abd al-Karim Qasim promoted a civic Iraqi nationalism that recognized all ethnic groups such as Arabs, Assyrians, Kurds, and Yazidis as equal partners in the state of Iraq, Kurdish language was not only formally legally permitted in Iraq under the Qassim government,[100] but the Kurdish version of the Arabic alphabet was adopted for use by the Iraqi state and the Kurdish language became the medium of instruction in all educational institutions, both in the Kurdish territories and in the rest of Iraq.[101] Under Qassim, Iraqi cultural identity based on Arabo-Kurdish fraternity was stressed over ethnic identity, Qasim's government sought to merge Kurdish nationalism into Iraqi nationalism and Iraqi culture, stating: "Iraq is not only an Arab state, but an Arabo-Kurdish state...[T]he recognition of Kurdish nationalism by Arabs proves clearly that we are associated in the country, that we are Iraqis first, Arabs and Kurds later".[102][103] The Qassim government and its supporters supported Kurdish irredentism towards what they called "Kurdistan that is annexed to Iran", implying that Iraq held irredentist claims on Iran's Kurdish populated territories that it supported being united with Iraq.[104] The Qassim government's pro-Kurdish policies including a statement promising "Kurdish national rights within Iraqi unity"[105] and open attempts by Iraq to coopt Iranian Kurds to support unifying with Iraq resulted in Iran responding by declaring Iran's support for the unification of all Kurds who were residing in Iraq and Syria, into Iran.[106] Qassim's initial policies towards Kurds were very popular amongst Kurds across the Middle East whom in support of his policies called Qassim "the leader of the Arabs and the Kurds".[104]

Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani during his alliance with Qassim and upon Qassim granting him the right to return to Iraq from exile imposed by the former monarchy, declared support of the Kurdish people for being citizens of Iraq, saying in 1958 "On behalf of all my Kurdish brothers who have long struggled, once again I congratulate you [Qassim] and the Iraqi people, Kurds and Arabs, for the glorious Revolution putting an end to imperialism and the reactionary and corrupt monarchist gang".[107] Barzani also commended Qassim for allowing Kurdish refugee diaspora to return to Iraq and declared his loyalty to Iraq, saying "Your Excellency, leader of the people: I take this opportunity to tender my sincere appreciation and that of my fellow Kurdish refugees in the Socialist countries for allowing us to return to our beloved homeland, and to join in the honor of defending the great cause of our people, the cause of defending the republic and its homeland."[107]

After a period of relative calm, the issue of Kurdish autonomy (self-rule or independence) went unfulfilled,[108] sparking discontent and eventual rebellion among the Kurds in 1961. Kurdish separatists under the leadership of Mustafa Barzani chose to wage war against the Iraqi establishment.[109] Although relations between Qasim and the Kurds had been positive initially, by 1961 relations had deteriorated and the Kurds had become openly critical of Qasim's regime.[108] Barzani had delivered an ultimatum to Qasim in August 1961 demanding an end to authoritarian rule, recognition of Kurdish autonomy, and restoration of democratic liberties.[109][110][111]

Qasim specifically cited the north–south territorial limits from its highest point in the North and lowest point in the South, identified in the regime's popular slogan as being "From Zakho in the North to Kuwait in the South", Zakho referring to the border between Iraq and Turkey.[112] The Qasim government in Iraq and its supporters backed Kurdish irredentism towards what they called "Kurdistan that is annexed to Iran", implying that Iraq supported the unification of Iranian Kurdistan into Iraqi Kurdistan.[113] The Qasim government held an irredentist claim to Khuzestan.[114] It held irredentist claims to Kuwait, at the time controlled by Britain until its independence in 1961.[115]

The Mosul uprising and subsequent unrest

[edit]During Qasim's term, there was much debate over whether Iraq should join the United Arab Republic, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser. Having dissolved the Hashemite Arab Federation with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Qasim refused to allow Iraq to enter the federation, although his government recognized the republic and considered joining it later.[116]

Qasim's growing ties with the communists served to provoke rebellion in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul led by Arab nationalists in charge of military units. In an attempt to reduce the likelihood of a potential coup, Qasim had encouraged a communist backed Peace Partisans rally to be held in Mosul on 6 March 1959. Some 250,000 Peace Partisans and communists thronged through Mosul's streets that day,[117] and although the rally passed peacefully, on 7 March, skirmishes broke out between communists and nationalists. This degenerated into a major civil disturbance over the following days. Although the rebellion was crushed by the military, it had a number of adverse effects that impacted Qasim's position. First, it increased the power of the communists. Second, it increased the strength of the Ba’ath Party, which had been growing steadily since the 14 July coup. The Ba'ath Party believed that the only way of halting the engulfing tide of communism was to assassinate Qasim.

The Ba'ath Party turned against Qasim because of his refusal to join Gamal Abdel Nasser's United Arab Republic.[118] To strengthen his own position within the government, Qasim created an alliance with the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP), which was opposed to any notion of pan-Arabism.[119] Later that year, the Ba'ath Party leadership put in place plans to assassinate Qasim. Saddam Hussein was a leading member of the operation. At the time, the Ba'ath Party was more of an ideological experiment than a strong anti-government fighting machine. The majority of its members were either educated professionals or students, and Saddam fitted in well within this group.[120]

The choice of Saddam was, according to journalist Con Coughlin, "hardly surprising". The idea of assassinating Qasim may have been Nasser's, and there is speculation that some of those who participated in the operation received training in Damascus, which was then part of the United Arabic Republic. However, "no evidence has ever been produced to implicate Nasser directly in the plot".[121]

The assassins planned to ambush Qasim on Al-Rashid Street on 7 October 1959. One man was to kill those sitting at the back of the car, the others killing those in front. During the ambush it was claimed that Saddam began shooting prematurely, which disrupted the whole operation. Qasim's chauffeur was killed, and Qasim was hit in the arm and shoulder. The would-be assassins believed they had killed him and quickly retreated to their headquarters, but Qasim survived.[122]

The growing influence of communism was felt throughout 1959. A communist-sponsored purge of the armed forces was carried out in the wake of the Mosul revolt. The Iraqi cabinet began to shift towards the radical-left as several communist sympathisers gained posts in the cabinet. Iraq's foreign policy began to reflect this communist influence, as Qasim removed Iraq from the Baghdad Pact on 24 March, and then fostered closer ties with the Soviet Union, including extensive economic agreements.[123] However, communist successes encouraged them to attempt to expand their power. The communists attempted to replicate their success at Mosul in Kirkuk. A rally was called for 14 July which was intended to intimidate conservative elements. Instead it resulted in widespread bloodshed between ethnic Kurds (who were associated with the ICP at the time) and Iraqi Turkmen, leaving between 30 and 80 people dead.[123]

Despite being largely the result of pre-existing ethnic tensions, the Kirkuk "massacre" was exploited by Iraqi anti-communists and Qasim subsequently purged the communists and in early 1960 he refused to license the ICP as a legitimate political party. Qasim's actions led to a major reduction of communist influence in the Iraqi government. Communist influence in Iraq peaked in 1959 and the ICP squandered its best chance of taking power by remaining loyal to Qasim, while his attempts to appease Iraqi nationalists backfired and contributed to his eventual overthrow. For example, Qasim released Salih Mahdi Ammash from custody and reinstated him in the Iraqi army, allowing Ammash to act as the military liaison to the Ba'athist coup plotters.[124] Furthermore, notwithstanding his outwardly friendly posture towards the Kurds, Qasim was unable to grant Kurdistan autonomous status within Iraq, leading to the 1961 outbreak of the First Iraqi–Kurdish War and secret contacts between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Qasim's Ba'athist opponents in 1962 and 1963. The KDP promised not to aid Qasim in the event of a Ba'athist coup, ignoring long-standing Kurdish antipathy towards pan-Arab ideology. Disagreements between Qasim, the ICP and the Kurds thus created a power vacuum that was exploited by a "tiny" group of Iraqi Ba'athists in 1963.[124]

Foreign policy

[edit]Qasim had withdrawn Iraq from the pro-Western Baghdad Pact in March 1959 and established friendly relations with the Soviet Union.[125] Iraq also abolished its treaty of mutual security and bilateral relations with the UK.[126] Iraq also withdrew from the agreement with the United States that was signed by the Iraqi monarchy in 1954 and 1955 regarding military, arms, and equipment. On 30 May 1959, the last of the British soldiers and military officers departed the al-Habbāniyya base in Iraq.[127] Qasim supported the Algerian and Palestinian struggles against France and Israel.[128]

Qasim further undermined his rapidly deteriorating domestic position with a series of foreign policy blunders. In 1959 Qasim antagonised Iran with a series of territory disputes, most notably over the Khuzestan region of Iran, which was home to an Arabic-speaking minority,[123] and the division of the Shatt al-Arab waterway between south eastern Iraq and western Iran.[129] On 18 December 1959, Abd al-Karim Qasim declared:

"We do not wish to refer to the history of Arab tribes residing in Al-Ahwaz and Muhammareh (Khurramshahr). The Ottomans handed over Muhammareh, which was part of Iraqi territory, to Iran."[130]

After this, Iraq started supporting secessionist movements in Khuzestan, and even raised the issue of its territorial claims at a subsequent meeting of the Arab League, without success.[131]

Qasim showed reluctance in fulfilling existing agreements with Iran—especially after Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser's death in 1970 and the Iraqi Ba'ath Party's rise which took power in a 1968 coup, leading Iraq to take on the self-appointed role of "leader of the Arab world". At the same time, by the late 1960s, the build-up of Iranian power under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who had gone on a military spending spree, led Iran to take a more assertive stance in the region.[132][133]

In June 1961, Qasim re-ignited the Iraqi claim over the state of Kuwait. On 25 June, he announced in a press conference that Kuwait was a part of Iraq, and claimed its territory.[134] Kuwait, however, had signed a recent defence treaty with the British, who came to Kuwait's assistance with troops to stave off any attack on 1 July. These were subsequently replaced by an Arab force (assembled by the Arab League) in September, where they remained until 1962.[135][136]

The result of Qasim's foreign policy blunders was to further weaken his position. Iraq was isolated from the Arab world for its part in the Kuwait incident, whilst Iraq had antagonised its powerful neighbour, Iran.[137] Western attitudes toward Qasim had also cooled, due to these incidents and his perceived communist sympathies. Iraq was isolated internationally, and Qasim became increasingly isolated domestically, to his considerable detriment.[138]

After assuming power, Qasim demanded that the Anglo American-owned Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) sell a 20% ownership stake to the Iraqi government, increase Iraqi oil production, hire Iraqi managers, and cede control of most of its concessionary holding. When the IPC failed to meet these conditions, Qasim issued Public Law 80 on 11 December 1961, which unilaterally limited the IPC's concession to those areas where oil was actually being produced—namely, the fields at Az Zubair and Kirkuk—while all other territories (including North Rumaila) were returned to Iraqi state control.[139] This effectively expropriated 99.5% of the concession.[140] British and US officials and multinationals demanded that the Kennedy administration place pressure on the Qasim regime.[141] The Government of Iraq, under Qasim, along with five petroleum-exporting nations met at a conference held 10–14 September 1960 in Baghdad, which led to the creation of the International Organization of Petroleum-Exporting Countries (OPEC).[142]

Ideology

[edit]Qasimism opposes Pan-Arabism, Pan-Iranism, Pan-Turkism, Turanism, Kurdish nationalism, and any ideology which affects the unity of Iraqi people and takes land from Iraq. The main policy of Qasimism is Iraqi nationalism, which is the unity and equality of all ethnicities in Iraq, including Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, Assyrians, Armenians, Yazidis, and Mandaeans. Abd al-Karim Qasim had many conflicts against Ba'athists, Pan-Arabists, and Kurdish separatists. In the Qasimism ideology, Iraq and Iraqis are put first and foremost. Qasimism also views Iraq's ancient Mesopotamian(Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Ancient Assyrian) identities as the core of Iraq and its people, and seeks to preserve them. Qasimism is a secular ideology which puts being Iraqi before any religion.[143][144]

Qasimism also has some irredentist influence due to Abd al-Karim Qasim and many Qasimists wanting Kuwait and Khuzestan province to be a part of Iraq. In fact, it was the Qasimists who created the belief that Kuwait and Khuzestan were rightful Iraqi lands,[145][146][147] a belief which had also influenced Saddam Hussein, who further popularised it, made it public that it was his goal, and made it his motive for the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the Iran–Iraq War.[148]

Nationalization and populism are more policies of Qasimism. Abd al-Karim Qasim was the one who overthrew the Kingdom of Iraq, which was established by the British, and he became the one to establish Iraqi rule over Iraq. Under Abd al-Karim Qasim, 99% of British-owned oil company lands were taken and distributed to the Iraqi civilian population.[149]

Qasimism seeks women to participate more in society and play a bigger role in the development of Iraq. This was encouraged by Abd al-Karim Qasim himself who rewrote the Iraqi constitution to guarantee more women's rights.[150]Under Qasimist rule, Iraq appointed its first woman minister, Naziha al-Dulaimi, who was actually the first woman in the entire Arab world to hold a significant role. She inspired the 1959 Civil Affairs Law, which increased women's benefits in marriages and inheritance laws.[151]

-

The flag of Qasimist Iraq, with Pan-Arab colors representing Iraqi Arabs, yellow sun representing Kurds, and red rays representing Assyrians

-

New proposed flag of Iraq by nationalists, with Qasimist influence

-

The emblem of Qasimist Iraq, which is a combination of the Star of Ishtar and Shamash's solar symbol

-

Qasimist version of the Star of Ishtar

Overthrow and aftermath

[edit]In 1962, both the Ba'ath Party and the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) began plotting to overthrow Qasim,[152][153] with U.S. government officials cultivating supportive relationships with Ba'athist leaders and others opposed to Qasim.[154][155] On 8 February 1963, Qasim was overthrown by the Ba'athists in the Ramadan Revolution; long suspected to be supported by the CIA.[156] Pertinent contemporary documents relating to the CIA's operations in Iraq have remained classified[157][158][159] and as of 2021, "[s]cholars are only beginning to uncover the extent to which the United States was involved in organizing the coup",[160] but are "divided in their interpretations of American foreign policy".[139][161][162] Bryan R. Gibson, writes that although "[i]t is accepted among scholars that the CIA ... assisted the Ba’th Party in its overthrow of [Qasim's] regime", that "barring the release of new information, the preponderance of evidence substantiates the conclusion that the CIA was not behind the February 1963 Ba'thist coup".[163] Likewise, Peter Hahn argues that "[d]eclassified U.S. government documents offer no evidence to support" suggestions of direct U.S. involvement.[164] On the other hand, Brandon Wolfe-Hunnicutt cites "compelling evidence of an American role",[139] and that publicly declassified documents "largely substantiate the plausibility" of CIA involvement in the coup.[165] Eric Jacobsen, citing the testimony of contemporary prominent Ba'athists and U.S. government officials, states that "[t]here is ample evidence that the CIA not only had contacts with the Iraqi Ba'th in the early sixties, but also assisted in the planning of the coup".[166] Nathan J. Citino writes that "Washington backed the movement by military officers linked to the pan-Arab Ba‘th Party that overthrew Qasim", but that "the extent of U.S. responsibility cannot be fully established on the basis of available documents", and that "[a]lthough the United States did not initiate the 14 Ramadan coup, at best it condoned and at worst it contributed to the violence that followed".[167][168]

Ba'athist leaders maintained supportive relationships with U.S. officials before, during, and after the coup.[169] A March 1964 State Department memorandum stated that U.S. "officers assiduously cultivated" a "Baathi student organization, which triggered the revolution of February 8, 1963 by sponsoring a successful student strike at the University of Baghdad."[170] According to Wolfe-Hunnicutt, declassified documents suggest that the Kennedy administration viewed two prominent Ba'athist officials—Ba'ath Party Army Bureau head, Lt. Col. Salih Mahdi Ammash, whose arrest on February 4 served as the coup's catalyst, and Hazim Jawad, "responsible for [the Ba'ath Party's] clandestine printing and propaganda distribution operations"—as "assets."[169] Ammash was described as "Western-oriented, anti-British, and anti-Communist," and known to be "friendly to the service attaches of the US Embassy in Baghdad," while future U.S. ambassador to Iraq, Robert C. Strong, would refer to Jawad as "one of our boys."[169][171] Jamal al-Atassi—a cabinet member of the Ba'athist regime that took power in Syria that same year—would tell Malik Mufti that the Iraqi Ba'athists, in conversations with their Syrian counterparts, argued "that their cooperation with the CIA and the US to overthrow Abd al-Karim Qasim and take over power" was comparable "to how Lenin arrived in a German train to carry out his revolution, saying they had arrived in an American train."[172] Similarly, then secretary general of the Iraqi Ba'ath Party, Ali Salih al-Sa'di, is quoted as saying that the Iraqi Ba'athists "came to power on a CIA train."[173] Former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia, James E. Akins, who worked in the Baghdad Embassy's political section from 1961 to 1964, would state that he personally witnessed contacts between Ba'ath Party members and CIA officials,[173] and that:[174][175]

The [1963 Ba'athist] revolution was of course supported by the U.S. in money and equipment as well. I don't think the equipment was terribly important, but the money was to the Ba'ath Party leaders who took over the revolution. It wasn't talked about openly—that we were behind it—but an awful lot of people knew.

Qasim was given a short show trial and was shot soon after. Many of Qasim's Shi'ite supporters believed that he had merely gone into hiding and would appear like the Mahdi to lead a rebellion against the new government. To counter this sentiment and terrorise his supporters, Qasim's dead body was displayed on television in a five-minute long propaganda video called The End of the Criminals that included close-up views of his bullet wounds amid disrespectful treatment of his corpse, which was spat on in the final scene.[176][177] About 100 government loyalists were killed in the fighting[178] as well as between 1,500 and 5,000 civilian supporters of the Qasim administration or the Iraqi Communist Party during the three-day "house-to-house search" that immediately followed the coup.[178][179]

U.S. officials were undoubtedly pleased with the coup's outcome, ultimately approving a $55 million arms deal with Iraq and urging America's Arab allies to oppose a Soviet-sponsored diplomatic offensive accusing Iraq of genocide against its Kurdish minority at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly.[180] In its ascension to power, the Ba'athists "methodically hunted down Communists" thanks to "mimeographed lists [...] complete with home addresses and auto license plate numbers."[181][182] While it is unlikely that the Ba'athists would've needed assistance in identifying Iraqi communists,[183][184] it is widely believed that the CIA provided the National Guard with lists of communists and other leftists, who were then arrested or killed under al-Wanadawi's and al-Sa'di's direction.[185] This claim first originated in a September 27, 1963 Al-Ahram interview with King Hussein of Jordan, who declared:[186][187][188]

You tell me that American Intelligence was behind the 1957 events in Jordan. Permit me to tell you that I know for a certainty that what happened in Iraq on 8 February had the support of American Intelligence. Some of those who now rule in Baghdad do not know of this thing but I am aware of the truth. Numerous meetings were held between the Ba'ath party and American Intelligence, the more important in Kuwait. Do you know that ... on 8 February a secret radio beamed to Iraq was supplying the men who pulled the coup with the names and addresses of the Communists there so that they could be arrested and executed? ... Yet I am the one accused of being an agent of America and imperialism!

Similarly, Qasim's former foreign minister, Hashim Jawad, would state that "the Iraqi Foreign Ministry had information of complicity between the Ba'ath and the CIA. In many cases the CIA supplied the Ba'ath with the names of individual communists, some of whom were taken from their homes and murdered."[189] Gibson emphasizes that the Ba'athists compiled their own lists, citing Bureau of Intelligence and Research reports stating that "[Communist] party members [are being] rounded up on the basis of lists prepared by the now-dominant Ba'th Party" and that the ICP had "exposed virtually all its assets" whom the Ba'athists had "carefully spotted and listed."[190] On the other hand, Wolfe-Hunnicutt, citing contemporary U.S. counterinsurgency doctrine, notes that assertions of CIA involvement in the Ba'athist purge campaign "would be consistent with American special warfare doctrine" regarding U.S. covert support to anti-communist "Hunter-Killer" teams "seeking the violent overthrow of a communist dominated and supported government,"[191] and "speaks to a larger pattern in American foreign policy," drawing parallels to other instances where the CIA compiled lists of suspected communists targeted for execution, such as Guatemala in 1954 and Indonesia in 1965-66.[192] Also, Citino and Wolfe-Hunnicutt note that two officials in the U.S. embassy in Baghdad—William Lakeland and James E. Akins—"used coverage of the July 1962 Moscow Conference for Disarmament and Peace in Iraq's leftist press to compile lists of Iraqi communists and their supporters ... Those listed included merchants, students, members of professional societies, and journalists, although university professors constituted the largest single group."[193] Wolfe-Hunnicutt comments that "it’s not unreasonable to suspect [such a] list – or ones like it – would have been shared with the Ba‘ath."[194] Lakeland, a former SCI participant, "personally maintained contact following the coup with a National Guard interrogator," and may have been influenced by his prior interaction with then-Major Hasan Mustafa al-Naqib, the Iraqi military attaché in the U.S. who defected to the Ba'ath Party after Qasim "upheld Mahdawi's death sentences" against nationalists involved in the 1959 Mosul uprising. Furthermore, "Weldon C. Mathews has meticulously established that National Guard leaders who participated in human rights abuses had been trained in the United States as part of a police program run by the International Cooperation Administration and Agency for International Development."

The attacks on the people's freedoms carried out by the ... bloodthirsty members of the National Guard, their violation of things sacred, their disregard of the law, the injuries they have done to the state and the people, and finally their armed rebellion on November 13, 1963, has led to an intolerable situation which is fraught with grave dangers to the future of this people which is an integral part of the Arab nation. We have endured all we could. ... The army has answered the call of the people to rid them from this terror.

Legacy

[edit]

The 1958 Revolution can be considered a watershed in Iraqi politics, not just because of its obvious political implications (e.g. the abolition of monarchy, republicanism, and paving the way for Ba'athist rule) but also because of its domestic reforms. Despite its shortcomings, Qasim's rule helped to implement a number of positive domestic changes that benefited Iraqi society and were widely popular, especially the provision of low-cost housing to the inhabitants of Baghdad's urban slums. While criticising Qasim's "irrational and capricious behaviour" and "extraordinarily quixotic attempt to annex Kuwait in the summer of 1961", actions that raised "serious doubts about his sanity", Marion Farouk–Sluglett and Peter Sluglett conclude that, "Qasim's failings, serious as they were, can scarcely be discussed in the same terms as the venality, savagery and wanton brutality characteristic of the regimes which followed his own". Despite upholding death sentences against those involved in the 1959 Mosul uprising, Qasim also demonstrated "considerable magnanimity towards those who had sought at various times to overthrow him", including through large amnesties "in October and November 1961". Furthermore, not even Qasim's harshest critics could paint him as corrupt.[195]

Land reform

[edit]The revolution brought about sweeping changes in the Iraqi agrarian sector. Reformers dismantled the old feudal structure of rural Iraq. For example, the 1933 Law of Rights and Duties of Cultivators and the Tribal Disputes Code were replaced, benefiting Iraq's peasant population and ensuring a fairer process of law. The Agrarian Reform Law (30 September 1958[195]) attempted a large-scale redistribution of landholdings and placed ceilings on ground rents; the land was more evenly distributed among peasants who, due to the new rent laws, received around 55% to 70% of their crop.[195] While "inadequate" and allowing for "fairly generous" large holdings, the land reform was successful at reducing the political influence of powerful landowners, who under the Hashemite monarchy had wielded significant power.[195]

Women's rights

[edit]Qasim attempted to bring about greater equality for women in Iraq. In December 1959 he promulgated a significant revision of the personal status code, particularly that regulating family relations.[195] Polygamy was outlawed, and minimum ages for marriage were also set out, with 18 being the minimum age (except for special dispensation when it could be lowered by the court to 16).[195] Women were also protected from arbitrary divorce. The most revolutionary reform was a provision in Article 74 giving women equal rights in matters of inheritance.[195] The laws applied to Sunni and Shia alike. The laws encountered much opposition and did not survive Qasim's government.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Supported by the National Democratic Party and Iraqi Communist Party.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

- ^ Benjamin Shwadran, The Power Struggle in Iraq, Council for Middle Eastern Affairs Press, 1960

- ^ Dawisha (2009), p. 174

- ^ Yapp, Malcolm (2014). The Near East Since the First World War: A History to 1995. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-317-89054-6.

- ^ Bashkin, Orit (2009). The other Iraq: pluralism and culture in Hashemite Iraq. Stanford, California, USA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804774154.

- ^ a b By Kerim Yildiz, Georgina Fryer, Kurdish Human Rights Project. The Kurds: culture and language rights. Kurdish Human Rights Project, 2004. Pp. 58

- ^ "من ماهيات سيرة الزعيم عبد الكريم قاسم" (in Arabic). Am Mad as Supplements. 29 October 2014. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ "Modern Iraqi History and the Day After: Part 2, March 7, 2003". 16 May 2013. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ a b c Dann, Uriel (1969). Iraq under Qassem: A Political History, 1958–1963. London: Pall Mall Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0269670640.

- ^ "Iraqis Recall Golden Age". 2 September 2006. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "The Dissembler". Time. 13 April 1959.

- ^ Hunt 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Eppel 1998, p. 233.

- ^ Eppel 2004, p. 151.

- ^ a b Farouk-Sluglett, Marion; Sluglett, Peter (1991). "The Historiography of Modern Iraq". The American Historical Review. 96 (5): 1408–1421. doi:10.2307/2165278. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 2165278.

- ^ Feldman, Bob (2 February 2006). "A People's History of Iraq: 1950 to November 1963". Toward Freedom. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ Ufheil-Somers, Amanda (4 May 1992). "Why the Uprisings Failed". MERIP. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2014). Persian Gulf War Encyclopedia: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 355. ISBN 978-1-61069-415-5..

- ^ Al Hayah, Dar (1960). Majzarat Al Rihab: A Journalistic Investigation on the Death of the Hashemite Royal Family on 14 July 1958 in Baghdad (in Arabic). Beirut: Dar Al Hayah. p. 42.

- ^ a b c T. Abdullah, A Short History of Iraq: 636 to the present, Pearson Education, Harlow, UK (2003)

- ^ a b Marr (2004), p. 158

- ^ a b c d Mufti 2003, p. 173.

- ^ As in Kuwait for example: "The situation in Kuwait is very shaky as a result of the coup in Iraq, and there is a strong possibility that the revolutionary infection will spread there." See Keefer, Edward C.; LaFantasie, Glenn W., eds. (1993). "Special National Intelligence Estimate: The Middle East Crisis. Washington, July 22, 1958". Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Volume XII: Near East Region; Iraq; Iran; Arabian Peninsula. Washington, DC: Department of State. p. 90. The frantic Anglo-American reaction to the developments in Iraq, which Allen Dulles asserted was "primarily a UK responsibility", makes for an interesting read, beginning here.

- ^ Hailey, Foster (9 March 1959). "Iraqi Army Units Opposing Kassim Rebel in Oil Area". The New York Times. L3.

- ^ Simons 2003, p. 220

- ^ a b Marr 2003, p. 158.

- ^ a b Hunt 2005, p. 76.

- ^ Marr, Phebe; “The Modern History of Iraq”, page 164

- ^ Batatu, Hanna (2004). The Old Social Classes & The Revolutionary Movement In Iraq (PDF). Saqi Books. pp. 912–921. ISBN 978-0863565205. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Ahram, Ariel Ira (2011). Proxy Warriors: The Rise and Fall of State-Sponsored Militias. Stanford University Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9780804773591.

- ^ "IRAQ: The Revolt That Failed". Time. 23 March 1959. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Podeh, Elie (1999). The Decline of Arab Unity: The Rise and Fall of the United Arab Republic. Sussex Academic Press. p. 87. ISBN 1-902210-20-4.

- ^ Podeh, Elie (1999). The Decline of Arab Unity: The Rise and Fall of the United Arab Republic. Sussex Academic Press. p. 88. ISBN 1-902210-20-4.

- ^ Makiya, Kanan (1998). Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq, Updated Edition. University of California Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780520921245.

- ^ "60 years on, Iraqis reflect on the coup that killed King Faisal II". Arab News. 15 July 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Cleveland, William (2016). A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- ^ "ʿAbd al-Karīm Qāsim | Iraqi Prime Minister, Revolutionary Leader | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 3 April 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Faisal II | King, Iraq, & Death | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 26 April 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Reich, Bernard. Political leaders of the contemporary Middle East and North Africa: A Bibliographical Dictionary. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press, Ltd, 1990. Pp. 245.

- ^ Taylor, Katharine (May 2018). "Revolutionary Fervor: The History and Legacy of Communism in Abd al-Karim Qasim's Iraq 1958-1963". hdl:2152/65296.

- ^ katzcenterupenn. "What Do You Know? Iraq's Jewish History". Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Polk (2005), p. 111

- ^ Simons (1996), p. 221

- ^ Haifa, Prof Yehudit Henshke, University of (26 December 2021). "Abd al-Karim Qasim and treatment to Jews, The Preservation of Jewish Languages and Cultures in memory of Hayyim (Marani) Trabelsy". Mother Tongue. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tripp, Charles. A History of Iraq, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002, p.165

- ^ "Abdul Karim Qasim – A–Z Index – The Kurdistan Memory Programme". kurdistanmemoryprogramme.com. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Haddad, Fanar (2012). "Political Awakenings in an Artificial State: Iraq, 1914-20". academia.edu.

- ^ Westley, F.C. (1964). "A weekly review of politics, literature, theology, and art". The Spectator. 212: 473.

- ^ Bengio 1998, p. 218.

- ^ Seale 1990, p. 87.

- ^ Ali 2004, p. 105.

- ^ a b Batatu 1978, p. 701. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ "Iraq – Land Tenure and Agrarian Reform". countrystudies.us.

- ^ Al-Ali, Nadje (1 July 2012), Arenfeldt, Pernille; Golley, Nawar Al-Hassan (eds.), "The Iraqi Women's Movement: Past and Contemporary Perspectives", Mapping Arab Women's Movements, American University in Cairo Press, p. 107, doi:10.5743/cairo/9789774164989.003.0005, ISBN 978-977-416-498-9, retrieved 8 March 2020

- ^ "Dr. Naziha Jawdet Ashgah al-Dulaimi | Women as Partners in Progress Resource Hub". pioneersandleaders.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Iraq – Republican Iraq". countrystudies.us.

- ^ Marr (2004), p. 172

- ^ Rubin, Avshalom (13 April 2007). "Abd al-Karim Qasim and the Kurds of Iraq: Centralization, resistance and revolt, 1958–63". Middle Eastern Studies. 43 (3): 353–382. doi:10.1080/00263200701245944. S2CID 145177435.

- ^ The Washington Post (20 November 2017): "Women's rights are under threat in Iraq" By Zahra Ali.

- ^ Oron 1960, p. 271.

- ^ Ministry of Information 1971, p. 33.

- ^ Podeh 1999, p. 219. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPodeh1999 (help)

- ^ Coughlin 2005, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Coughlin 2005, p. 29.

- ^ Coughlin 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Seale 1990, p. 66.

- ^ Coughlin 2005, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Rabinovich 1972, p. 24.

- ^ "Background Note: Syria". United States Department of State, Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs. May 2007. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Marr (2004), p. 160

- ^ Kedourie, Elie; Politics in the Middle East, p. 318.

- ^ Rubin, Avshalom H. (2007). "Abd al-Karim Qasim and the Kurds of Iraq: Centralization, Resistance and Revolt, 1958-63". Middle Eastern Studies. 43 (3): 353–382. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4284550.

- ^ a b Ahram, Ariel Ira (2011). Proxy Warriors: The Rise and Fall of State-Sponsored Militias. Stanford University Press. pp. 75–77. ISBN 9780804773591.

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 396. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 399. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 393. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Salucci 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Ali Abel Sadah (24 April 2013). "Qasim's cooperation with Iraqi communists". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Salucci 2005, p. 24.

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 411. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 431. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Salucci 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 599. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Wien, Peter (2016). Arab Nationalism: The Politics of History and Culture in the Modern Middle East. London: Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-315-41219-1. OCLC 975005824.

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 603. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Salucci 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 438. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 693. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Tripp 2010, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 433. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Salucci 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Salucci 2005, p. 29.

- ^ Benjamin, Roger W.; Kautsky, John H.. Communism and Economic Development, in The American Political Science Review, Vol. 62, No. 1. (Mar. 1968), pp. 122.

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 442. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ Batatu 1978, p. 439. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBatatu1978 (help)

- ^ "Factualworld.com". www.factualworld.com.

- ^ David L. Phillips (2017). The Kurdish Spring: A New Map of the Middle East.

- ^ Gunter, Michael (2008). The Kurds Ascending. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-230-60370-7.

- ^ G.S. Harris, Ethnic Conflict and the Kurds, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, pp.118–120, 1977

- ^ Şahin, Tuncay. "What's the Algiers Agreement between Iran and Iraq about?". What's the Algiers Agreement between Iran and Iraq about?. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Saeed, Seevan (13 September 2016). Kurdish Politics in Turkey: From the PKK to the KCK. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 9781138195295.

- ^ By Kerim Yildiz, Georgina Fryer, Kurdish Human Rights Project. The Kurds: culture and language rights. Kurdish Human Rights Project, 2004. Pp. 58

- ^ Denise Natali. The Kurds and the state: evolving national identity in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. Syracuse, New York, USA: Syracuse University Press, 2005. Pp. 49.

- ^ Gunter, Michael (2008). The Kurds Ascending. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-230-60370-7.

- ^ a b Wadie Jwaideh. The Kurdish national movement: its origins and development. Syracuse, New York, USA: Syracuse University Press, 2006. Pp. 289.

- ^ Gunter, Michael; Denise Natali; Robert Olson; Nihat Ali Ozcan; Khaled Salih; M. Hakan Yavuz (March 2004). "The Kurds in Iraq". Middle East Policy. 11 (1): 106–131. doi:10.1111/j.1061-1924.2004.00145.x.

- ^ Roby Carol Barrett. "The greater Middle East and the Cold War: US foreign policy under Eisenhower and Kennedy", Library of international relations, Volume 30. I.B.Tauris, 2007. Pp. 90-91.

- ^ a b Masʻūd Bārzānī, Ahmed Ferhadi. Mustafa Barzani and the Kurdish liberation movement (1931–1961). New York, New York, USA; Hampshire, England, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Pp. 180-181.

- ^ a b Ghareeb, Edmund; Ghareeb, Adjunct Professor of History Edmund (1981). The Kurdish Question in Iraq (1st ed.). Syracuse University Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-8156-0164-6. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ a b Marr (2004), p. 178

- ^ Korn, David (1994-06). "The Last Years of Mustafa Barzani." Archived 22 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine Middle East Quarterly. Archived 8 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ Bartu, Peter (2010). "Wrestling With the Integrity of A Nation: The Disputed Internal Boundaries in Iraq". International Affairs. 6. 86 (6): 1329–1343. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2010.00946.x.

- ^ Yitzhak Oron, Ed. Middle East Record Volume 2, 1961. Pp. 281.

- ^ Wadie Jwaideh. The Kurdish national movement: its origins and development. Syracuse, New York, USA: Syracuse University Press, 2006. Pp. 289.

- ^ Helen Chapin Metz, ed., Iraq A Country Study. Kessinger Publishing, 2004 Pp. 65.

- ^ Raymond A. Hinnebusch. The international politics of the Middle East. Manchester, England, UK: Manchester University Press, 2003 Pp. 209.

- ^ Smolansky, Oles M. (1967). "Qasim and the Iraqi Communist Party; A Study in Arab Politics". Il Politico. 32 (2): 292–307. ISSN 0032-325X. JSTOR 43209470.

- ^ Marr (2004), p. 163

- ^ Coughlin (2005), pp. 24–25

- ^ Coughlin (2005), pp. 25–26

- ^ Coughlin (2005), p. 26

- ^ Coughlin (2005), p. 27

- ^ Coughlin (2005), p. 30

- ^ a b c Marr (2004), p. 164

- ^ a b cf. Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (March 2011). "The End of the Concessionary Regime: Oil and American Power in Iraq, 195–1972". p. 55, footnote 70. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Goktepe, Cihat (October 1999). "The 'Forgotten Alliance'? Anglo-Turkish Relations and CENTO, 1959-65". Middle Eastern Studies. 35 (4). London: 103. doi:10.1080/00263209908701288. ISSN 0026-3206. OCLC 1049994615.

- ^ Casey, William Francis, ed. (7 April 1959). "R.A.F. Families Leave Habbaniya". The Times. No. 54428. p. 10. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ Casey, William Francis, ed. (6 April 1959). "Habbaniya Families Leave To-Day". The Times. No. 54427. p. 10. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ^ "Habbaniya". hansard.parliament.uk. 15 July 1959. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Marr (2004), p. 180

- ^ Farhang Rajaee, The Iran-Iraq War (University Press of Florida, 1993), pp. 111–112.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim, The Iran-Iraq War: 1980–1988, London: Osprey, 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim (25 April 2002). The Iran–Iraq War: 1980–1988. Osprey Publishing. pp. 1–8, 12–16, 19–82. ISBN 978-1-84176-371-2.

- ^ Farrokh, Kaveh (20 December 2011). Iran at War: 1500–1988. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-221-4.

- ^ "The Origin and Development of Imperialist Contention in Iran; 1884–1921". History of Iran. Iran Chamber Society. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Marr (2004), p. 181

- ^ Simons (1996), pp. 223–225

- ^ Brogan, Patrick (1989). World Conflicts: A Comprehensive Guide to World Strife Since 1945. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-0260-9.

- ^ Ranard, Donald A. (ed.). "History". Iraqis and Their Culture. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2017). "Oil Sovereignty, American Foreign Policy, and the 1968 Coups in Iraq". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 28 (2). Routledge: 235–253. doi:10.1080/09592296.2017.1309882. S2CID 157328042.

- ^ Gibson (2015), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Little, Douglas. American Orientalism: The United States and the Middle East Since 1945. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 62.

- ^ Styan, David. France and Iraq: Oil, Arms and French Policy Making in the Middle East. I.B. Tauris, 2006. p. 74.

- ^ Polk (2005), p. 111

- ^ Simons (1996), p. 221

- ^ "Factualworld.com". www.factualworld.com.

- ^ Marr (2004), p. 181

- ^ Simons (1996), pp. 223–225

- ^ "Desert Storm: 30 years on". Arab News. 27 February 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "Iraq - REPUBLICAN IRAQ". countrystudies.us.

- ^ Marr (2004), p. 172

- ^ The Washington Post (November 20, 2017): "Women's rights are under threat in Iraq" By Zahra Ali.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2021). The Paranoid Style in American Diplomacy: Oil and Arab Nationalism in Iraq. Stanford University Press. pp. 86–87, 93–102. ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

- ^ Gibson (2015), pp. 35–45.

- ^ Matthews, Weldon C. (9 November 2011). "The Kennedy Administration, Counterinsurgency, and Iraq's First Ba'thist Regime". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 43 (4): 635–653. doi:10.1017/S0020743811000882. ISSN 0020-7438. S2CID 159490612.

[Kennedy] Administration officials viewed the Iraqi Ba'th Party in 1963 as an agent of counterinsurgency directed against Iraqi communists, and they cultivated supportive relationships with Ba'thist officials, police commanders, and members of the Ba'th Party militia. The American relationship with militia members and senior police commanders had begun even before the February coup, and Ba'thist police commanders involved in the coup had been trained in the United States.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, B. (1 January 2015). "Embracing Regime Change in Iraq: American Foreign Policy and the 1963 Coup d'etat in Baghdad". Diplomatic History. 39 (1): 98–125. doi:10.1093/dh/dht121. ISSN 0145-2096.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, B. (1 January 2015). "Embracing Regime Change in Iraq: American Foreign Policy and the 1963 Coup d'etat in Baghdad". Diplomatic History. 39 (1): 98–125. doi:10.1093/dh/dht121. ISSN 0145-2096.

While scholars and journalists have long suspected that the CIA was involved in the 1963 coup, as yet, there is very little archival analysis of the question. The most comprehensive study put forward thus far finds "mounting evidence of U.S. involvement" but ultimately runs up against the problem of available documentation.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2021). The Paranoid Style in American Diplomacy: Oil and Arab Nationalism in Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

What really happened in Iraq in February 1963 remains shrouded behind a veil of official secrecy. Many of the most relevant documents remain classified. Others were destroyed. And still others were never created in the first place.

- ^ Matthews, Weldon C. (9 November 2011). "The Kennedy Administration, Counterinsurgency, and Iraq's First Ba'thist Regime". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 43 (4): 635–653. doi:10.1017/S0020743811000882. ISSN 1471-6380. S2CID 159490612.

Archival sources on the U.S. relationship with this regime are highly restricted. Many records of the Central Intelligence Agency's operations and the Department of Defense from this period remain classified, and some declassified records have not been transferred to the National Archives or cataloged.

- ^ Osgood, Kenneth (2009). "Eisenhower and regime change in Iraq: the United States and the Iraqi Revolution of 1958". America and Iraq: Policy-making, Intervention and Regional Politics. Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 9781134036721.

The documentary record is filled with holes. A remarkable volume of material remains classified, and those records that are available are obscured by redactions – large blacked-out sections that allow for plausible deniability. While it is difficult to know exactly what actions were taken to destabilize or overthrow Qasim's regime, we can discern fairly clearly what was on the planning table. We also can see clues as to what was authorized.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2021). The Paranoid Style in American Diplomacy: Oil and Arab Nationalism in Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

- ^ For additional sources that agree or sympathize with assertions of U.S. involvement, see:

- Ismael, Tareq Y.; Ismael, Jacqueline S.; Perry, Glenn E. (2016). Government and Politics of the Contemporary Middle East: Continuity and Change (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-317-66282-2.

Ba'thist forces and army officers overthrew Qasim on February 8, 1963, in collaboration with the CIA.

- Little, Douglas (14 October 2004). "Mission Impossible: The CIA and the Cult of Covert Action in the Middle East". Diplomatic History. 28 (5): 663–701. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2004.00446.x. ISSN 1467-7709.

Such self-serving denials notwithstanding, the CIA actually appears to have had a great deal to do with the bloody Ba'athist coup that toppled Qassim in February 1963. Deeply troubled by Qassim's steady drift to the left, by his threats to invade Kuwait, and by his attempt to cancel Western oil concessions, U.S. intelligence made contact with anticommunist Ba'ath activists both inside and outside the Iraqi army during the early 1960s.

- Osgood 2009, pp. 26–27, "Working with Nasser, the Ba'ath Party, and other opposition elements, including some in the Iraqi army, the CIA by 1963 was well positioned to help assemble the coalition that overthrew Qasim in February of that year. It is not clear whether Qasim's assassination, as Said Aburish has written, was 'one of the most elaborate CIA operations in the history of the Middle East.' That judgment remains to be proven. But the trail linking the CIA is suggestive."

- Mitchel, Timothy (2002). Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. University of California Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780520928251.

Qasim was killed three years later in a coup welcomed and possibly aided by the CIA, which brought to power the Ba'ath, the party of Saddam Hussein.

- Sluglett, Peter (2004). "The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq's Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of its Communists, Ba'thists and Free Officers (Review)" (PDF). Democratiya. p. 9.

Batatu infers on pp. 985-86 that the CIA was involved in the coup of 1963 (which brought the Ba'ath briefly to power): Even if the evidence here is somewhat circumstantial, there can be no question about the Ba'ath's fervent anti-communism.

- Weiner, Tim (2008). Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. Doubleday. p. 163. ISBN 9780307455628.

The agency finally backed a successful coup in Iraq in the name of American influence.

- Ismael, Tareq Y.; Ismael, Jacqueline S.; Perry, Glenn E. (2016). Government and Politics of the Contemporary Middle East: Continuity and Change (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-317-66282-2.

- ^ For additional sources that dispute assertions of U.S. involvement, see:

- Barrett, Roby C. (2007). The Greater Middle East and the Cold War: US Foreign Policy Under Eisenhower and Kennedy. I.B. Tauris. p. 451. ISBN 9780857713087.

Washington wanted to see Qasim and his Communist supporters removed, but that is a far cry from Batatu's inference that the U.S. had somehow engineered the coup. The U.S. lacked the operational capability to organize and carry out the coup, but certainly after it had occurred the U.S. government preferred the Nasserists and Ba'athists in power, and provided encouragement and probably some peripheral assistance.

- West, Nigel (2017). Encyclopedia of Political Assassinations. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 205. ISBN 9781538102398.

Although Qasim was regarded as an adversary by the West, having nationalized the Iraq Petroleum Company, which had joint Anglo-American ownership, no plans had been made to depose him, principally because of the absence of a plausible successor. Nevertheless, the CIA pursued other schemes to prevent Iraq from coming under Soviet influence, and one such target was an unidentified colonel, thought to have been Qasim's cousin, the notorious Fadhil Abbas al-Mahdawi who was appointed military prosecutor to try members of the previous Hashemite monarchy.

- Barrett, Roby C. (2007). The Greater Middle East and the Cold War: US Foreign Policy Under Eisenhower and Kennedy. I.B. Tauris. p. 451. ISBN 9780857713087.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. xvii, 58, 200.

- ^ Hahn, Peter (2011). Missions Accomplished?: The United States and Iraq Since World War I. Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780195333381.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2021). The Paranoid Style in American Diplomacy: Oil and Arab Nationalism in Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

- ^ Jacobsen, E. (1 November 2013). "A Coincidence of Interests: Kennedy, U.S. Assistance, and the 1963 Iraqi Ba'th Regime". Diplomatic History. 37 (5): 1029–1059. doi:10.1093/dh/dht049. ISSN 0145-2096.

- ^ Citino, Nathan J. (2017). "The People's Court". Envisioning the Arab Future: Modernization in US-Arab Relations, 1945–1967. Cambridge University Press. pp. 182–183, 218–219. ISBN 978-1108107556.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2021). The Paranoid Style in American Diplomacy: Oil and Arab Nationalism in Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

- ^ a b c Wolfe-Hunnicutt, B. (1 January 2015). "Embracing Regime Change in Iraq: American Foreign Policy and the 1963 Coup d'etat in Baghdad". Diplomatic History. 39 (1): 98–125. doi:10.1093/dh/dht121. ISSN 0145-2096.

- ^ Matthews, Weldon C. (11 November 2011). "The Kennedy Administration, Counterinsurgency, and Iraq's First Ba'thist Regime". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 43 (4): 635–653. doi:10.1017/S0020743811000882. ISSN 1471-6380. S2CID 159490612.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (2021). The Paranoid Style in American Diplomacy: Oil and Arab Nationalism in Iraq. Stanford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-5036-1382-9.

- ^ Mufti, Malik (1996). Sovereign Creations: Pan-Arabism and Political Order in Syria and Iraq. Cornell University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780801431685.

- ^ a b Jacobsen, E. (1 November 2013). "A Coincidence of Interests: Kennedy, U.S. Assistance, and the 1963 Iraqi Ba'th Regime". Diplomatic History. 37 (5): 1029–1059. doi:10.1093/dh/dht049. ISSN 0145-2096.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, Brandon (March 2011). "The End of the Concessionary Regime: Oil and American Power in Iraq, 1958-1972" (PDF). p. 87.

- ^ Little, Allan (26 January 2003). "Saddam's parallel universe". BBC News.

- ^ Makiya, Kanan (1998). Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq, Updated Edition. University of California Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0520921245.

- ^ Citino, Nathan J. (2017). "The People's Court". Envisioning the Arab Future: Modernization in US-Arab Relations, 1945–1967. Cambridge University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-1108107556.

- ^ a b Makiya, Kanan (1998). Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq, Updated Edition. University of California Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0520921245.

- ^ Coughlin (2005), p. 41.

- ^ Gibson 2015, pp. 60–61, 72, 80.

- ^ Wolfe-Hunnicutt, B. (1 January 2015). "Embracing Regime Change in Iraq: American Foreign Policy and the 1963 Coup d'etat in Baghdad". Diplomatic History. 39 (1): 98–125. doi:10.1093/dh/dht121. ISSN 0145-2096.

- ^ "Iraq: Green Armbands, Red Blood". Time. 22 February 1963. ISSN 0040-781X.

- ^ Batatu, Hanna (1978). The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq's Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of its Communists, Ba'thists and Free Officers. Princeton University Press. pp. 985–987. ISBN 978-0863565205.