World Chess Championship

| List of World Chess Championships |

|---|

The World Chess Championship is played to determine the world champion in chess. The current world champion is Ding Liren, who defeated Ian Nepomniachtchi in the 2023 World Chess Championship after the previous champion Magnus Carlsen had declined to defend his title. Liren is presently defending his title against Gukesh Dommaraju in the 2024 World Chess Championship tournament.

The first event recognized as a world championship was the 1886 match between Wilhelm Steinitz and Johannes Zukertort, which was won by Steinitz, who became the first world champion. From 1886 to 1946, the champion set the terms, requiring any challenger to raise a sizable stake and defeat the champion in a match in order to become the new world champion. Following the death of reigning world champion Alexander Alekhine in 1946, the International Chess Federation (FIDE) took over administration of the World Championship, beginning with the 1948 tournament. From 1948 to 1993, FIDE organized a set of tournaments and matches to choose a new challenger for the world championship match, which was held every three years.

Before the 1993 match, then reigning champion Garry Kasparov and his championship rival Nigel Short broke away from FIDE, and conducted the match under the umbrella of the newly formed Professional Chess Association. FIDE conducted its own tournament, which was won by Anatoly Karpov, and led to a rival claimant to the title of World Champion for the next thirteen years until 2006. The titles were unified at the World Chess Championship 2006, and all the subsequent tournaments and matches have once again been administered by FIDE. Since 2014, the championship has settled on a two-year cycle, with championship matches conducted every even year. The 2020 and 2022 tournaments were postponed to 2021 and 2023 respectively because of the COVID-19 pandemic.[1] The next tournament returned to the normal schedule and was held in 2024.

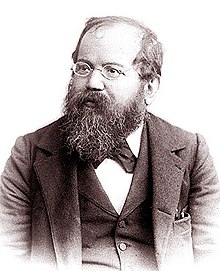

Emanuel Lasker was the longest serving World Champion, having held the title for 27 years, and holds the record for the most Championship wins with six along with Kasparov and Karpov. Though the world championship is open to all players, there are separate championships for women, under-20s and lower age groups, and seniors. There are also chess world championships in rapid, blitz, correspondence, problem solving, Fischer random chess, and computer chess.

History

[edit]Early champions (pre-1886)

[edit]Before 1851

[edit]

The game of chess in its modern form emerged in Spain in the 15th century, though rule variations persisted until the late 19th century. Before Wilhelm Steinitz and Johannes Zukertort in the late 19th century, no chess player seriously claimed to be champion of the world. The phrase was used by some chess writers to describe other players of their day, and the status of being the best at the time has sometimes been awarded in retrospect, going back to the early 17th-century Italian player Gioachino Greco (the first player where complete games survive).[2] Richard Lambe, in his 1764 book The History of Chess, wrote that the 18th-century French player François-André Danican Philidor was "supposed to be the best Chess-player in the world".[3] Philidor wrote an extremely successful chess book (Analyse du jeu des Échecs) and gave public demonstrations of his blindfold chess skills.[4] However, some of Philidor's contemporaries were not convinced by the analysis Philidor gave in his book (e.g. the Modenese Masters), and some more recent authors have echoed these doubts.[5][6][2]

In the early 19th century, it was generally considered that the French player Alexandre Deschapelles was the strongest player of the time, though three games between him and the English player William Lewis in 1821 suggests that they were on par.[7] After Deschapelles and Lewis withdrew from play, the strongest players from France and England respectively were recognised as Louis de la Bourdonnais and Alexander McDonnell. La Bourdonnais visited England in 1825, where he played many games against Lewis and won most of them, and defeated all the other English masters despite offering handicaps.[8] He and McDonnell contested a long series of matches in 1834. These were the first to be adequately reported,[9] and they somewhat resemble the later world championship matches. Approximately 85 games (the true number is up for historical debate) were played,[10] with La Bourdonnais winning a majority of the games.[11]

In 1839, George Walker wrote "The sceptre of chess, in Europe, has been for the last century, at least, wielded by a Gallic dynasty. It has passed from Legalle [Philidor's teacher, who Philidor regarded as being a player equal to himself, according to Deschapelles][13] to La Bourdonnais, through the grasp, successively, of Philidor, Bernard, Carlier [two members of La Société des Amateurs], and Deschapelles".[14] In 1840, a columnist in Fraser's Magazine (who was probably Walker) wrote, "Will Gaul continue the dynasty by placing a fourth Frenchman on the throne of the world? the three last chess chiefs having been successively Philidor, Deschapelles, and De La Bourdonnais."[15][16]

After La Bourdonnais' death in December 1840,[17] Englishman Howard Staunton's match victory over another Frenchman, Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant, in 1843 is considered to have established Staunton as the world's strongest player,[18][15] at least in England and France. By the 1830s, players from Germany and more generally Central Europe were beginning to appear on the scene:[9] the strongest of the Berlin players around 1840 was probably Ludwig Bledow, co-founder of the Berlin Pleiades.[19] The earliest recorded use of the term "World Champion" was in 1845, when Staunton was described as "the Chess Champion of England, or ... the Champion of the World".[20]

From 1851 to 1886

[edit]An important milestone was the London 1851 chess tournament, which was the first international chess tournament, organized by Staunton. It was played as a series of matches, and was won convincingly by the German Adolf Anderssen, including a 4–1 semi-final win over Staunton. This established Anderssen as the world's leading player.[22] In 1893, Henry Bird retrospectively awarded the title of first world chess champion to Anderssen for his victory,[24] but there is no evidence that he was widely acclaimed as such at the time, and no mention of such a status afterwards in the tournament book by Staunton. Indeed, Staunton's tournament book calls Anderssen "after Heydebrand der Laza [Tassilo von der Lasa, another of the Berlin Pleiades], the best player of Germany": von der Lasa was unable to attend the 1851 tournament, though he was invited.[25] In 1851, Anderssen lost a match to von der Lasa;[26] in 1856, George Walker wrote that "[von der Lasa] and Anderssen are decidedly the two best in the known world".[27] Von der Lasa did not compete in tournaments or formal matches because of the demands of his diplomatic career, but his games show that he was one of the world's best then: he won series of games against Staunton in 1844 and 1853.[26]

Anderssen was himself decisively beaten in an 1858 match against the American Paul Morphy (7–2, 2 draws). In 1858–59 Morphy played matches against several leading players, beating them all.[28][29] This prompted some commentators at the time to call him the world champion:[30] Gabriel-Éloy Doazan, who knew Morphy, wrote that "one can and...must place [him] in the same bracket" as Deschapelles and La Bourdonnais, who he had played years before, and that "his superiority is as obvious as theirs".[31] But when Morphy returned to America in 1859, he abruptly retired from chess, though many considered him the world champion until his death in 1884. His sudden withdrawal from chess at his peak led to his being known as "the pride and sorrow of chess".[32]

After Morphy's retirement from chess, Anderssen was again regarded as the world's strongest active player,[33] a reputation he reinforced by winning the strong London 1862 chess tournament.[33] Louis Paulsen and Ignatz Kolisch were also playing at a comparable standard to Anderssen in the 1860s:[33][34] Anderssen narrowly won a match against Kolisch in 1861, and drew against Paulsen in 1862.[33]

In 1866, Wilhelm Steinitz narrowly defeated Anderssen in a match (8–6, 0 draws). However, he was not immediately able to conclusively demonstrate his superiority. Steinitz placed third at the Paris 1867 chess tournament, behind Kolisch and Szymon Winawer; he placed second at the Dundee 1867 tournament, behind Gustav Neumann;[35] and he again placed second at the Baden-Baden 1870 chess tournament, which was the strongest that had been held to date (Anderssen came first, and won twice against Steinitz).[21][36] Steinitz confirmed his standing as the world's leading player by winning the London 1872 tournament, winning a match against Johannes Zukertort in 1872 (7–1, 4 draws), winning the Vienna 1873 chess tournament, and decisively winning a match over Joseph Henry Blackburne 7–0 (0 draws) in 1876.[37]

Apart from the Blackburne match, Steinitz played no competitive chess between the Vienna tournaments of 1873 and 1882. During that time, Zukertort emerged as the world's leading active player, winning the Paris 1878 chess tournament. Zukertort then won the London 1883 chess tournament by a convincing 3-point margin, ahead of nearly every leading player in the world, with Steinitz finishing second.[38][39] This tournament established Steinitz and Zukertort as the best two players in the world, and led to a match between these two, the World Chess Championship 1886,[39][40] won by Steinitz.

There is some debate over whether to date Steinitz's reign as world champion from his win over Anderssen in 1866, or from his win over Zukertort in 1886. The 1886 match was clearly agreed to be for the world championship,[41][30] but there is no indication that Steinitz was regarded as the defending champion.[42] There is also no known evidence of Steinitz being called the world champion after defeating Anderssen in 1866.[30] It has been suggested that Steinitz could not make such a claim while Morphy was alive[43] (Morphy died in 1884). There are a number of references to Steinitz as world champion in the 1870s, the earliest being after the first Zukertort match in 1872.[30] Later, in 1879, it was argued that Zukertort was world champion, since Morphy and Steinitz were not active.[30] However, later in his career, at least from 1887, Steinitz dated his reign from this 1866 match,[30] and early sources such as the New York Times in 1894,[44] Emanuel Lasker in 1908,[30] and Reuben Fine in 1952[45] all do the same.

Many modern commentators divide Steinitz's reign into an "unofficial" one from 1866 to 1886, and an "official" one after 1886.[46][47][48] By this reckoning, the first World Championship match was in 1886, and Steinitz was the first official World Chess Champion.[49]

Champions before FIDE (1886–1946)

[edit]Reign of Wilhelm Steinitz (1886–1894)

[edit]

Following the Steinitz–Zukertort match, a tradition continued of the world championship being decided by a match between the reigning champion, and a challenger: if a player thought he was strong enough, he (or his friends) would find financial backing for a match purse and challenge the reigning world champion. If he won, he would become the new champion.

Steinitz successfully defended his world title against Mikhail Chigorin in 1889, Isidor Gunsberg in 1891, and Chigorin again in 1892.

In 1887, the American Chess Congress started work on drawing up regulations for the future conduct of world championship contests. Steinitz supported this endeavor, as he thought he was becoming too old to remain world champion. The proposal evolved through many forms (as Steinitz pointed out, such a project had never been undertaken before), and resulted in the 1889 tournament in New York to select a challenger for Steinitz[citation needed], rather like the more recent Candidates Tournaments. The tournament was duly played, but the outcome was not quite as planned: Chigorin and Max Weiss tied for first place; their play-off resulted in four draws; and neither wanted to play a match against Steinitz – Chigorin had just lost to him, and Weiss wanted to get back to his work for the Rothschild Bank. The third prizewinner, Isidor Gunsberg, was prepared to play Steinitz for the title in New York, so this match was played in 1890–1891 and was won by Steinitz.[50][51][52] The experiment was not repeated, and Steinitz's later matches were private arrangements between the players.[44]

Two young strong players emerged in late 1880s and early 1890s: Siegbert Tarrasch and Emanuel Lasker.[53] Tarrasch had the better tournament results at the time, but it was Lasker who was able to raise the money to challenge Steinitz.[53] Lasker won the 1894 match and succeeded Steinitz as world champion.

Emanuel Lasker (1894–1921)

[edit]

Lasker held the title from 1894 to 1921, the longest reign (27 years) of any champion. He won a return match against Steinitz in 1897, and then did not defend his title for ten years, before playing four title defences in four years. He comfortably defeated Frank Marshall in 1907 and Siegbert Tarrasch in 1908. In 1910, he almost lost his title in a short tied match against Carl Schlechter, although the exact conditions of this match are a mystery. He then defeated Dawid Janowski in the most one-sided title match in history later in 1910.

Lasker's negotiations for title matches from 1911 onwards were extremely controversial. In 1911, he received a challenge for a world title match against José Raúl Capablanca and, in addition to making severe financial demands, proposed some novel conditions: the match should be considered drawn if neither player finished with a two-game lead; and it should have a maximum of 30 games, but finish if either player won six games and had a two-game lead (previous matches had been won by the first to win a certain number of games, usually 10; in theory, such a match might go on for ever). Capablanca objected to the two-game lead clause; Lasker took offence at the terms in which Capablanca criticized the two-game lead condition and broke off negotiations.[54]

Further controversy arose when, in 1912, Lasker's terms for a proposed match with Akiba Rubinstein included a clause that, if Lasker should resign the title after a date had been set for the match, Rubinstein should become world champion.[55] When he resumed negotiations with Capablanca after World War I, Lasker insisted on a similar clause that if Lasker should resign the title after a date had been set for the match, Capablanca should become world champion.[54] On 27 June 1920 Lasker abdicated in favor of Capablanca because of public criticism of the terms of the match, naming Capablanca as his successor.[55] Some commentators questioned Lasker's right to name his successor;[55] Amos Burn raised the same objection but welcomed Lasker's resignation of the title.[55] Capablanca argued that, if the champion abdicated, the title must go to the challenger, as any other arrangement would be unfair to the challenger.[55] Lasker later agreed to play a match against Capablanca in 1921, announcing that, if he won, he would resign the title so that younger masters could compete for it.[55] Capablanca won their 1921 match by four wins, ten draws and no losses.[45]

Capablanca, Alekhine and Euwe (1921–1946)

[edit]After the breakdown of his first attempt to negotiate a title match against Lasker (1911), Capablanca drafted rules for the conduct of future challenges, which were agreed to by the other top players at the 1914 Saint Petersburg tournament, including Lasker, and approved at the Mannheim Congress later that year. The main points were: the champion must be prepared to defend his title once a year; the match should be won by the first player to win six or eight games (the champion had the right to choose); and the stake should be at least £1,000 (about £120,000 in current terms).[54]

Following the controversies surrounding his 1921 match against Lasker, in 1922 world champion Capablanca proposed the "London Rules": the first player to win six games would win the match; playing sessions would be limited to 5 hours; the time limit would be 40 moves in 2½ hours; the champion must defend his title within one year of receiving a challenge from a recognized master; the champion would decide the date of the match; the champion was not obliged to accept a challenge for a purse of less than US$10,000 (about $170,000 in current terms); 20% of the purse was to be paid to the title holder, and the remainder being divided, 60% going to the winner of the match, and 40% to the loser; the highest purse bid must be accepted. Alekhine, Bogoljubow, Maróczy, Réti, Rubinstein, Tartakower and Vidmar promptly signed them.[56] The only match played under those rules was Capablanca vs Alekhine in 1927, although there has been speculation that the actual contract might have included a "two-game lead" clause.[57]

Alekhine, Rubinstein and Nimzowitsch had all challenged Capablanca in the early 1920s but only Alekhine could raise the US$10,000 Capablanca demanded and only in 1927.[58] Capablanca was shockingly upset by the new challenger. Before the match, almost nobody gave Alekhine a chance against the dominant Cuban, but Alekhine overcame Capablanca's natural skill with his unmatched drive and extensive preparation (especially deep opening analysis, which became a hallmark of most future grandmasters). The aggressive Alekhine was helped by his tactical skill, which complicated the game. Immediately after winning, Alekhine announced that he was willing to grant Capablanca a return match provided Capablanca met the requirements of the "London Rules".[57] Negotiations dragged on for several years, often breaking down when agreement seemed in sight.[45] Alekhine easily won two title matches against Efim Bogoljubov in 1929 and 1934. In 1935, Alekhine was unexpectedly defeated by the Dutch Max Euwe, an amateur player who worked as a mathematics teacher. Alekhine convincingly won a rematch in 1937. World War II temporarily prevented any further world title matches, and Alekhine remained world champion until his death in 1946.

Financing

[edit]Before 1948 world championship matches were financed by arrangements similar to those Emanuel Lasker described for his 1894 match with Wilhelm Steinitz: either the challenger or both players, with the assistance of financial backers, would contribute to a purse; about half would be distributed to the winner's backers, and the winner would receive the larger share of the remainder (the loser's backers got nothing). The players had to meet their own travel, accommodation, food and other expenses out of their shares of the purse.[59] This system evolved out of the wagering of small stakes on club games in the early 19th century.[60]

Up to and including the 1894 Steinitz–Lasker match, both players, with their backers, generally contributed equally to the purse, following the custom of important matches in the 19th century before there was a generally recognized world champion. For example: the stakes were £100 a side in both the second Staunton vs Saint-Amant match (Paris, 1843) and the Anderssen vs Steinitz match (London, 1866); Steinitz and Zukertort played their 1886 match for £400 a side.[60] Lasker introduced the practice of demanding that the challenger should provide the whole of the purse,[citation needed] and his successors followed his example up to World War II. This requirement made arranging world championship matches more difficult, for example: Marshall challenged Lasker in 1904 but could not raise the money until 1907;[61] in 1911 Lasker and Rubinstein agreed in principle to a world championship match, but this was never played as Rubinstein could not raise the money.[62][63] In the early 1920s, Alekhine, Rubinstein and Nimzowitsch all challenged Capablanca, but only Alekhine was able to raise the US$10,000 that Capablanca demanded, and not until 1927.[58][64]

FIDE title (1948–1993)

[edit]FIDE, Euwe and AVRO

[edit]

Attempts to form an international chess federation were made at the time of the 1914 St. Petersburg, 1914 Mannheim and 1920 Gothenburg Tournaments.[65] On 20 July 1924 the participants at the Paris tournament founded FIDE as a kind of players' union.[65][66][67] FIDE's congresses in 1925 and 1926 expressed a desire to become involved in managing the world championship. FIDE was largely happy with the "London Rules", but claimed that the requirement for a purse of $10,000 was impracticable and called upon Capablanca to come to an agreement with the leading masters to revise the Rules. In 1926 FIDE decided in principle to create a title of "Champion of FIDE" and, in 1928, adopted the forthcoming 1928 Bogoljubow–Euwe match (won by Bogoljubow) as being for the "FIDE championship". Alekhine agreed to place future matches for the world title under the auspices of FIDE, except that he would only play Capablanca under the same conditions that governed their match in 1927. Although FIDE wished to set up a match between Alekhine and Bogoljubow, it made little progress and the title "Champion of FIDE" quietly vanished after Alekhine won the 1929 world championship match that he and Bogoljubow themselves arranged.[68]

While negotiating his 1937 World Championship rematch with Alekhine, Euwe proposed that if he retained the title, FIDE should manage the nomination of future challengers and the conduct of championship matches. FIDE had been trying since 1935 to introduce rules on how to select challengers, and its various proposals favored selection by some sort of committee. While they were debating procedures in 1937 and Alekhine and Euwe were preparing for their rematch later that year, the Royal Dutch Chess Federation proposed that a super-tournament (AVRO) of ex-champions and rising stars should be held to select the next challenger. FIDE rejected this proposal and at their second attempt nominated Salo Flohr as the official challenger. Euwe then declared that: if he retained his title against Alekhine he was prepared to meet Flohr in 1940 but he reserved the right to arrange a title match either in 1938 or 1939 with José Raúl Capablanca, who had lost the title to Alekhine in 1927; if Euwe lost his title to Capablanca then FIDE's decision should be followed and Capablanca would have to play Flohr in 1940. Most chess writers and players strongly supported the Dutch super-tournament proposal and opposed the committee processes favored by FIDE. While this confusion went unresolved: Euwe lost his title to Alekhine; the AVRO tournament in 1938 was won by Paul Keres under a tie-breaking rule, with Reuben Fine placed second and Capablanca and Flohr in the bottom places; and the outbreak of World War II in 1939 cut short the controversy.[69]

Birth of FIDE's World Championship cycle (1946–1948)

[edit]Alexander Alekhine died in 1946 before anyone else could win against him in match for the World Champion title. This resulted in an interregnum that made the normal procedure impossible. The situation was very confused, with many respected players and commentators offering different solutions. FIDE found it very difficult to organize the early discussions on how to resolve the interregnum because problems with money and travel so soon after the end of World War II prevented many countries from sending representatives. The shortage of clear information resulted in otherwise responsible magazines publishing rumors and speculation, which only made the situation more confusing.[70] It did not help that the Soviet Union had long refused to join FIDE, and by this time it was clear that about half the credible contenders were Soviet citizens. But, realizing that it could not afford to be excluded from discussions about the vacant world championship, the Soviet Union sent a telegram in 1947 apologizing for the absence of Soviet representatives and requesting that the USSR be represented on future FIDE Committees.[70]

The eventual solution was very similar to FIDE's initial proposal and to a proposal put forward by the Soviet Union (authored by Mikhail Botvinnik). The 1938 AVRO tournament was used as the basis for the 1948 Championship Tournament. The AVRO tournament had brought together the eight players who were, by general acclamation, the best players in the world at the time. Two of the participants at AVRO – Alekhine and former world champion José Raúl Capablanca – had died; but FIDE decided that the championship should be awarded to the winner of a round-robin tournament in which the other six participants at AVRO would play four games against each other. These players were: Max Euwe, from the Netherlands; Botvinnik, Paul Keres and Salo Flohr from the Soviet Union; and Reuben Fine and Samuel Reshevsky from the United States. However, FIDE soon accepted a Soviet request to substitute Vasily Smyslov for Flohr, and Fine dropped out in order to continue his degree studies in psychology, so only five players competed. Botvinnik won convincingly and thus became world champion, ending the interregnum.[70]

The proposals which led to the 1948 Championship Tournament also specified the procedure by which challengers for the World Championship would be selected in a three-year cycle: countries affiliated to FIDE would send players to Zonal Tournaments (the number varied depending on how many good enough players each country had); the players who gained the top places in these would compete in an Interzonal Tournament (later split into two and then three tournaments as the number of countries and eligible players increased[71]); the highest-placed players from the Interzonal would compete in the Candidates Tournament, along with whoever lost the previous title match and the second-placed competitor in the previous Candidates Tournament three years earlier; and the winner of the Candidates played a title match against the champion.[70] Until 1962 inclusive the Candidates Tournament was a multi-cycle round-robin tournament – how and why it was changed are described below.

FIDE system (1949–1963)

[edit]The FIDE system followed its 1948 design through five cycles: 1948–1951, 1951–1954, 1954–1957, 1957–1960 and 1960–1963.[72][73] The first two world championships under this system were drawn 12–12 – Botvinnik-Bronstein in 1951 and Botvinnik-Smyslov in 1954 – so Botvinnik retained the title both times. In 1956 FIDE introduced two apparently minor changes which Soviet grandmaster and chess official Yuri Averbakh alleged were instigated by the two Soviet representatives in FIDE, who were personal friends of reigning champion Mikhail Botvinnik. A defeated champion would have the right to a return match. FIDE also limited the number of players from the same country that could compete in the Candidates Tournament, on the grounds that it would reduce Soviet dominance of the tournament. Averbakh claimed that this was to Botvinnik's advantage as it reduced the number of Soviet players he might have to meet in the title match.[74] Botvinnik lost to Vasily Smyslov in 1957 but won the return match in 1958, and lost to Mikhail Tal in 1960 but won the return match in 1961. Thus Smyslov and Tal each held the world title for a year, but Botvinnik was world champion for rest of the time from 1948 to 1963. The return match clause was not in place for the 1963 cycle. Tigran Petrosian won the 1962 Candidates and then defeated Botvinnik in 1963 to become world champion.

FIDE system (1963–1975)

[edit]After the 1962 Candidates, Bobby Fischer publicly alleged that the Soviets had colluded to prevent any non-Soviet – specifically him – from winning. He claimed that Petrosian, Efim Geller and Paul Keres had prearranged to draw all their games, and that Viktor Korchnoi had been instructed to lose to them. Yuri Averbakh, who was head of the Soviet team, confirmed in 2002 that Petrosian, Geller and Keres arranged to draw all their games in order to save their energy for games against non-Soviet players.[74] Korchnoi, who defected from the USSR in 1976, never confirmed that he was forced to throw games. FIDE responded by changing the format of future Candidates Tournaments to eliminate the possibility of collusion. Beginning in the next cycle, 1963–1966, the round-robin tournament was replaced by a series of elimination matches. Initially the quarter-finals and semi-finals were best of 10 games, and the final was best of 12. Fischer, however, refused to take part in the 1966 cycle, and dropped out of the 1969 cycle after a controversy at 1967 Interzonal in Sousse.[75] Both these Candidates cycles were won by Boris Spassky, who lost the title match to Petrosian in 1966, but won and became world champion in 1969.[76][77]

In the 1969–1972 cycle Fischer caused two more crises. He refused to play in the 1969 US Championship, which was a Zonal Tournament. This would have eliminated him from the 1969–1972 cycle, but Benko was persuaded to concede his place in the Interzonal to Fischer.[78] FIDE President Max Euwe accepted this maneuver and interpreted the rules very flexibly to enable Fischer to play, as he thought it important for the health and reputation of the game that Fischer should have the opportunity to challenge for the title as soon as possible.[79] Fischer crushed all opposition and won the right to challenge reigning champion Boris Spassky.[76] After agreeing to play in Yugoslavia, Fischer raised a series of objections and Iceland was the final venue. Even then Fischer raised difficulties, mainly over money. It took a phone call from United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and a doubling of the prize money by financier Jim Slater to persuade him to play. After a few more traumatic moments Fischer won the match 12½–8½.[80][81]

An unbroken line of FIDE champions had thus been established from 1948 to 1972, with each champion gaining his title by beating the previous incumbent. This came to an end when Anatoly Karpov won the right to challenge Fischer in 1975. Fischer objected to the "best of 24 games" championship match format that had been used from 1951 onwards, claiming that it would encourage whoever got an early lead to play for draws. Instead he demanded that the match should be won by whoever first won 10 games, except that if the score reached 9–9 he should remain champion. He argued that this was more advantageous to the challenger than the champion's advantage under the existing system, where the champion retained the title if the match was tied at 12–12 including draws. Eventually FIDE deposed Fischer and crowned Karpov as the new champion.[82] Fischer privately maintained that he was still World Champion. He went into seclusion and did not play chess in public again until 1992, when Spassky agreed to participate in an unofficial rematch for the World Championship. Fischer won the 1992 Fischer–Spassky rematch decisively with a score of 10–5.

Karpov and Kasparov (1975–1993)

[edit]After becoming world champion by default, Karpov confirmed his worthiness for the title with a string of tournament successes from the mid 70s to the early 80s. He defended his title twice against ex-Soviet Viktor Korchnoi, first in Baguio in 1978 (6–5 with 21 draws) and in Merano in 1981 (6–2, with 10 draws). In the 1984 World Chess Championship, Karpov fought against Garry Kasparov. Karpov retained the title after the tournament went for more than five months and was terminated with Karpov leading with five wins to Kasparov's three and 40 draws after 48 matches.

Karpov eventually lost his title in 1985 to Kasparov, who won the title by a scoreline of 13–11. The two played three more subsequent championships in World Chess Championship 1986 (won by Kasparov, 12½–11½), World Chess Championship 1987 (drawn 12–12, Kasparov retained the title), and World Chess Championship 1990 (won by Kasparov, 12½–11½). In the five tournaments, Kasparov and Karpov played a total of 144 World Championship games with 104 draws, 21 wins by Kasparov and 19 wins by Karpov.[83]

Split title (1993–2006)

[edit]In 1993, Nigel Short broke the domination of Kasparov and Karpov by defeating Karpov in the candidates semi-finals followed by Jan Timman in the finals, thereby earning the right to challenge Kasparov for the title. However, before the match took place, both Kasparov and Short complained of FIDE's mishandling of the prize pool in organizing the match, corruption in the leadership, and FIDE's failure to abide by their own rules,[84][85] and split from FIDE to set up the Professional Chess Association (PCA), under whose auspices they held their match. In response, FIDE stripped Kasparov of his title and held a championship match between Karpov and Timman. For the first time in history, there were two World Chess Champions: Kasparov defeated Short and Karpov beat Timman.

FIDE and the PCA each held a championship cycle in 1993–1996, with many of the same challengers playing in both. Kasparov and Karpov both won their respective cycles. In the PCA cycle, Kasparov defeated Viswanathan Anand in the PCA World Chess Championship 1995. Karpov defeated Gata Kamsky in the final of the FIDE World Chess Championship 1996. Negotiations were held for a reunification match between Kasparov and Karpov in 1996–97,[86] but nothing came of them.[87]

Soon after the 1995 championship, the PCA folded, and Kasparov had no organisation to choose his next challenger. In 1998 he formed the World Chess Council, which organised a candidates match between Alexei Shirov and Vladimir Kramnik. Shirov won the match, but negotiations for a Kasparov–Shirov match broke down, and Shirov was subsequently omitted from negotiations, much to his disgust. Plans for a 1999 or 2000 Kasparov–Anand match also broke down, and Kasparov organised a match with Kramnik in late 2000. In a major upset, Kramnik won the match with two wins, thirteen draws, and no losses. At the time the championship was called the Braingames World Chess Championship, but Kramnik later referred to himself as the Classical World Chess Champion.

Meanwhile, FIDE had decided to scrap the Interzonal and Candidates system, instead having a large knockout event in which a large number of players contested short matches against each other over just a few weeks (see FIDE World Chess Championship 1998). Rapid and blitz games were used to resolve ties at the end of each round, a format which some felt did not necessarily recognize the highest-quality play: Kasparov refused to participate in these events, as did Kramnik after he won the Classical title in 2000. In the first of these events, in 1998, champion Karpov was seeded directly into the final, but he later had to qualify alongside the other players. Karpov defended his title in the first of these championships in 1998, but resigned his title in protest at the new rules in 1999. Alexander Khalifman won the FIDE World Championship in 1999, Anand in 2000, Ruslan Ponomariov in 2002, and Rustam Kasimdzhanov in 2004.

By 2002, not only were there two rival champions, but Kasparov's strong results – he had the top Elo rating in the world and had won a string of major tournaments after losing his title in 2000 – ensured even more confusion over who was World Champion. In May 2002, American grandmaster Yasser Seirawan led the organisation of the so-called "Prague Agreement" to reunite the world championship. Kramnik had organised a candidates tournament (won later in 2002 by Peter Leko) to choose his challenger. It was agreed that Kasparov would play the FIDE champion (Ponomariov) for the FIDE title, and the winner of that match would face the winner of the Kramnik–Leko match for the unified title. However, the matches proved difficult to finance and organise. The Kramnik–Leko match did not take place until late 2004 (it was drawn, so Kramnik retained his title).

Meanwhile, FIDE never managed to organise a Kasparov match, either with 2002 FIDE champion Ponomariov, or 2004 FIDE champion Kasimdzhanov. Kasparov's frustration at the situation played a part in his decision to retire from chess in 2005, still ranked No. 1 in the world. Soon after, FIDE dropped the short knockout format for a World Championship and announced the FIDE World Chess Championship 2005, a double round robin tournament to be held in San Luis, Argentina between eight of the leading players in the world. However Kramnik insisted that his title be decided in a match, and declined to participate. The tournament was convincingly won by the Bulgarian Veselin Topalov, and negotiations began for a Kramnik–Topalov match to unify the title.

Reunified title (since 2006)

[edit]Kramnik (2006–2007)

[edit]The World Chess Championship 2006 reunification match between Topalov and Kramnik was held in late 2006. After much controversy, it was won by Kramnik. Kramnik thus became the first unified and undisputed World Chess Champion since Kasparov split from FIDE to form the PCA in 1993. This match, and all subsequent championships, have been administered by FIDE.

Anand (2007–2013)

[edit]Kramnik played to defend his title at the World Chess Championship 2007 in Mexico. This was an 8-player double round robin tournament, the same format as was used for the FIDE World Chess Championship 2005. This tournament was won by Viswanathan Anand, thus making him the World Chess Champion. Because Anand's World Chess Champion title was won in a tournament rather than a match, a minority of commentators questioned the validity of his title.[88] Kramnik also made ambiguous comments about the value of Anand's title, but did not claim the title himself then.[89] (In a 2015 interview Kramnik dated the loss of his world championship title to his 2008 match against Anand rather than the 2007 tournament,[90] and he likewise did not contradict an interviewer who dated it thus in a 2019 interview.)[91] Subsequent world championship matches returned to the format of a match between the champion and a challenger.

The following two championships had special clauses arising from the 2006 unification. Kramnik was given the right to challenge for the title he lost in a tournament in the World Chess Championship 2008, which Anand won. Then Topalov, who as the loser of the 2006 match was excluded from the 2007 championship, was seeded directly into the Candidates final of the World Chess Championship 2010. He won the Candidates (against Gata Kamsky) to set up a match against Anand, who again won the championship match.[92][93] The next championship, the World Chess Championship 2012, had short knock-out matches for the Candidates Tournament. This format was not popular with everyone, and world No. 1 Magnus Carlsen withdrew in protest. Boris Gelfand won the Candidates. Anand won the championship match again, in tie breaking rapid games, for his fourth consecutive world championship win.[94]

Carlsen (2013–2023)

[edit]Since 2013, the Candidates Tournament has been an eight-player double round robin tournament, with the winner playing a match against the champion for the title. Norwegian Magnus Carlsen won the 2013 Candidates and then convincingly defeated Anand in the World Chess Championship 2013.[95][96]

Beginning with the 2014 Championship cycle, the World Championship has followed a 2-year cycle: qualification for the Candidates in the odd year, the Candidates tournament early in the even year, and the World Championship match later in the even year. This and the next two cycles resulted in Carlsen successfully defending his title: against Anand in 2014;[97] against Sergey Karjakin in 2016;[98] and against Fabiano Caruana in 2018. Both the 2016 and 2018 defences were decided by tie-break in rapid games.[99]

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the 2020 Candidates Tournament, and caused the next match to be postponed from 2020 to 2021.[100] Carlsen again successfully defended his title, defeating Ian Nepomniachtchi in the World Chess Championship 2021.

Ding (2023–present)

[edit]Soon after the 2021 match, Carlsen indicated that he would not defend the title again.[101] This was confirmed in an announcement by FIDE on 20 July 2022.[102] As a consequence, the top two finishers of the Candidates Tournament, Ian Nepomniachtchi and Ding Liren, played in the 2023 championship in Astana, Kazakhstan, from 7 April to 30 April 2023.[103] Ding won, making him the first World Chess Champion from China. FIDE referred to Ding as the "17th World Champion"; thus the "Classical" line of Champions during the split has been de facto legitimised over the FIDE line by FIDE itself.[104][105] The next world championship will be held in 2024, in which Ding will defend his title against the challenger Gukesh Dommaraju.

Format

[edit]Until 1948, world championship contests were arranged privately between the players. As a result, the players also had to arrange the funding, in the form of stakes provided by enthusiasts who wished to bet on one of the players. In the early 20th century this was sometimes an obstacle that prevented or delayed challenges for the title. Between 1888 and 1948 various difficulties that arose in match negotiations led players to try to define agreed rules for matches, including the frequency of matches, how much or how little say the champion had in the conditions for a title match and what the stakes and division of the purse should be. However these attempts were unsuccessful in practice, as the same issues continued to delay or prevent challenges. There was an attempt by an external organization to manage the world championship from 1887 to 1889, but this experiment was not repeated until 1948.

After the death of world champion Alexander Alekhine in 1946, the World Chess Championship 1948 was a one-off tournament to decide a new world champion.

Since 1948, the world championship has mainly operated on a two or three-year cycle, with four stages:

- Zonal tournaments: different regional tournaments to qualify for the following stage. Qualifiers from zonals play in the Interzonal (up to 1993), knockout world championship (1998 to 2004) or Chess World Cup (since 2005).

- Candidates qualification tournaments. From 1948 to 1993, the only such tournament was the Interzonal. Since 2005, the Interzonal has mainly been replaced by the Chess World Cup. However extra qualification events have also been added: the FIDE Grand Prix, a series of tournaments restricted to the top 20 or so players in the world; and the Grand Swiss tournament. Since 2023, the Grand Prix has been replaced by the FIDE Circuit, making many more tournaments (not only those organised by FIDE) contribute towards Candidates qualification. In addition, a small number of players sometimes qualify directly for the Candidates either by finishing highly in the previous cycle, on rating, or as a wild card.

- The Candidates Tournament is a tournament to choose the challenger. Over the years it has varied in size (between 8 and 16 players) and in format (a tournament, a set of matches, or a combination of the two). Since the 2013 cycle it has always been an eight-player, double round-robin tournament.

- The championship match between the champion and the challenger.

There have been a few exceptions to this system:

- In the 1957 and 1960 cycles, a rule existed which allowed the champion a rematch if he lost the championship match, leading to the 1958 and 1961 matches. There were also one-off rematches in 1986 and 2008.

- The 1975 world championship was not held, as the champion (Fischer) refused to defend his title; his challenger (Karpov) became champion by default.

- There were many variations during the world title split between 1993 and 2006. FIDE determined the championship by a single knockout tournament between 1998 and 2004, and by an eight-player tournament in 2005; meanwhile, the Classical world championship had no qualifying stages in 2000, and only a Candidates tournament in its 2004 cycle.

- A one-off match to reunite the world championship was held in 2006.

- The 2007 world championship was determined by an eight-player tournament instead of a match.

- The 2023 world championship was played between the top two finishers of the Candidates, as the champion (Carlsen) refused to defend his title.

World champions

[edit]Pre-FIDE world champions (1886–1946)

[edit]| # | Name | Country | Years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wilhelm Steinitz | 1886–1894 | ||

| 2 | Emanuel Lasker | 1894–1921 | ||

| 3 | José Raúl Capablanca | 1921–1927 | ||

| 4 | Alexander Alekhine | 1927–1935 | ||

| 5 | Max Euwe | 1935–1937 | ||

| (4) | Alexander Alekhine | 1937–1946 | ||

| Interregnum | ||||

FIDE world champions (1948–1993)

[edit]| # | Name | Country | Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Mikhail Botvinnik | 1948–1957 | |

| 7 | Vasily Smyslov | 1957–1958 | |

| (6) | Mikhail Botvinnik | 1958–1960 | |

| 8 | Mikhail Tal | 1960–1961 | |

| (6) | Mikhail Botvinnik | 1961–1963 | |

| 9 | Tigran Petrosian | 1963–1969 | |

| 10 | Boris Spassky | 1969–1972 | |

| 11 | Bobby Fischer | 1972–1975 | |

| 12 | Anatoly Karpov | 1975–1985 | |

| 13 | Garry Kasparov | 1985–1993 |

Classical (PCA/Braingames) world champions (1993–2006)

[edit]| # | Name | Country | Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | Garry Kasparov | 1993–2000 | |

| 14 | Vladimir Kramnik | 2000–2006 |

FIDE world champions (1993–2006)

[edit]| Name | Country | Years |

|---|---|---|

| Anatoly Karpov | 1993–1999 | |

| Alexander Khalifman | 1999–2000 | |

| Viswanathan Anand | 2000–2002 | |

| Ruslan Ponomariov | 2002–2004 | |

| Rustam Kasimdzhanov | 2004–2005 | |

| Veselin Topalov | 2005–2006 |

FIDE (reunified) world champions (2006–present)

[edit]| # | Name | Country | Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | Vladimir Kramnik | 2006–2007 | |

| 15 | Viswanathan Anand | 2007–2013 | |

| 16 | Magnus Carlsen | 2013–2023 | |

| 17 | Ding Liren | 2023–present |

World Champions by number of title match victories

[edit]The table below organises the world champions in order of championship wins. A successful defense counts as a win for the purposes of this table, even if the match is drawn. The table is made more complicated by the split between the "Classical" and FIDE world titles between 1993 and 2006. If total number of championship wins is identical, the number of wins at undisputed championships, the number of years as undisputed champion, the number of years as champion are used as tie-breakers (in that order). If all numbers are the same, the players are listed by year of first victory at world championships (in chronological order).

| Champion | Number of wins | Years as | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Undisputed | FIDE | Classical | Champion | Undisputed champion | |

| 6 | 6 | 27 | 27 | |||

| 6 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 8 | ||

| 6 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 10 | ||

| 5 | 5 | 13 | 13 | |||

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | |||

| 5 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 6 | ||

| 4 | 4 | 17 | 17 | |||

| 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | |||

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

Other world chess championships

[edit]Restricted events:

- Women's World Chess Championship

- World Junior Chess Championship (under 20 years of age)

- World Youth Chess Championship (lower age groups)

- World Senior Chess Championship

- World Amateur Chess Championship

Other time limits:

- World Rapid Chess Championship

- World Blitz Chess Championship

- World Correspondence Chess Championship

Teams:

Computer chess:

Chess Problems:

Chess variants:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Henshaw, Jack (9 December 2021). "World Chess Championship 2021: Decisively decided? • The Tulane Hullabaloo". The Tulane Hullabaloo. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ a b Hendriks, Willy (2020). "1. Footnotes to Greco; 2. The Nimzowitsch of the 17th century; 3. With a little help from the opponent". On the Origin of Good Moves: A Skeptic's Guide to Getting Better at Chess. New in Chess. ISBN 978-90-5691-879-8.

Most books on the history of chess make a leap of a century after Greco and go directly to the Frenchman François André Danican Philidor (1726-1795). Although a few things happened in-between, he was the next player considered to stand head and shoulders above his contemporaries. ... However, I do not know how well acquainted Philidor was with Greco's games. He didn't have a high opinion of them, because Greco 'achieved the win in his games often in a risky way and only thanks to mistakes made by the opponent, without ever drawing the attention of the reader to these errors on both sides.' But as we will shortly see, one might argue that Philidor himself was even more outstanding at this 'technique'.

- ^ a b Winter, Edward. "Early Uses of 'World Chess Champion'". Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ "A History of Chess", H. J. R. Murray, pp. 863–865

- ^ "A History of Chess", H. J. R. Murray, p. 870

- ^ Winter, Edward (22 September 2023). "Jeremy Silman (1954-2023)". chesshistory.com. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ a b "A History of Chess", H. J. R. Murray, p. 878: "It was, however, generally accepted that Deschapelles was the strongest player of his time, and Sarratt appears to have acquiesced in this opinion, although there was apparently no stronger reason for it than the fact that the general standard of French chess had been higher than that of English chess in the end of the eighteenth century. The result of Lewis's visit was to show that there was very little, if any, difference in strength between Deschapelles and himself."

- ^ David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, Oxford University Press, 1992 (2nd edition), p.56. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ a b "A History of Chess", H. J. R. Murray, pp. 882–5

- ^ Golombek, Harry (1976). A History of Chess. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. p. 126. ISBN 0-7100-8266-5.

- ^ Walker, George (1850). Chess and Chess-Players. London: C.J. Skeet. p. 381.

- ^ David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, Oxford University Press, 1992 (2nd edition), p.390. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ F. M. Edge, The exploits and triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, 1859 page 115

- ^ Walker, George (1850). Chess and Chess-Players. Charles J. Skeet. p. 38.

- ^ a b Jeremy P. Spinrad. "Early World Rankings" (PDF). Chess Cafe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ G.W. (July–December 1840). "The Café de la Régence". Fraser's Magazine. 22. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008. Jeremy Spinrad believes the author was George Walker.

- ^ Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of Revolution Archived 12 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Paul Metzner, Berkeley: University of California Press, c. 1998.

- ^ "From Morphy to Fischer", Israel Horowitz, (Batsford, 1973) p.3

- ^ David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, Oxford University Press, 1992 (2nd edition), p.44. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ The Earl of Mexborough's speech to the meeting of Yorkshire Chess Clubs, as reported in the 1845 Chess Player's Chronicle (with the cover date 1846) – Winter, Edward. "Early Uses of 'World Chess Champion'". Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ a b David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, Oxford University Press, 1992 (2nd edition), p.15. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ a b "From Morphy to Fischer", Israel Horowitz, (Batsford, 1973) p.4

- ^ David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, Oxford University Press, 1992 (2nd edition), p.263. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ Section "Progress of Chess" in Henry Edward Bird (2004) [1893]. Chess History And Reminiscences. Kessinger. ISBN 1-4191-1280-5. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ Staunton, Howard (April 2003). The Chess Tournament. Hardinge Simpole. ISBN 1-84382-089-7. This can be viewed online at or downloaded as PDF from Staunton, Howard (1852). Google books: The Chess Tournament. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ a b David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, Oxford University Press, 1992 (2nd edition), pp.216–217. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ Bell's Life in London, 24 February 1856, p. 5

- ^ 1858–59 Paul Morphy Matches Archived 25 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Mark Weeks' Chess Pages

- ^ "I grandi matches 1850–1864". Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Early Uses of 'World Chess Champion' Archived 13 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Edward G. Winter, 2007

- ^ Doazan, Gabriel-Éloy (1859). Labourdonnais – Morphy (PDF). p. 4.

Après Deschapelles et Labourdonnais, il m'a été donné de voir un jeune homme que l'on peut et que l'on doit placer sur la même ligne. Sa supériorité est aussi évidente que la leur. Elle est aussi incontestable et se révèle de la même manière.

- ^ David Lawson. "Paul Morphy: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess". Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d "From Morphy to Fischer", Israel Horowitz, (Batsford, 1973) p.16

- ^ Kaufman, Larry (4 September 2023). "Accuracy, Ratings, and GOATs". Chess.com. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ Kasparov, Garry (2003). My Great Predecessors, Vol. I. Everyman Chess. p. 55. ISBN 1857443306.

- ^ Kasparov, Garry (2003). My Great Predecessors, Vol. I. Everyman Chess. p. 31. ISBN 1857443306.

- ^ Kasparov, Garry (2003). My Great Predecessors, Vol. I. Everyman Chess. p. 59. ISBN 1857443306.

- ^ 1883 London Tournament Archived 13 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Mark Weeks' Chess Pages

- ^ a b David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess, Oxford University Press, 1992 (2nd edition), p.459. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ "The Centenary Match, Kasparov–Karpov III", Raymond Keene and David Goodman, Batsford 1986, p.9

- ^ J.I. Minchin, the editor of the tournament book, wrote, "Dr. Zukertort at present holds the honoured post of champion, but only a match can settle the position of these rival monarchs of the Chess realm." J.I. Minchin (editor), Games Played in the London International Chess Tournament, 1883, British Chess Magazine, 1973 (reprint), p.100.

- ^ "From Morphy to Fischer", Israel Horowitz, (Batsford, 1973), p.24

- ^ Keene, Raymond; Goodman, David (1986). The Centenary Match, Kasparov–Karpov III. Collier Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-02-028700-3.

- ^ a b "Ready for a big chess match" (PDF). The New York Times. 11 March 1894. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Fine, R. (1952). The World's Great Chess Games. André Deutsch (now as paperback from Dover).

- ^ Weeks, Mark. "World Chess Champions". Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ Silman, J. "Wilhelm Steinitz". Archived from the original on 17 April 2012.

- ^ "Wilhelm Steinitz". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ "Do You Know The World Chess Champions?". Rafael Leitão. 19 December 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Thulin, A. (August 2007). "Steinitz—Chigorin, Havana 1899 – A World Championship Match or Not?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008. Based on Landsberger, K. (2002). The Steinitz Papers: Letters and Documents of the First World Chess Champion. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1193-7. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "New York 1889 and 1924". Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ "I matches 1880/99". Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ a b "From Morphy to Fischer", Israel Horowitz, (Batsford, 1973) 39

- ^ a b c "1921 World Chess Championship". Archived from the original on 20 January 2005. Retrieved 4 June 2008. This cites: a report of Lasker's concerns about the location and duration of the match, in "Emanuel Lasker column". New York Evening Post. 15 March 1911.; Capablanca's letter of 20 December 1911 to Lasker, stating his objections to Lasker's proposal; Lasker's letter to Capablanca, breaking off negotiations; Lasker's letter of 27 April 1921 to Alberto Ponce of the Havana Chess Club, proposing to resign the 1921 match; and Ponce's reply, accepting the resignation.

- ^ a b c d e f Winter, Edward. "How Capablanca Became World Champion". Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ Clayton, G. "The Mad Aussie's Chess Trivia – Archive No. 3". Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ^ a b Winter, E. "Capablanca v Alekhine, 1927". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2008. Regarding a possible "two-game lead" clause, Winter cites Capablanca's messages to Julius Finn and Norbert Lederer dated 15 October 1927, in which he proposed that, if the Buenos Aires match were drawn, the second match could be limited to 20 games. Winter cites La Prensa 30 November 1927 for Alekhine's conditions for a return match.

- ^ a b "Jose Raul Capablanca: Online Chess Tribute". chessmaniac.com. 28 June 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ "From the Editorial Chair". Lasker's Chess Magazine. 1. January 1905. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ a b Section "Stakes at Chess" in Henry Edward Bird (2004) [1893]. Chess History And Reminiscences. Kessinger. ISBN 1-4191-1280-5. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ "Lasker biography". Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

- ^ Horowitz, I.A. (1973). From Morphy to Fischer. Batsford.

- ^ Wilson, F. (1975). Classical Chess Matches, 1907–1913. Dover. ISBN 0-486-23145-3. Archived from the original on 20 January 2005. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ "New York 1924". chessgames. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ a b Wall. "FIDE History". Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ^ "FIDE History". FIDE. Archived from the original on 14 November 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ^ Seirawan, Y. (August 1998). "Whose Title Is it, Anyway?". GAMES Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ^ Winter, E. "Chess Notes Archive [17]". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2008. Winter cites: Resolution XI of the 1926 FIDE Congress, regarding the "London Rules"; page 5 of the 1926 Congress' minutes about the initial decision to set up an "official championship of FIDE"; Schweizerische Schachzeitung (September 1927) for FIDE's decision to await the result of the Capablanca–Alekhine match; the minutes of FIDE's 1928 congress for the adoption of the forthcoming 1928 Bologjubow–Euwe match as being for the "FIDE championship" and its congratulations to the winner, Bologjubow; the minutes of FIDE's 1928 congress for Alekhine's agreement and his exception for Capablanca; a resolution of 1928 for the attempt to arrange an Alekhine-Bogoljubow match; subsequent FIDE minutes for the non-occurrence of the match (under FIDE); and the vanishing of the title "Champion of FIDE".

- ^ Winter, E. "World Championship Disorder". Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ^ a b c d Winter, E. (2003–2004). "Interregnum". Chess History Center. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ^ Weeks, M. "World Chess Championship FIDE Events 1948–1990". Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2008.

- ^ "Index of FIDE Events 1948–1990 : World Chess Championship". www.mark-weeks.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Wade, R. G. (1964). The World Chess Championship 1963. Arco. LCCN 64514341.

- ^ a b Kingston, T. (2002). "Yuri Averbakh: An Interview with History – Part 2" (PDF). The Chess Cafe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Wade, R.; O'Connell, K. (1972). The Games of Robert J. Fischer. Batsford. pp. 331–46.

- ^ a b Weeks, M. "Index of FIDE Events 1948–1990 : World Chess Championship". Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Weeks, M. "FIDE World Chess Championship 1948–1990". Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Donlan, M. "Ed Edmondson Letter" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Sosonko, Gennadi (2001). "Remembering Max Euwe Part 1" (PDF). The Chess Cafe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ "Fischer, outspoken ex-chess champion, dies of kidney failure". ESPN. 19 January 2008. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Weeks, M. "World Chess Championship 1972 Fischer – Spassky Title Match:Highlights". Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Weeks, M. "World Chess Championship 1975: Fischer forfeits to Karpov". Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ "The chess games of Garry Kasparov". Chessgames.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Battle off the boards hots up". The Indian Express. p. 19. Archived from the original on 28 February 1993. Retrieved 4 June 2024. Alt URL

- ^ Lundstrom, Harold (23 July 1993). "Many Fans Root For Rebels In Fight With Chess Federation". The Deseret News. p. 12. Archived from the original on 23 July 1993. Retrieved 4 June 2024. Alt URL

- ^ The Week in Chess 127 Archived 10 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 14 April 1997

- ^ Kasparov Interview Archived 6 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Week in Chess 206, 19 October 1998

- ^ Topalov Kramnik 2006, book review by Jeremy Silman Archived 12 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Interview with Kramnik Archived 3 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 10 July 2008

- ^ McGourty, Colin (26 June 2015). "Vladimir Kramnik: "It turns out I'm 52, not 40!"". chess24.com. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

Most likely I finally felt liberated after losing the World Championship title in 2008.

- ^ Cox, David (18 July 2019). "Vladimir Kramnik Interview: 'I'm Not Afraid To Lose'". chess.com. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

Your reign as champion ended with the 2008 defeat to Vishy Anand.

- ^ Regulations for the 2007 – 2009 World Chess Championship Cycle Archived 10 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, sections 4 and 5, FIDE online. Undated, but reported in Chessbase on 24 June 2007 Archived 21 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sofia R7: Topalov beats Kamsky, wins candidates match | Chess News". Chessbase.com. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "FIDE World Chess Championship Match – Anand Retains the Title!". Fide.com. 20 April 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Magnus Carlsen wins FIDE Candidates' Tournament". Fide.com. 1 April 2013. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "World Championship Match – PRESS RELEASE". Fide.com. 7 May 2013. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Sochi G11: In dramatic finale, Carlsen retains title". ChessBase. 23 November 2014. Archived from the original on 30 November 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "The World Chess Championship comes to New York City 11—30 November 2016 | World Chess". Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Mather, Victor (28 November 2018). "Magnus Carlsen Beats Fabiano Caruana to win the World Chess Championship". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Arkady Dvorkovich: The match for the chess crown will be postponed to 2021 Archived 1 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, FIDE, 30 June 2020

- ^ BREAKING: Carlsen Might Only Defend Title Vs. Firouzja Archived 14 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Peter Doggers, chess.com, 21 December 2021

- ^ "Statement by FIDE President on Magnus Carlsen's announcement". FIDE. 20 July 2022. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Victor Mather (20 July 2022). "Lacking Motivation, Magnus Carlsen Will Give Up World Chess Title". New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Dinic, Milan (30 April 2023). "Ding Liren makes history, becoming World Champion". worldchampionship.fide.com. FIDE. Archived from the original on 24 August 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

Ding Liren made history by becoming the 17th World Champion in chess, defeating Ian Nepomniachtchi in the final game of the tiebreaks

- ^ Keene, Raymond (13 May 2023). "Shalom Alekhine: Ding joins the chess greats". The Article. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

It's reassuring to see that even FIDÉ now subscribes to the canonical view of who has and who has not been world champion. By openly conceding that the Chinese Grandmaster Ding Liren is the 17th champion, FIDÉ have confirmed that the true line of succession is Kasparov (13th champion), Kramnik (14), Anand (15), Carlsen (16) and now Ding Liren (17).

External links

[edit]- Mark Weeks' pages on the championships – Contains all results and games

- Graeme Cree's World Chess Championship Page (archived) – Contains the results, and also some commentary by an amateur chess historian

- Kramnik Interview: From Steinitz to Kasparov – Vladimir Kramnik (the 14th World Chess Champion) shares his views on the first 13 World Chess Champions.

- Chessgames guide to the World Championship

- The World Chess Championship by Edward Winter